Even if it’s not a widely discussed topic, it’s no secret that organized crime has historically had a heavy hand in the world of heavyweight boxing. In the last century, fixing fights brought in a lot of money for a lot of underworld players, and the details behind these bouts have often been veiled in ways that make them feel more like fiction than fact. But now, thanks to a new book by East Hampton author Jeffrey Sussman, you can read the whole true story for yourself.

Mr. Sussman’s book, “Boxing and The Mob: The Notorious History of the Sweet Science,” was released earlier this month by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, and in its pages the author takes an intentional dive into the history of mob involvement in professional boxing. Along the way, he also introduces readers to the legendary characters involved in the sport—both in and out of the ring—throughout the 20th century.

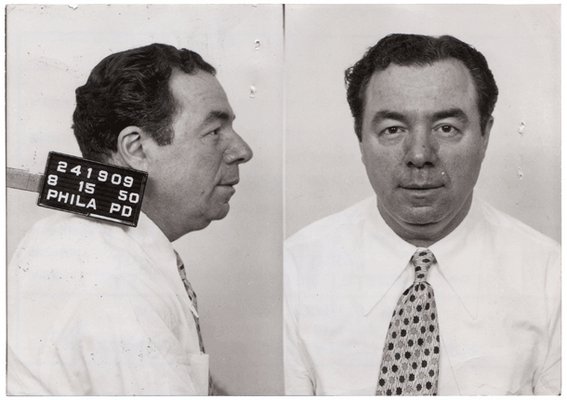

The cast of characters profiled in “Boxing and The Mob” reads like a call sheet for a Martin Scorsese film: names like Owney Madden, a bootlegger and killer who controlled heavyweight boxing in the 1930s; Frankie Carbo, a member of Murder Inc. who dominated the sport in the 1950s and 1960s, and was responsible for the killing of fellow mobster Bugsy Siegel; and Frank Blinky" Palermo, a fight manager who fixed virtually every fight in which he had a controlling interest.

On Saturday, June 8, Mr. Sussman will be at East Hampton Library at 2:30 p.m. to talk about “Boxing and The Mob.” It’s an appropriate venue, given that much of the research for his book was done at that very library, and in a recent interview there, Mr. Sussman explained that many of the details in the book came from FBI files that are now available online. He also tracked down newspaper articles and a number of out-of-print books with help from Steven Spataro, head of East Hampton Library’s reference department.

“Then I also interviewed people who had a lot of information to impart to me,” added Mr. Sussman. “I uncovered things I had an inkling about and developed more information. Because of my interest in boxing, there were not many surprises. But I was surprised by how much information I found. I don’t think the public generally knows about it.”

One of the facts the public may not know is that when boxer Sonny Liston, who once fought Muhammad Ali, died of an apparent overdose at his Las Vegas home in 1970, it was, in all likelihood, a mob hit.

“They killed him,” Mr. Sussman said matter-of-factly. “He died of an overdose—but he was scared of needles. They went to his home in a friendly way, doped his drinks and gave him a lethal dose of heroin.”

The reason?

“One theory is, they owed Liston a lot of money and hadn’t paid him for the fixed fights, and he said he would go to the government to squeal on them,” Mr. Sussman explained. “He was also dealing drugs in Las Vegas, and there was a feeling that he was impinging on the mob’s territory.”

Money has always been the major motivator behind any mob operation. Based on how rich organized crime members got from bootlegging during Prohibition in the 1920s, it should come as no surprise that when alcohol became legal again in 1933, gangsters quickly sought out another line of work.

“It was so opportunistic—whenever they see a way to make easy money, the mob will do it,” said Mr. Sussman. “So much money was made from Prohibition, boxing seemed like small potatoes.”

But those potatoes were crucial in the Depression-era 1930s, and in order to understand why boxing became the sport of choice for the mob, you need only consider the Black Sox scandal of 1919.

That was the year the Chicago White Sox faced the Cincinnati Reds in the World Series. Eight players on the White Sox team, under the influence of New York mob boss Arnold Rothstein, intentionally threw the series. Only pitcher Red Faber was not in on the fix: He had missed the entire series due to illness and injury.

The resulting fallout and lawsuits from the Black Sox Scandal made the mob realize that they needed to find a much easier sport to fix. That sport was boxing, because, as Mr. Sussman sagely noted, “You only needed to bribe two, instead of nine … And you only really needed one who was in on it.”

