My love for local history began when I was archiving the collection at the Sag Harbor Historical Society’s Annie Cooper Boyd House on Main Street.

I spent a lot of afternoons alone there channeling Annie, the girl who rode bareback all the way to the bay and the woman who came back to this cottage as a young widow and remade herself as an artist. I started imagining the ancestral presence of Fannie Tunison, frequent visitor to the cottage and personages from Sag Harbor’s early past like Samuel L’Hommedieu who lived in the brick house down the street.

By March 2018, when the Suffolk County Historical Society mounted the Eastville Community’s exhibition of tintypes celebrating African Americans and Native Americans, I was compiling a bibliography of local primary resources on Native American history. I wanted to learn as much as I could about the first peoples who lived here. I kept thinking we are all living on stolen land, and I couldn’t reconcile myself to it.

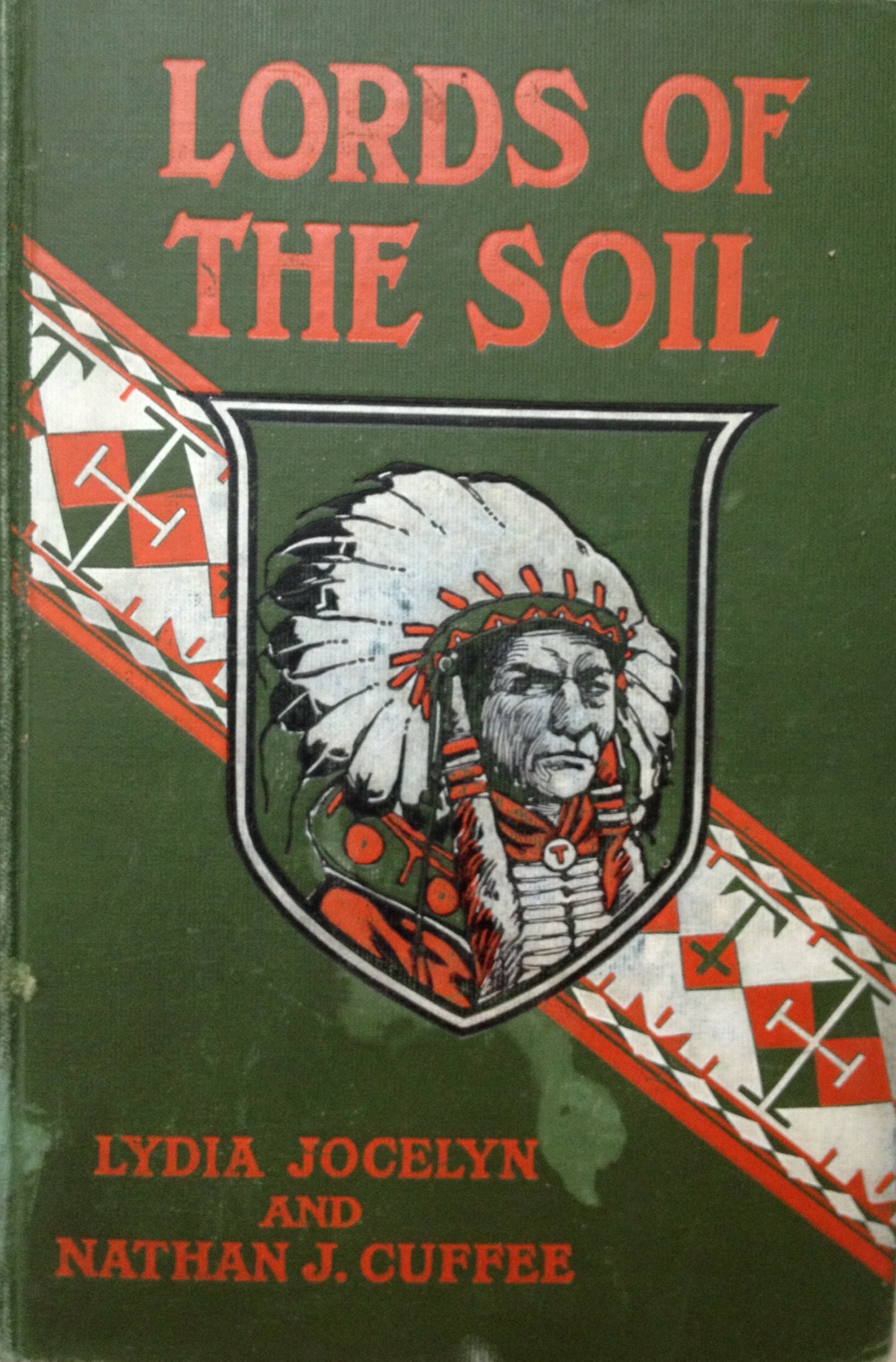

When I read the wall text next to the Reverend Nathan J. Cuffee’s tintype, identifying him as the first Native American writer published on Long Island, I knew I had to read the book. Almost everyone in Eastville was familiar with Cuffee’s novel, “Lords of the Soil,” but no one could tell me anything about his co-author, Lydia A. Jocelyn. So, I decided to take a trip to Boston in November 2019 and read through her papers at Harvard University. There, I found the original notes made at Cuffee’s home on Shelter Island, where these two people from different backgrounds came together to tell a barely fictionalized history of the Montauketts.

Happily, as archivist at Amagansett Library, my conversation with this book continues. I have found community as a guest in The Montaukett Women’s Circle Book Discussion Group. We are on chapter 41. This piece is about what I found out and why the book is a touchstone for those of us who live here now.

“Lords of the Soil: A Romance of Indian Life Among the Early English Settlers” by Lydia A. Jocelyn and Nathan J. Cuffee. Published by C.M. Clark. Boston, 1905.

Lydia Ann Jocelyn packed her stories with intrigue, murder, love and betrayal. Jocelyn was a scrupulous researcher, energetically lacing her historical romances with moral vigor and lush landscapes. In 1903, at the age of 67, having published seven books, countless short stories and a few dramas, Jocelyn left her commodious home in Connecticut to pay a visit to the Reverend Nathan Jeffrey Cuffee on Shelter Island. She was a writer in search of a story and Reverend Cuffee of the Eastville Band of Montauketts had a story that needed to be told.

