Three weeks into rehearsals at East Hampton’s John Drew Theater for his play, “Equus,” Peter Shaffer, the English dramatist whose credits also include “Amadeus,” “The Royal Hunt of the Sun,” “Black Comedy,” and scores of others, and whose awards and accolades would fill a book, settles in for an interview at Guild Hall.

Hailed on both sides of the Atlantic for his masterly command of the theater and the boldness he has brought to it, the 84-year-old playwright has become a familiar figure at the John Drew over these past weeks, attending rehearsals, taking notes and tweaking his script.

“Equus,” which premiered in London in 1973 and went on to repeat its enormous success in New York, winning the 1975 Tony Award for Best Play and the New York Drama Critics Circle Award, has had many, many highly praised productions and would seem to require no tweaking. Yet, while Mr. Shaffer stressed that he has no intention of dramatically altering his play, he noted that recent revivals in London and New York had prompted him to make small changes.

“You learn things here and there,” he said, such things as “where a different approach in the phrasing would be an improvement.”

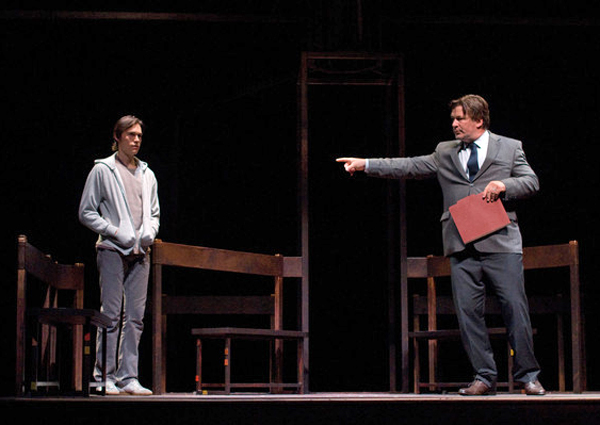

Already in previews this week, it will be a slightly altered “Equus” that opens on Friday, June 11, and remains at the John Drew until July 3, directed by Tony Walton and starring Alec Baldwin and the young British actor Sam Underwood. But the story it tells and the disturbing questions it raises will remain unchanged: Alan Strang ( Mr. Underwood), a stable boy who has committed a seemingly motiveless outrage—he has blinded six horses by plunging a spike into their eyes—is brought to psychiatrist Martin Dysart (Mr. Baldwin), who must investigate the facts and the circumstances and enter the mind of his patient to discover what could have driven him to commit such a crime.

It was an actual news story about a British youth who blinded 26 horses that inspired him to write “Equus,” Mr. Shaffer confirmed, adding that though he had not been inclined to investigate the details of the incident at the time, nor had he managed to dismiss it from his mind.

“I found it to be rather haunting, to some extent frightening,” said Mr. Shaffer, speaking slowly and thoughtfully, giving the matter his full attention, though he has no doubt been asked about the play’s inspiration hundreds of times.

“It wouldn’t leave me alone, it wouldn’t go away,” he said of the mysterious, deeply troubling incident.

It was because “it demanded to be explained, to be dealt with in one’s head,” that Mr. Shaffer took on the task of creating a fictional mental world in which such a deed could be comprehensible.

In this world, as Dysart’s examination of the state of mind of the damaged teenager reveals, a fantasy love for horses has reached the extreme of deification. And while there is much misery in the boy’s life and he has committed a horrible crime, his ritualistic worship of horses has given him moments of awesome passion and ecstasy—powerful states that contrast uncomfortably with the psychiatrist’s own dispassion and disillusion.

As the “treatment” progresses, it becomes increasingly clear to Dysart that “curing” the boy and making him socially acceptable will exact a price. (“Passion can be destroyed by a doctor, it cannot be created.”) In the end, the psychiatrist’s state of mind proves almost as unsettled as that of his patient as he grasps the contradiction between the rational, civilizing mission of his chosen profession and the undeniable yearning his relationship with Strang has awakened in him for a more passionate existence.

For Alec Baldwin, the opportunity to portray this complex character and his contradictions on stage is apparently one he has long sought.