Once they realized how easy it was to fix a fight, the mob started raking in millions. It didn’t hurt that, more often than not, the boxers they were intimidating into taking dives in the ring were extremely poor and vulnerable. Desperate for money, they were often from families that had only recently arrived in the United States.

“Boxing was always a way out for the poor,” Mr. Sussman said. “The first successful boxers were Irish, some German, then Jewish, also Italian. When the Jewish boxers left, the Italians became dominant. Then came the black boxers, then Hispanic boxers came in. With a few rare exceptions, they were from a poor background, with parents earning very little money.

“If they were smart, they got out before they got brain damage.”

One of the most powerful mob boxing promoters to ever fix a fight was Frankie Carbo of the Lucchese crime family. “He was a terrible gangster and had killed 19 members of Murder Incorporated,” said Mr. Sussman.

Working with other mobsters, including Blinky Palermo, Carbo became known as the “Czar of Boxing” by fixing a huge number of high-profile boxing matches beginning in the 1940s—and it wasn’t about the heavyweights.

“It was the welterweight and middleweight division they controlled. Every fight from late ’40s to early ’60s was controlled by them,” Mr. Sussman explained. “And they fixed all the fights.”

Jake LaMotta (aka the “Raging Bull,” depicted in the Martin Scorsese film of the same name) was one of those fighters, and he felt he should be the middleweight champion, because he wouldn’t deal with mob and refused to take a fall—until he did. In November 1947, LaMotta caved to the mob’s bidding by intentionally throwing a fight against Billy Fox, in return for a shot at the middleweight title, which he later won.

“He just stood there and the [Madison Square Garden] crowd realized it was fixed,” said Mr. Sussman of that fight. “Jake LaMotta bet on Fox to win. He didn’t get a shot at the title immediately, but he became the middleweight champ by beating Marcel Cerdan, who was Édith Piaf’s fiancé. In a rematch, Cerdan was supposed to come to the United States to train but died in a plane crash.”

Eventually, Carbo’s luck ran out too when his threats of boxers and managers went too far. The FBI investigated and, under Robert F. Kennedy’s Justice Department, prosecutions sent Carbo to prison for 24 years, Palermo for 15.

“Carbo was still controlling boxing from prison,” Mr. Sussman said.

When asked if boxing still operates the way it did in those days, Mr. Sussman said that in 1993, Sammy “The Bull” Gravano testified about corruption in boxing.

“He said it doesn’t operate the same way now as it then did. ‘Then, we would own a manager and, through him, own a boxer, and the boxer didn’t know,’” said Mr. Sussman, recalling the testimony. “You don’t have to fix it now, because the purses have gotten so big. Rocky Graziano had some fights late in his career. He needed the money and got $50,000 whether he wins or loses.

“Even if you want to fix a fight today, it’s still the easiest game to fix in the world,” Mr. Sussman added. “At the lower level, it still goes on. You just buy one or two judges, and a fight is based on points, and they will know who’s going to win. The referee will separate fighters to prevent a knockout, and the judge awards the points.”

Mr. Sussman’s interest in boxing isn’t limited to writing about the sport. As a teenager, he also participated in it. “When I was 12, I was a skinny little kid, and my father was worried I’d be picked on. So he got me a jump rope, gloves and set up a gym in the basement,” he said.

His father, who was a boxer himself, eventually took him to Stillman’s Gym on 8th Avenue off 54th Street. The gym was upstairs, recalled Mr. Sussman, and his father paid a middleweight $100 to give him 10 lessons. The place was filthy, he said, because the boxers wouldn’t have stood for it if it was clean.

“It was exciting, and it did give me a lot of self-confidence, maybe initially too much” said Mr. Sussman. “I thought I was a tough guy, but the guy who gave me lessons disabused me of that notion. He said you could still get your head beaten in.

“But there were gamblers, trainers, gangsters and promoters,” Mr. Sussman added. “It was a complete menagerie of colorful guys and dolls.”

Jeffrey Sussman discusses “Boxing & The Mob: The Notorious History of the Sweet Science” on Saturday, June 8, at 1 p.m. at East Hampton Library, 159 Main Street, East Hampton. Call 631-324-0222 to reserve. Mr. Sussman will also take part in a Westhampton Free Library talk at noon on Saturday, June 15, at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, 40 Main Street, Westhampton Beach. Other appearances include Shelter Island Library on July 5, the Hampton Library in Bridgehampton on September 14, and Southampton’s Rogers Memorial Library on September 25.

"