Together, Cuffee and Jocelyn wrote “Lords of the Soil,” published in 1905 to much fanfare and critical praise.

As the novel opens on the sparsely colonized New England landscape, in and around the waters of Connecticut, Rhode Island and Eastern Long Island, we find ourselves beyond the time of first contact, referred to by Chippewa writer Louise Erdrich as “first collision” and well into what had become a game of land-grabbing on the part of the conquerors and accommodation on the part of the aboriginal population.

The book conjures a fatal romance between a dashing, two-faced English officer and the fictional statuesque, raven-haired beauty, Princess Heather Flower, daughter of Montaukett Sachem Wyandanch. It retells the kidnapping incident that, according to folklore, took place on her wedding night. A plumb line of the friendship between the angelic, blond, violet-eyed Damaris Gordon, affianced to the young English officer in question, and Heather Flower anchors the plot.

The first sentence places us in 1654, a period of warring interests by Dutch and English for control of land along the Northeast coast of America. By this time the local Algonquin population had already been decimated by European diseases and the carnage of the 1637 Pequot Wars. Aware of the vulnerability of his people, Wyandanch seeks an alliance with Lion Gardiner, commander of Fort Saybrook, in order to avoid paying tribute to his enemy Ninegret, leader of the Niantics.

Lion Gardiner’s acquisition of Man-cho-nock, or “Place of Many Dead,” which he named Isle of Wight (now known as Gardiners Island), is presented as a reward for his help. The facts are more complex. The “gift” was a transaction between two culture brokers who forged a lifelong bond by maintaining a lopsided quid pro quo; the Englishman having the advantage.

“... on Wyandance and his ‘friendship with the pale-faces.’

“True it is that he saw much of them, and to a degree was, in turn, flattered and coerced by them, now promised protection and rich reward to do this or that, or threatened with abandonment and disaster if he demurred. He saw and knew their growing power, and keenly felt the helplessness of his people to rebel, so isolated were they in their island home, so completely were they encircled by the coils of the serpent.

“Deeply conscious of this, and trembling for the fate of his race, what wonder that from time to time, we find him relinquishing, with unwilling hand, the heritage of the Lords of the Soil.”