“He had expressed a desire to do it some time ago,” said Mr. Shaffer. The stars had not aligned properly for the project until this year, when Mr. Baldwin suggested the play for John Drew’s summer schedule and things fell into place. Mr. Walton was available to direct and Mr. Underwood declared himself “blown away” by the chance to come to East Hampton and work with theatrical legends.

“I was very pleased and delighted,” Mr. Shaffer said of Mr. Baldwin’s campaign for the play and enthusiasm for the part. “He is obviously an extremely good actor and so is Sam.”

Stephen Hamilton, known to many for his work as one of the founders of Bay Street Theatre in Sag Harbor, and for productions at the Stephen Talkhouse in Amagansett and at Guild Hall, has been cast as Alan Strang’s father, an atheist with little patience for fantasy of any kind who is married to a woman of merciless religion. Completing the cast are Kathleen McNenny, Jennifer Van Dyck, Shashi Balooja, Nehassaio de Gannes and Terrence Michael.

Mr. Hamilton has expressed delight at finding Mr. Shaffer so actively involved in the production. A new scene, delivered to him from the playwright two days before rehearsals began, did much to clarify his character’s motivation, he said, adding that “what Shaffer is doing by picking up the pen at this stage in his, and the play’s life, is not just a remarkable act of dedication to theater, it is a profound act of courage.”

For his part, Mr. Shaffer obviously regards his continued involvement as one of the joys of live theater. While two of his plays—“Amadeus” and “Equus”—have been made into movies, his preference is clearly for the theater.

“I think I would always much prefer to be making a piece for theater rather than making a film,” he said. “As a writer I don’t think you are nearly as much involved in making a film as you are in a play. A play is yours, very personal in a strong way, while a film is likely to be altered.”

The discovery that writing plays was “the thing I most wanted to do” came to him in early adulthood, but first fate had other plans for him. During World War II he found himself working at a job that had absolutely nothing to do with the theater.

“When I was 18, I was conscripted,” he said, “but not as a soldier. I was called up because the government in England had called up all the young miners to be soldiers.”

That turned out to be a terrible mistake when coal stockpiles dwindled alarmingly in their absence, threatening England’s ability to keep its war machine going.

“They couldn’t be extracted from the military,” Mr. Shaffer said of the real miners and so he, his twin brother Anthony, who is also a playwright, and many others were conscripted as substitutes.

“I was a coal miner for two and a half years,” he said, a “miserable” time that had just one bright side.

“I would occasionally escape for a weekend,” he explained. “In those days the theater was at its zenith and in each of the many different theaters were to be found John Gielgud, Laurence Olivier, Ralph Richardson, Sybil Thornton, Paul Scofield, Alec Guinness—I thought that theater was always like that.”

It was heady stuff and he seized the opportunity to see “every kind of great play.” When the war ended he went from the hell of the mines to the heaven of Trinity College, Cambridge—“a marvelous place”—and in 1954 his first play, “The Salt Land,” was presented on BBC television.

Having been born into what he called “the era of the well-made play,” Mr. Shaffer said that he knew early on that he wanted to escape from its bonds. That impulse has led him way beyond the four walls of the drawing room to a theater characterized by the boldness of his concepts and the creativity of his visions for staging them. He has made groundbreaking use of expressionistic theatrical techniques such as masks, mime and dance.

The breakthrough came in 1964 with his play about the demise of the Peruvian Incas, “The Royal Hunt of the Sun,” an unprecedented production that was characterized by one critic as “a musicless Verdi spectacular.”

“It was considered very bold for its day,” recalled Mr. Shaffer, and “having had this highly approved play of the Incas, which was like no theater that was actually running at the time or had been seen, I then was encouraged to spread my wings.”

With “Equus” he and John Dexter, whom Mr. Shaffer described as “a brilliant director who has been very, very influential in my life,” scored another victory for innovative, visually and intellectually enthralling theater.

“It’s by far the most thrilling live art we have,” declared Mr. Shaffer, whose daily presence at the theater is testimony to his enduring belief in its power.

“So three cheers for Alec Baldwin,” Mr. Shaffer said with a smile. He pushed for the play and has embraced his challenging role—“a very bold thing and a good thing he is doing,” pronounced the playwright, “and it’s lovely working with him.”

The box office at the John Drew Theatre at Guild Hall can be reached for tickets and information at 631-324-4050, or online at www.guildhall.org.