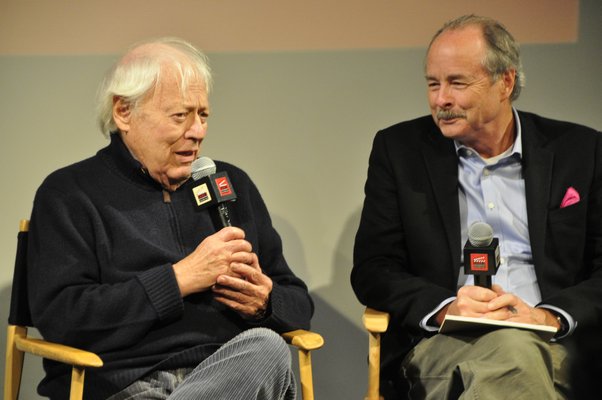

The credits rolled. The projector powered down. Andrew Botsford and Jason Epstein took their seats in front of a packed house at Bay Street Theater in Sag Harbor following the screening of “The 50 Year Argument” during the Hamptons Take 2 Documentary Film festival, Martin Scorsese’s latest doc examining The New York Review of Books.

“So, an impressive birthday party for the child you gave birth to,” Mr. Botsford said to Mr. Epstein, one of the magazine’s founders.

“I …” Mr. Epstein started, before the audience interrupted with a round of applause.

The year was 1963. Mr. Epstein and his wife, Barbara, were hosting a dinner at their apartment on West 67th Street during the New York newspaper strike. Seated at the table were their neighbors, Robert Lowell and his wife, Elizabeth Hardwick, who had recently called The New York Times Book Review a “provincial literary journal” in Harper’s, where renowned editor Robert Silvers worked.

Mr. Epstein, an editor at Random House, said he felt an opportunity on the horizon. It was their time to compete. And it was a success from the beginning.

“When we decided that evening with the Lowells that we would start this paper during the newspaper strike, I said, ‘An indispensable factor has to be Bob Silvers,’” Mr. Epstein recalled. “He has to be willing to come and join us. I thought maybe he wouldn’t, because he had a very good job at Harper’s magazine. But when I called him the following morning and asked if he would be interested in such a thing, he said, ‘Yes, on one condition: that Barbara and I edit it together.’

“And that became a partnership,” he continued. “Not always an easy partnership, by the way, but a very productive one. Unfortunately, there wasn’t much film about Barbara for the purpose of this documentary, but she and Bob were in every way equals.”

They took the helm with confidence and brilliance, Mr. Epstein said, as the magazine evolved from a review of books into an “intellectual, philosophical conscience for the intellectual world,” Mr. Botsford said.

“That would be inevitable,” Mr. Epstein said. “All we know, all we are, are books. Books are us. That’s who we are. And without them, and without taking them seriously, we would be lost. Books are everything. And that was since the beginning we thought that. We took them very seriously.”

At one point, Ms. Epstein, who died in 2006, decided on a 140,000 circulation for the magazine, according to her widower, who has lived in Sag Harbor since the 1970s. “So, it’s still 140,000. It just stays right there,” he laughed. “And whenever somebody dies, somebody steps in his place. The renewal rate, which is the crucial number in the magazine business, is about 95, 96 percent. Which means most people aren’t dying.”

“Obviously, because they read The New York Review of Books,” Mr. Botsford said. “So that’s the answer for all of us.”

If the readership is immortal, so is Mr. Silvers, according to Mr. Epstein—“He’ll always be there,” he said, shrugging off the “What will happen after Bob?” question. The lively discussion and debate will live on, as will the never-ending task of understanding the world and “who we are,” Mr. Epstein said.

“Sometimes, that’s an awful thing to find out, by the way—who we are—but that’s what The New York Book Review is about … I think it’s going to go on forever.”

The audience applauded.

“Let’s hope that it does,” Mr. Botsford said. “Let’s certainly hope that it does.”