Three long strides down the airstairs off Pam Am Flight 101, George Harrison glanced back at John Lennon, for just a moment, in utter disbelief.

Lennon didn’t notice. He was transfixed by more than 4,000 screaming fans corralled into terraces overlooking the John F. Kennedy Airport tarmac in Queens, holding signs that read “Welcome Beatles!” and “Beatles, Unfair to Bald Men,” among others.

Flipping a cap over his voluminous hair, Lennon waved to the masses, as Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr popped out of the plane behind him.

The cries of the frenzied crowd crescendoed.

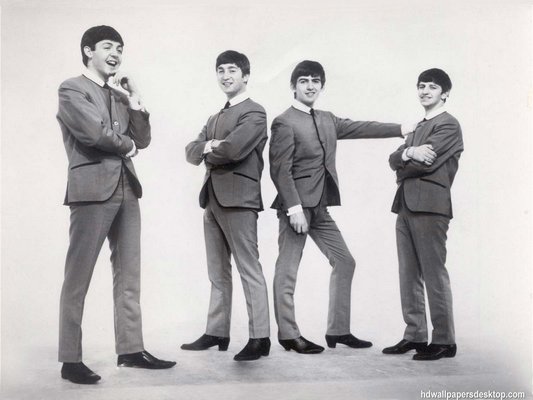

It was February 7, 1964. Almost 50 years ago to the day, the Beatles landed on American soil from Liverpool, England. They were clad in matching black suits and skinny ties. Their mop-tops and a cheeky swagger made girls want them and boys want to be them.

Two days later, 40 percent of the country would gather around their televisions to watch the Fab Four make their U.S. debut on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” The band would go on to release more than 20 studio albums, set a Billboard record—yet to be broken—and capture the hearts of millions worldwide, changing the face of music forever.

No one saw it coming, least of all them. During a press conference at the airport—after discussing Beethoven, social rebellion, their haircuts and “Liverpudlian” accents—the final question turned to business.

“Have you decided when you’re going to retire?” a reporter asked.

“Next week,” Lennon said.

“No,” McCartney said.

“No, we don’t know,” Lennon said.

“We’re going to keep going as long as we can,” Starr said.

“When we get fed up with it, you know,” Harrison said. “We’re still enjoying it.”

“Any minute now,” Starr deadpanned.

“After you make so much money, and then ...” another reporter suggested.

“No,” the Beatles said in unison.

“No, as long as we enjoy it, we’ll do it,” Harrison added. “Cuz we enjoyed it before we made any money.”

Just before the Beatles were whisked away into limousines bound for the Plaza Hotel, they had eight final words for the 200 members of the American press: their names.

They were still unknown as individuals.

In unison, and into their microphones, they chanted, “Paul, Ringo, George, John! Paul, Ringo, George, John!”

Half a century later, though two of them have died, their legacy lives on.

It all began in March 1957 with 16-year-old guitarist John Lennon and his skiffle group of friends, the Quarrymen, from the Quarry Bank School in the United Kingdom. Not long into their young careers, 15-year-old Paul McCartney joined on rhythm guitar. In February 1958, he invited his friend, 14-year-old George Harrison, to watch the band and audition.

At first, Lennon wasn’t sold. The founder thought Harrison was too young, but after impressing him, and a month of persistence, he enlisted the teen as the band’s lead guitarist. Over the years, a number of the members dropped out, including Stuart Sutcliffe, the original bassist who is often referred to as “the fifth Beatle,” and drummer Pete Best, who was replaced by Ringo Starr in 1962. The 22-year-old joined the band of multi-instrumentalists and ingenious songwriters now known as the Beatles—one that was already gaining traction across Britain.

They didn’t come to America out of nowhere, explained historian Joe Lauro, who will screen his film, “Legends: The Beatles,” during a three-day event from Friday, February 7, through Sunday, February 9, celebrating the Fab Four billed “It Was 50 Years Ago Today” at Bay Street Theatre in Sag Harbor. By the early 1960s, the Beatles phenomenon had already gained traction in England after manager Brian Epstein discovered the group in November 1961.

