The federal Fair Housing Act was spawned from the civil rights movement in the late 1960s to protect potential homebuyers from discrimination based on their protected class: race, color, national origin, religion, sex, familial status or disability.

The legislation also outlaws a property owner, property manager, developer, broker, mortgage lender, homeowners association or insurance provider’s refusal to sell. They are likewise prohibited from promoting available housing through exclusionary advertising, or any action that might coerce, threaten, intimidate or interfere with a person’s right to open housing based on a protected class.

It’s not an empty threat: Lawsuits are regularly filed, and they sometimes involve advertisements that use language that can be construed by the court as exclusionary, according to Long Island Housing Services. Ian Wilder, the nonprofit’s executive director, said even seemingly innocuous phrasing can get people into trouble.

“If you are putting limits on people, then there is a good chance you are violating a fair housing law,” Mr. Wilder said. “People get into trouble for discriminatory advertising all the time. Any time you are putting something into writing or saying something to someone who knocks on your door, what you say can be a problem. My advice is to stick to simpler descriptions—about how many bedrooms, square footage and amenities.”

The housing nonprofit is a resource for anyone who feels they have been discriminated against and for homeowners and organizations to keep their selling and rental practices up to snuff.

“Our job is not to find people who are doing something wrong—our job is to help people do what’s right,” Mr. Wilder said.

Suffolk Federal Credit Union, a Medford-based mortgage lender with East End locations in Southampton and Eastport, is one of the latest financial institutions to reach a settlement of complaints—cash subsidies for borrowers in certain Suffolk County zip codes west of Southampton, and a promise to provide additional staff training to prevent potential discrimination, according to a joint statement released by the Long Island Housing Services and the credit union in July.

The fair housing advocacy group sued over possible discrimination against black and Latino homebuyers who sought information about mortgage loans. The credit union said in the statement that it denies any discriminatory lending and paid the settlement to avoid a lengthy litigation process.

Real estate agents and sellers want to avoid that headache as well, said Andrew Lieb of the strategic legal partner firm Lieb at Law P.C. Mr. Lieb teaches real estate property law to brokers and would-be brokers through the Lieb School.

Brokerages tap his expertise to train brokers to follow the law, but also to be on alert for people who seek to exploit the housing rights legislation—because it happens often, and almost always ends up in a settlement, forcing firms to shell out big bucks.

And the South Fork market is a prime location to target because of the high value of real estate—which also makes it an uncomfortable topic for brokerages to discuss.

“An average broker believes that clients want to discriminate, but the best broker knows that their clients are just scared and need to be educated on the do’s and don’ts,” Mr. Lieb said during an interview at his firm in Center Moriches.

He noted several nefarious examples that brokers watch out for, including people—armed with recorders—backing sellers into a corner by asking questions like:

“What—you won’t sell to me because I’m gay?”

“You think us Muslim people shouldn’t live around you white people?”

“Do you think I can’t afford this place because I am Chinese?”

Oftentimes, sellers are caught off guard and don’t know how to respond, Mr. Lieb said. They are already stressed from putting their home on the market, and one slip of the tongue could land them, or a broker, in court.

Most of the time, sellers discriminate through “ignorance,” he said, and the broker’s job is to protect them from making an unforced error, whether with a scammer or a real potential buyer, by offering “empowering choices that substantiate emotional responses with non-discriminatory rationale.”

“You got to have a paper trail that memorializes and makes a record of non-discriminatory preferences for the transaction,” Mr. Lieb said. “If the seller doesn’t want to deal with a buyer who has a mortgage contingency, it needs to be written down from the beginning so any potential lawsuit down the road is useless.”

But the preference can never be attached to the demographics of the buyer, he emphasized. Here’s a more nuanced situation:

A retired couple wants to downsize after living and raising a family in their three-bedroom residence for the past 20 years. For many years, the children would go to school around the corner during the week; father and daughter would enjoy long days on the beach, while mother and son were always at the baseball field. On Sundays, they’d go to church.

The broker comes back with three potential buyers making solid offers. But the couple feels another family should enjoy the home as much as they did—they want to know who and what the buyers are like before they seal the deal.

Does this have the potential to lead to a housing discrimination case? Maybe—the answer is somewhere in the gray area, Mr. Lieb said.

“The law doesn’t work with ‘yes’ or ‘no,’” he said. “But the broker’s job is more about risk assessment and limiting their client’s exposure to what can get them sued.”

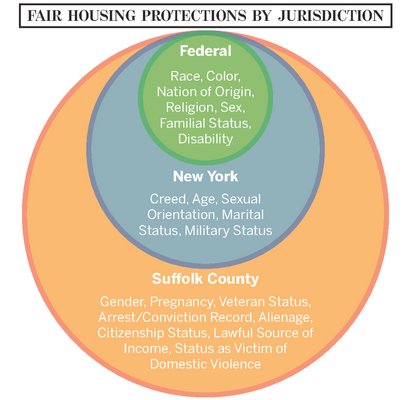

Signs point to “yes” when there is blatant discrimination of a homebuyer’s protected class. What is a protected class gets complicated, as state, county and town codes add criteria. For instance, age is included in New York, and source of income is included in Suffolk County.

Mr. Lieb said it’s best not to try to remember what is considered a protected class but rather to always be inclusive and never talk about demographics.

“Sellers and brokers should look at buyers like they are dancing dollar bills,” he said. “This isn’t a marriage—it’s a transaction.”

Brokers should stick to what Mr. Lieb calls “defensive brokering.” Always talk about the condition of the property, always be inclusive, always have a paper trail of non-discriminatory preferences, and always record interactions with buyers—but never discuss anyone’s demographics.

There are exceptions to fair housing law—the most notable is the Mrs. Murphy exemption, according to Mr. Wilder. It’s targeted at landlords who share housing with a tenant, such as an empty nester or elderly widow renting out rooms. Also exempt, when it comes to age and familial status, are 55-and-over communities.