When we think of Brooklyn writers, we don’t necessarily think of Truman Capote. We picture him in his apartment at the United Nations Plaza or at his cottage in Sagaponack, at Studio 54 in Manhattan or at Bobby Van’s in Bridgehampton.But he did actually live in Brooklyn while he was working his 1958 novella “Breakfast at Tiffany’s.”

“I live in Brooklyn. By choice,” he begins his essay, “A House in the Heights”—the centerpiece of a new book, “Brooklyn: A Personal Memoir by Truman Capote With the Lost Photographs of David Attie” (The Little Bookroom, $29.95,105 pp.).

Capote lived in two basement rooms in Brooklyn Heights that he decorated with, among other things, ceramic cats, paperweights and the skeletons of snakes.

The house, which had probably once belonged to a ship’s captain, had a tall central spiral staircase and 28 rooms. When the landlord was out, Capote often took friends on a tour of the house explaining, as George Plimpton writes in his introduction, that it was “his house, all his, and that he had restored and decorated every room.” It wasn’t and he hadn’t.

The book itself has a unique publishing history. John Knowles, author of “A Separate Peace,” commissioned Capote’s original essay about Brooklyn while working as an editor at Holiday magazine. It was to be illustrated with photographs by David Attie, an up-and-coming young photographer who created the photo montages that graced the original cover of “Breakfast at Tiffany’s.”

Holiday used only four of the many photographs Attie took of the house and neighborhood, and none of the portraits of Capote.

The essay went out of print and was republished in 2001, without the pictures. But in 2014, Attie’s son, Eli, made an astonishing discovery. Inside a dust-covered wooden box were the photographs of Capote, stuffed in a small manila envelope, more than 50 years after they were taken.

In addition to the Capote portraits now included in the most recent publication, there are wonderful pictures of life in Brooklyn: children playing in the streets, boys swimming in the East River, a father walking with his little daughter, the elderly taking their ease on a park bench, or in a hotel lobby. There are merchants standing at their storefronts, waiters about to attend to their customers, revelers enjoying a wedding reception, brownstones with their great arabesques of ironwork. The photographs are wonderfully poignant, plunging the current reader into a deep well of nostalgia.

Attie was a great noticer. Capote was as well; nothing escaped his eye. It is what made his writing so compelling. “Window boxes bloom with geraniums; according to the season, green foliated light falls through the trees or gathered autumn leaves burn at the corner; flower-loaded wagons wheel by while the flower seller sings his wares; in the dawn one occasionally hears a cock crow, for there is a lady with a garden who keeps hens and a rooster. On winter nights, when the wind brings the farewell callings of boats outward bound and carries across rooftops the chimney smoke of evening fires, there is a sense, evanescent but authentic as the firelight’s flicker, of time come circle, of ago’s sweeter glimmerings recaptured.” One had almost forgotten what a graceful and evocative writer Capote was. The essay is a small gem.

The story of the discovery of the photos, told in an afterword by Eli Attie, is fascinating. In trying to preserve his father’s pictures and get them shown in galleries, he was actually searching for photos of celebrities, and accidentally found some portraits of Capote, along with the negatives for the photos that were to accompany Capote’s article.

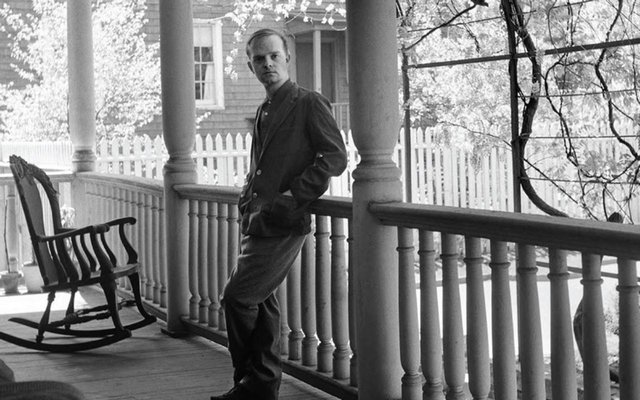

“When I saw the negatives printed, my jaw hit the floor,” he writes. “These were the coolest pictures of Capote I’d ever seen, framed like shots from a Hitchcock movie. The still young, steely-eyed scribe looks like he’s creating his own mythology right in front of the camera.

“How had I never seen these before?” he continues. “Why were they not hanging in major museums, let alone languishing unseen in a dust-covered wooden box?”

He’s absolutely right about the portraits, which he almost lost, having left them in a New York taxi and recovered them through the efforts of a high school friend, who was the deputy commissioner of transportation. One wonders how many other such works have been lost in similar ways.

Without them, we are probably the poorer. With these, we are certainly richer. This is quite simply a lovely book.