Like its predecessors “The Life and Adventures of Joaquin Murieta The Celebrated California Bandit” by Yellow Bird (John Rollein Ridge) a Cherokee living in California published in 1854 and “Ramona” published in 1884 by Helen Hunt Jackson, “Lords of the Soil” is laced with stereotype and hyperbole. Its significance lies in bringing the seminal role of New England colonization into the Westernized mythology of America’s beginnings

While “Ramona” tells the story of the romance between a half-Native American girl and a Mexican of Spanish ancestry in Southern California and “The Life and Adventures of Joaquin Murieta” is a fast-paced, violent tale of a Mexican outlaw and his vengeful bandits during the days of the California gold rush, “Lords of the Soil” serves to reveal colonialism’s insidious aggregation of European influence on Native lifeways.

Writing at the beginning of the 20th century, Cuffee and Jocelyn use the vernacular of the 1600s refracted through a shared contemporary lens that includes a belief in the civilizing effect of Christian values. The plot twists are more straight forward than those of its two West Coast predecessors but the atrocities of the Northeast hold a mirror to the same ills — deracination, bigotry, racial violence and an inability to assimilate the immigrant (settler) experience into a whole cloth.

The co-authors backload the Indian tale with glimpses of the England left behind; conversational allusions to the rise of Oliver Cromwell, a tragic ocean encounter with a Dutch slaver, and the plantation life replicated on John Mason’s Connecticut Manor. Colonel Lawrence is cast as the love-smitten, landed retired military man on his way back to England who wants no part of the fiendish methods used by his fellow countrymen. Eccentric Quaker millionaire Deborah Moody whose mansion becomes the scene of a bloody attack by the Indians and a grisly murder is a study in contradictions.

Joceylyn’s copious notes, typewritten on both sides of onion skin paper, contain detailed descriptions of Indian traditions and penciled reminders to “ask Cuffee.” The pages of the novel brim with these jottings describing war canoes made out of carved birch that hold 10 warriors and a wedding feast where rude ovens of cobblestones made in the earth emit the savory odor of venison, bear and wild fowl, while an immense oval mound with a base of stones heated to whiteness send out occasional whiffs of steam from bushels of quahogs, oysters and mussels that were roasting as only Indian squaws could prepare.

No stranger to New England history, Jocelyn’s great-great-grandfather led troops during the French and Indian wars. He successfully ran the gauntlet as a captive, earning a native belt. Her great-grandfather was a major in the Revolutionary War fighting at Bunker Hill, and her husband served the Union in the Civil War.

Born in Vernon, Connecticut, in 1836, Lydia Ann Jocelyn married the Reverend Harry Weston Smith, a Connecticut preacher, when she was 22 years old. Reverend Smith preached throughout New England. In 1876 he traveled to Deadwood, South Dakota, where he became a missionary to the miners and Indians in the frontier town of Black Hills. While on his way to give a sermon, he was shot and killed by a member of the Sioux tribe waiting in ambush. After he died, she was able to support her children as a writer.

Nathan Jeffrey Cuffee was born in 1845 to Montaukett Jason James Cuffee, a whaler and laborer, and Louisa R. Cotton Cuffee, a Narragansett. He grew up on Liberty Street in Sag Harbor. He and his wife, Marie Louise Payne, who had immigrated from Barbados when she was 11, had three children. By the time Lydia Jocelyn Smith visited him in his Shelter Island home, he had grown blind, but this did not deter him from continuing to work as an eloquent activist on behalf of the Montauketts.

Cuffee appeared in court in 1900 at the age of 46 in a group effort among the Montaukett, Narragansett, Mohegan and Shinnecock to salvage the loss of the Shinnecock Hills in an illegitimate forging of documents that lead to the loss of the hills in an 1859 transaction. As this book was becoming popular in 1906, the New York State Legislature passed an Enabling Act. The bill gave the Montauketts a standing in court, as a tribe, (a position hereto denied them) and the right as a tribe to initiate legal action. (Previous attempts to sue for return of their land failed, when it was ruled that they had no standing in court). Both Jocelyn and Cuffee died in the winter of 1912, seven years after their collaborative effort was published: Jocelyn at the age of 75 and Cuffee at 58.

“Lords of the Soil,” captures a moment in 17th century Long Island history when the English system of deeds, patents and land grants imposed irreversible change on its first inhabitants and came to define the character of its towns. Today, we are left to address the geographical and psychological detritus of dispossession and displacement. Ours is a global reality — we share data, we share knowledge, we share disease, we share the consequences of unrepentant avarice.