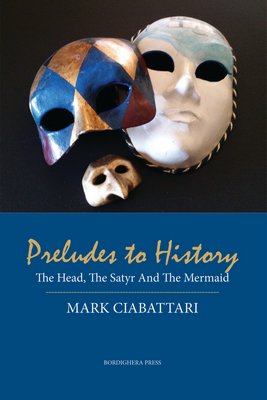

In Mark Ciabattari’s new book, “Preludes to History,” (Bordighera Press, $14, 124 pp, Paper) you will discover a disembodied talking head, a satyr, and a mermaid in the bathtub. Welcome to his world. He has been compared to Italo Calvino, Luigi Pirandello, Franz Kafka, Philip K. Dick, Kurt Vonnegut, Jorge Luis Borges, Samuel Beckett and Woody Allen.

Mr. Ciabattari was for many years a fixture in the intellectual world of the East End. His lectures at the Rogers Memorial and John Jermain Memorial libraries always drew capacity crowds. He has a Ph.D. in American intellectual and cultural history from New York University. But a semester at Stanford University’s campus in Florence, Italy, allowed him to immerse himself in the absurdist movement in European literature, something with which he has a definite affinity. He has taught at NYU, Mercy College, Yeshiva University, and various City University of New York campuses.

Previous books include “Clay Creatures,” which pairs a story by Mr. Ciabattari with one by Luigi Pirandello. It would be difficult to tell who wrote which if the author identification was stripped from the text. It has been commented on, by me, in a Southampton Press review, “It took whatever is the Italian word for chutzpah to pull it off.” But pull it off he did. Other books include “Dreams of an Imaginary New Yorker Named Rizzoli” and “The Literal Truth: Rizzoli Dreams of Eating the Apple of Earthly Delights.”

“Preludes to History” is the third book about Rizzoli, Mr. Ciabattari’s alter-ego. Actually, the first story in “Preludes to History” features Rizzoli’s ancestor, Vico Rizzoli. The story, “The Head,” takes place in Italy in 1938. Rizzoli arrives in Rome from the provinces looking for a job. He is hired as a janitor in the Criminology Museum in Rome. (There is, in fact, such a museum in Rome.) Rizzoli works at night, so he never encounters any patrons. He sleeps in a basement room. His dinner appears mysteriously every day and he never knows who has delivered it. He spends his night shift sweeping and polishing and gazing at all the exhibits.

Then, one day he leans against a panel which gives way. It reveals another room of which he was unaware. The room contains nothing but what appears to be a fish bowl containing a human head, with wires and tubes protruding from it. The head was that of Giovanni Passannante, the Italian anarchist who had attempted to murder King Umberto I of Savoy in 1878. It had been preserved for study in formaldehyde by Cesare Lombroso, the Italian criminologist, who believed that criminals are inherently so, the products of their physiology; the result of nature, not nurture. Except for the wires and tubes, this much is relatively true.

But Rizzoli, a clever fellow with a knack for fixing things, configures the wires in such a way that the head is able to talk. The head also assumes another personality and name and is able, not only to talk about history, but to see the future. Rizzoli develops a great fondness for this head.

This is not the only wonder in the museum. It has a coffee bar where people can mingle and say whatever they like. When they leave, no one will remember what they have said or heard. Rizzoli can because a mysterious force does not allow him to leave the bar. Mr. Ciabattari gives emphasis to the dreamlike nature of his fiction with his inscription, quoting James Joyce, “History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.”

The second story, “The Mirror of Antiquity,” introduces us to the contemporary Rizzoli. He doesn’t, however, have a contemporary problem. He is visited by a satyr. The half-goat and half-man first appears as a hologram, then takes on a more solid shape. The satyr does what satyr’s are known to do. He is rough, but uses Rizzoli to teach him the art of foreplay. He is a shape-shifter. He can make Rizzoli invisible. He can inhabit Rizzoli’s body. He is able to take Rizzoli’s various body parts, his nose and mouth for instance, and send them on their way to practice what he has learned. I will tell no more.

In the final story, “Water Seeks Its Own Level,” Rizzoli comes home to find a mermaid in his bathtub. Some guys get all the luck. She wants him to help her propagate a new species.

Of course, some of this is broadly comic. Some of it is profoundly unsettling. The world of dreams and the world as we know it interpenetrate. It is often difficult to know which is which. There is a deep strain of ambiguity in what we think we know.

These are wonderful and endlessly fascinating stories. I guarantee that you will never forget them.