He was instantly impressed. But London’s major recording companies were not.

Nearly all of them had rejected the Beatles when Mr. Epstein secured a meeting with George Martin, head of EMI’s Parlophone label. In May 1962, he signed them, thanks to Mr. Epstein’s assurance that the young men would become international superstars.

Mr. Epstein was right, but not initially. The Beatles’ earliest efforts were far from promising. On September 16, 1963, the single “She Loves You” dropped in America. It didn’t even make the Billboard Chart. But when Time magazine recognized the band, variety show host Ed Sullivan booked them for at least three performances the following year.

That confidence from Sullivan fueled Mr. Epstein’s fire, giving him what he needed to persuade Capitol Records—the American arm of EMI—to risk $40,000, or an equivalent $250,000 today, on the Beatles’ newest single, “I Want to Hold Your Hand.”

In two weeks, it sold 1 million copies. By January 17, 1964, it was the number-one record in America. And when the Beatles touched down in Queens less than a month later, they arrived with a huge splash—much to their surprise.

“The Beatles knew that the record was doing well in America, but when they got off the plane, they had no idea,” Mr. Lauro said last week during a telephone interview. “They were completely flabbergasted by what they saw.”

According to some, the Beatles were exactly what the country sorely needed. They arrived just 77 days after President John F. Kennedy was assassinated.

“We were at our lowest,” Mr. Lauro said. “It was a bit of optimism and a diversion. It was a really big moment in America. It so profoundly affected so many young musicians, like myself, and it just gave the world music that will not die.”

Two days after the Beatles landed, they made their American debut in front of 73 million viewers on “The Ed Sullivan Show,” sparking an intense fan frenzy coined “Beatlemania!” during the early years of their success. With their talent, charm and energy, the public dialogue shifted away from mourning and toward entertainment.

After the performance, they were back in England by February 22, not to return to American soil until August. In just a few weeks, they had become legends. During the week of April 4, 1964, the Beatles held the first five slots on the Billboard Singles chart—a feat that has never been repeated.

“Nobody had that kind of long hair or dressed like that. It was terrific,” explained Steven Gaines, who co-authored “The Love You Make: An Insiders Story of the Beatles” with Peter Brown. “And they had the goods to back it up.”

While the older generation groaned at the high-energy rock and roll, the girls swooned—imagining themselves arm-in-arm with their favorite Beatle—and the boys decided they could play and sing, too.

Or, in Mr. Lauro’s case, they made believe they could—at least before trading in their “air-guitar” tennis racquets for real instruments and amps.

“I always wanted to be Paul,” he laughed. “My friends and I, across the street, had a little band. I’ll never forget the day ‘The White Album’ came out. We listened to that thing like it was the ‘Holy Grail.’ We just couldn’t believe it. We couldn’t believe how good it was. Through the notes, they could bring the emotions of people out. It’s not something anybody can do. It’s a skill to put the notes in a certain place that make someone’s heart want to cry.”

They listened to the songs over and over again on his older sister’s stereo, which was the best in the house. She was the definition of a “true, first-generation, American, Beatlemania fan,” he said.

And she wasn’t alone. Carol Ellis was also one of those girls. Every time a Beatles song came on the radio, she would be on the telephone with one of her similarly obsessed friends, tying up the line for hours. That drove the young girl’s mother crazy, she said, considering the Fab Four were monopolizing the airwaves.

“It was such a wonderful time of life,” the Hampton Bays resident wrote last week in an email. “I was 12 years old and thoroughly in love with the four mopped-hair musicians, Paul being my favorite. I would revolve my days around the Beatles for the next couple of years.”

McCartney, who owns a home in Amagansett, was a favorite among many of the band’s fangirls, including Christina Strassfield, now the museum director of Guild Hall in East Hampton. When he married Linda Eastman in 1969, the young girl would say, “I’m going to be Paul’s fifth wife.”

