Edward Albee, who died Friday at his home in Montauk at age 88, could have been considered fourth in a list of “greatest living American playwrights.” He was like Eugene O’Neill, the writer whom most consider the first to wear that crown in modern theater, in that he had a dramatically successful and much more satisfying second act to his career.Mr. O’Neill had enjoyed critical and commercial success early on, in the 1920s, with Broadway productions, but it was the late plays, particularly “The Iceman Cometh,” “A Moon for the Misbegotten” and “Long Day’s Journey Into Night,” that put him at the top of the pantheon of American playwrights. Yet by the time of his death, in 1953, Mr. O’Neill had been supplanted by Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller, the Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams of the theater, both vying for the “greatest living” mantle.

Then came Mr. Albee—anticipating the absurdity, confusion, humor, and personal isolation of the 1960s.

Unlike many writers who emerge from childhood trauma to create art from the experience, Mr. Albee, born in Virginia, was adopted by a wealthy Larchmont, New York, couple, Reid and Frances Albee, and grew up attending some of the best schools in New York and Connecticut, though a rebellious personality resulted in him dropping out of some of them.

At 20, Mr. Albee began to live in New York City, and while supporting himself there he tried his hand at playwriting. It was in Berlin, though, where he first attracted attention when the one-act “The Zoo Story” opened there in 1959 on a double bill with a Samuel Beckett play. The following year, when the play was produced at the Provincetown Playhouse in Manhattan—perhaps not coincidentally, the Provincetown Players had nurtured the young Mr. O’Neill in the 1910s—it was seen as an inspiration for the nascent Off-Broadway movement. Three one-acts soon followed: “The Sandbox,” “The American Dream” and “The Death of Bessie Smith.”

Still, “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” was something of a creative and commercial explosion when it opened on Broadway in 1962. The raw emotions—particularly bitterness, rage and regret—of its characters, led by George and Martha, both “enthralled and shocked theatergoers,” wrote The New York Times. It received the Tony Award for Best Play, but the more conservative Pulitzer Prize judges refused to give a Drama Award at all that year.

Some critics were simply appalled, with one of the more trenchant comments given by the Daily News: “Three and a half hours long, four characters wide and a cesspool deep.”

Mike Nichols, making his film directing debut, helmed the big-screen version, with Elizabeth Taylor’s portrayal of Martha earning her a second Oscar.

Mr. Albee did win a Pulitzer Prize, his first of three, for his next major Broadway play, “A Delicate Balance,” about a wealthy couple overcome by past actions and present fears. The second Pulitzer came in 1975 for “Seascape,” which featured in its cast two talking lizards. This 15-year run of critical and commercial success—the film version of “Balance” starred Katharine Hepburn and Paul Schofield—allowed Mr. Albee to ascend to the top of the scaffold of American playwrights.

By this time, he was living part-time in Montauk and had established the Edward Albee Foundation. It has operated to the present day a series of annual residencies in Montauk for aspiring writers and other artists.

Mr. Albee had also begun a committed relationship with Jonathan Thomas, which would last until the latter’s death in 2005.

Though he did not make a point to be much in the public eye, Mr. Albee was by no means a reclusive writer while in residence in Montauk. He made appearances and participated in readings at Guild Hall, LongHouse Reserve, and other East Hampton venues, and in 1991 he received Guild Hall’s Lifetime Achievement Award in Literature.

After 1975, Mr. Albee continued to write steadily, but his plays were less well-received. For almost 20 years, he was beset by bad reviews and abuse of alcohol, and it seemed he had ceded the “greatest living American playwright” crown to Sam Shepard, Lanford Wilson, August Wilson and/or Tony Kushner. “The Lady from Dubuque” opened in 1980 and lasted just 12 performances, and “The Man Who Had Three Arms,” produced three years later, wound up having more arms than weeks on stage. Increasingly for Mr. Albee, Montauk became a safe haven as well as a retreat.

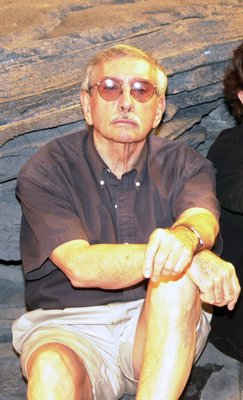

It was during this time, in the late 1980s, that this writer visited Mr. Albee at his oceanfront home. I found a cautious but gracious man who did not condescend to a clearly awestruck writer. His sardonic wit was on full display during an interview that lasted more than two hours and included a tour of the house and grounds off Old Montauk Highway.

It was obvious, however, that Albee had been stung by the critical roasting of recent years, and was at times wistful. In a comment he would echo in a 1991 New York Times interview, he said: “I suppose I could have gone on writing ‘Son of Virginia Woolf’ forever. But I never believed my own publicity. The mistake was thinking I was a Broadway playwright. I am a playwright, and for a while, Broadway was receptive.” He also said, “If Attila the Hun were alive today, he’d be a theater critic.”

Apparently, such defiance reinvigorated his writing. Like Mr. O’Neill, who also bounced back from alcohol struggles and mined his autobiography to resuscitate his stage career, Mr. Albee would command center stage again. The turning point was “Three Tall Women,” which would go on to earn him his third Pulitzer. The play was first produced in 1991 in Vienna, directed by Mr. Albee himself, and made its New York debut three years later. The story is about the three women who raised a boy to adulthood, and Mr. Albee was quoted as saying the work was “an exorcism.” A play produced a decade later, “The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia?” won a Tony Award, when Mr. Albee was in his mid-70s.

Five years ago, during an interview at the Arena Stage in Washington, D.C., Mr. Albee described something like an epiphany after finishing a draft of “The Zoo Story” that put him on the path to playwriting as his life’s obsession as well as occupation: “For the first time in my life when I wrote that play, I realized I had written something that wasn’t bad. ‘You know, Edward, this is pretty good. This is talented. Maybe you’re a playwright.’ So I thought, ‘Let’s find out what happens.’”

What happened was a great writing career, which ended Friday, September 16, in Montauk.