She regularly wore a red Beatles hat, while her older sister, Paula, got one in white and the eldest sister, Maria, had one in black. She was too young to own a pair of matching white Beatles boots, but her sisters did bring her with them to the local movie house in the Bronx to see the Beatles movies. And watch the girls in the audience kiss the screen.

“My sons got me a copy of the movie ‘Help!’ out of the library for me to watch about two years ago,” Ms. Strassfield wrote last week in an email. “They sat and watched it with me and said they had not seen me smile so much while watching anything.”

Then there was the famous Shea Stadium concert on August 15, 1965. The two opening bands had wrapped their sets. The Beatles were running an hour late. And their screaming 55,600 fans—the largest Beatles concert up to that time—were getting antsy.

The madness was building.

As the deafening din climbed, 16-year-old Joe Delia, who now calls Montauk home, happened to eye the scoreboard. And to his shock, it was noting the presence of his band, The Brothers, courtesy of manager Sid Bernstein, who was also promoting the Beatles concert and had invited his newly signed group to sit close to the stage as his guests.

He couldn’t believe his eyes.

“I remember it so clearly,” Mr. Delia said last week during a telephone interview. “And I remember girls came screaming at me. They must have been bored, waiting for this show, because they flocked around us. And then they went back to screaming for the Beatles. Standing on their seats screaming. And I mean everybody. It was not just 14-year-old girls. It was everybody. You could not help it.”

Bridgehampton resident Tracy Boyd’s section—a good distance from stage, which sat over second base—was a bit calmer, she recalled last week during a telephone interview. But when the Fab Four finally ran onto the field, the entire stadium erupted.

“People cheered and screamed so loudly, in fact, that it was absolutely impossible to hear your own voice, let alone anybody singing,” Ms. Boyd said. “There was just this mad, wild, unparalleled hysteria and it was wonderful.”

Hundreds of police officers gently handled the crowd, catching fainting girls and pushing back ambitious boys. One did slip through the ranks, Ms. Boyd recalled, sprinting across infield to the stage, where he dropped a bouquet of flowers.

For that, he earned a bow from John Lennon.

“There was that camaraderie,” she said. “Where everyone was of the same mind. It was an amazing thing.”

Ms. Ellis was watching the Beatles from a box seat, awestruck and exhilarated, when she decided she wasn’t close enough. She waited for her moment—a surge toward the stage—and wiggled her way right under the police officers’ arms, stretched out to hold back the crowd, and into a nearby dugout.

“Everyone else, including my cousins and aunt, were pushed back,” she said. “It was great, as no one was in front of my viewing ... [I was] jumping up and down, waving. Of course, in my 13-year-old mind, I was sure if the Beatles saw me, they would remember me.”

She was one in a sea of thousands. After the Beatles closed the night with “I’m Down”—which Mr. Delia will perform at Bay Street Theatre on Saturday, February 8, a night that will feature a number of local musicians covering Beatles songs—the concert-goers flooded out of the stadium and, some, right onto the Manhattan-bound trains.

“We were like hundreds of sardines packed into these hot subway cars,” Ms. Boyd said, “and everybody was singing the same Beatles songs. The trains were literally rocking, back and forth on the tracks, all the way back to Manhattan because everybody was moving in rhythm to the song. Everybody knew the words, everybody knew every note. And it was just one voice singing all the way home. It was a very special time. You don’t ever forget things like that.”

As quickly as the Beatles settled into stardom, they were over.

In 1966, the group ceased touring. The next year, Mr. Epstein died, leaving the Beatles without a unifying core. The members become personally involved in financial and legal conflicts, not to mention feuding over differing visions for the band.

It was reported that McCartney had assumed a patronizing, leadership role. Harrison refused to hide his frustration and resentment. Starr was pursuing other artistic interests. And Lennon became infatuated with Japanese-American conceptual artist Yoko Ono. They were inseparable, even in the studio, which violated a previous pact between the members to not let in wives or girlfriends.

By 1970, all four members had begun working on solo projects—the only one to incorporate every ex-Beatle was Starr—and, due to tension and plain animosity, it soon became clear that they needed to part ways.

But even though the band was in shambles, some say that they still ended on a high note.

“No one could have suspected that they would become such an enormous cultural influence and change the entire arena of the musical business,” Mr. Gaines said. “It’s pretty remarkable what they did in just 10 years. It was an important, positive influence on culture and society like no other entertainment group had been. There has never been anything like them ever again.”

In December 1980, the group unexpectedly reunited. Unfortunately, it was tragedy that brought them back together. They were one Beatle short. Lennon had been assassinated.

“Oh, it was horrible,” Ms. Boyd recalled. “It was unimaginable. People went into mourning for weeks. It’s still unimaginable to me, it really and truly is. I can hardly talk about it.”

Harrison died from metastatic lung cancer in November 2001. McCartney and Starr were among the performers who appeared at the Concert for George, and when musicians gathered at Radio City Music Hall in 2010 for Starr’s 70th birthday, though McCartney was a surprise.

Last month, the duo collaborated again at the 2014 Grammy Awards, in anticipation of “The Night That Changed America: A Grammy Salute to The Beatles,” which will air on Sunday, February 9—exactly 50 years after the band’s debut on “The Ed Sullivan Show.”

“I don’t think the Beatles filled some kind of hole. I think they ignited on their own,” Mr. Gaines said. “Some reporter asked Brian Epstein what the next big thing was, and Brian Epstein said, ‘The next big thing is a great tune.’”

The East Hampton-based author, and Press contributing columnist, had his most memorable brush with the Beatles in the fall of 1980. He was sitting in the living room of Waterfall—McCartney’s two-bedroom country cottage in Sussex, England—when the musician asked Mr. Gaines if he wanted to smoke a joint with him.

They hopped into McCartney’s brand new Mini Cooper and set out for a drive. The ex-Beatle and his wife, Linda, didn’t smoke marijuana in the house because of their children, he explained in between drags.

“I suddenly had this overwhelming epiphany that I was with Paul McCartney sharing a joint,” Mr. Gaines wrote in a recently published column. “So I told him, ‘It’s really unbelievable to me that I’m being driven around the English countryside by Paul McCartney.’ McCartney thought for a second and said, ‘Some days, it’s really unbelievable to me that I’m Paul McCartney.’”

All these years later, Mr. Gaines will often see the musician out and about, as do many East End locals and tourists alike.

Former East Hampton resident Wes Connors, who now lives in California, first met McCartney in a record shop on Main Street in the early 1970s, he recalled last week in an email. It took a number of years before the young boy realized that the former Beatle summered just down the street from his own home.

Encounters with McCartney became expected for Mr. Connors, though increasingly nerve-wracking as he got older and grasped his neighbor's fame.

Not everyone gets the luxury of preparation. Caroline Doctorow, who now lives in Bridgehampton, certainly didn’t.

It was 1989 and she was just starting out her career as a musician on the East End. She walked into C-Hear Studios—which, at the time, was located on Main Street in Bridgehampton—only to find McCartney finishing up his own session. He had written and recorded a song for his father-in-law, Lee Eastman, called “Happy Un-Birthday,” which poked fun at McCartney’s belated gift.

“Paul spotted me walking in with my guitar and said in his beautiful accent, ‘Got a session, eh?’” Ms. Doctorow said last week during a telephone interview. “As stunned as I was to see him standing there right before me, I think I managed a reply.”

After he left, the engineer gave Ms. Doctorow a bootleg copy of McCartney’s song, which she still owns.

“We were fellow musicians,” she said. “That’s how he made me feel, anyway, which was very nice of him.”

He carried that sentiment to The Stephen Talkhouse in Amagansett three years later, according to manager Peter Honerkamp. After G.E. Smith and the High Plains Drifters played their set, he hopped on stage for a rendition of “Blue Suede Shoes.”

“I was playing that night,” guitarist Jim Turner said last week during a telephone interview. “He said, ‘In the key of G,’ and the band cranked it off. It was almost like I was numb. After the show, he came upstairs to the green room. I was standing in the middle of the floor, thunderstruck, just talking to him.”

McCartney has returned to the Talkhouse twice since then, Mr. Honerkamp said—once in 2011 to see Gary Clark and just this past August for a concert by Jimmy Buffett and Tom Curren.

“In 2011, I chased him down the street so my son could meet him,” Mr. Honerkamp wrote in an email last week. “He was, again, unassuming and gracious with his time. A true gentleman.”

The former Beatle was, easily, the last person Shaye Weaver, an East Hampton Press reporter and Springs resident, expected to encounter when she went out to dinner with her family two summers ago at Nick & Toni’s in East Hampton.

First, Alec Baldwin walked in the door. Next came Woody Harrelson. So when her aunt said, “Oh my God, here comes Paul,” Ms. Weaver thought she was joking.

She wasn’t.

“I turned around and there he was,” Ms. Weaver—a self-confessed Beatles fanatic—said last week during a telephone interview. “I was like a deer in headlights. Everyone in my family was like, ‘Shaye! It’s Paul!’ I just sat there, stunned.”

It didn’t take long for the now 26-year-old to realize this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, she said. And she was blowing it. She got up from the table and headed toward the back where McCartney was sitting with his family and Mr. Harrelson.

As soon as she approached, they met eyes.

“But then I freaked out and smiled and turned around on my heel and ran into the bathroom. And jumped up and down five times,” she laughed. “I couldn’t handle it.”

Growing up in Georgia, Ms. Weaver first heard the Beatles as a little girl thanks to her father, Jack, but didn’t latch onto the band herself until she was faced with heartbreak.

She was just 13 when her father died, and the young girl grasped onto every memory she had of him, including his music. Years later, in 2009, she dove even deeper into the Fab Four while playing the music video game, “The Beatles: Rock Band,” which helped her learn the intricacies of her favorite songs.

With nearly 10 Beatles tribute band concerts under her belt, Ms. Weaver finally caught a transatlantic flight to Liverpool, England, last year to see where it all began. She took the Magical Mystery Tour and visited key locations, such as Penny Lane and Abbey Road—where she walked across the street and re-created the famous album cover of the same name.

“That was a highlight,” she said. “I think the Beatles were so transformative and so iconic that I don’t think there’s any way that’s going to be lost through the ages. I’d teach my kids about the Beatles, absolutely.”

Mr. Lauro didn’t have to. His 19-year-old son came to discover the Fab Four on his own, he said.

“I can say that I have very little in common with him, music-wise, but you want to know something?” he said. “He has every Beatle CD on his iPod. I didn’t have to convince him. What does that say? That says it crosses generations. It’s something real. It’s something that has lasted. God knows how long, but it has lasted.”

Bay Street Theatre in Sag Harbor will kick off its three-day Beatles celebration, “It Was 50 Years Ago Today,” on Friday, February 7, at 8 p.m. with a screening of Joe Lauro’s film “Legends: The Beatles.” Tickets are $15. The Beatles music mania will continue on Saturday, February 8, at 8 p.m. with “Celebrating the Beatles,” an evening of Beatles songs performed by a number of East End performers, including Inda Eaton, Gene Casey, Corky Laing, Mama Lee & Rose, Joe Delia, Dawnette Darden, Joe Lauro, Caroline Doctorow, Jim Turner and Jewlee. Tickets are $25 in advance or $35 at the door. The weekend will culminate on Sunday, February 9, at 7 p.m. with a screening of the Beatles American debut on “The Ed Sullivan Show,” as well as rare footage from their first visit to Manhattan just hours before the 1964 broadcast. Tickets are $5. A Fab 4 Fan Pass, which includes admission to all three nights, is $40. For more information, call 725-9500 or visit baystreet.org.