LongHouse Reserve, the famed East Hampton outdoor sculpture garden, welcomes Ai Weiwei’s “Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads: Bronze,” an exhibition opening to the public on Wednesday July 8. The 12 monumental bronze animal heads — each approximately 10-feet tall and representing the traditional figures of the Chinese zodiac — will be installed around the perimeter of LongHouse’s outdoor Albee Amphitheater and will remain on view through October 2021.

This sculpture series by the world-renowned Chinese artist will mark the 50th installation of the series around the world and the third time the artist has participated with LongHouse. In 2013, he was honored with the LongHouse Award. At the time under house arrest in Beijing, he sent a video as an acceptance speech. In 2013 Ai’s “Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads: Gold” was also exhibited at LongHouse Reserve.

LongHouse Reserve is one of over 45 international locations that have hosted the “Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads: Bronze and Gold” series during the last decade. The enormous distances the Zodiac Heads have travelled can be compared with the experience of many, including the artist.

In April 2011, Ai Weiwei was detained for 81 days and later released from secret captivity by Chinese Authorities, but his passport was confiscated and he remained under house arrest until July 2015. For the duration of the “Zodiac Heads: Bronze” exhibition in Chicago in 2014, the sculptures were hooded as a reminder that the artist was still held in China. In 2016 Ai was granted his freedom and he visited the National Gallery in Prague to see the “Zodiac Heads: Bronze” installed at a museum for the first time in person.

Each of the “Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads: Bronze” sculptures ranges in weight from 1,500 to 2,100 pounds and is supported by a buried marble base weighing 600 to 1,000 pounds. They are displayed in cosmological order according to the traditional Chinese zodiac: Rat, Ox, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Goat, Monkey, Rooster, Dog and Pig. The sculptures’ combined weight of over 46,000 pounds will require massive lifts to move them into place among the trees and flowers of LongHouse’s gardens.

The sculptures are re-envisioned versions of the original 18th-century heads that were designed during the Qing dynasty for the fountain clock of the Yuanming Yuan (Garden of Perfect Brightness), an imperial retreat outside Beijing. The ornate European-style gardens were originally designed by two European Jesuit priests. In 1860, during the Second Opium War, British and French troops looted the heads during the destruction of Yuanming Yuan. Today, seven heads — the rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, horse, monkey, and boar — have been found; the location of the other five — dragon, snake, goat, rooster, and dog — are unknown. The ownership of the original works remains the subject of international controversy, with various Chinese collectors making a bid to reunite these significant historical sculptures whenever they come to auction.

By reinterpreting these objects in a contemporary context, Ai Weiwei stimulates dialogue about the fate of artworks that exist within the dynamic (and sometimes volatile) cultural and political settings of China and beyond. Ai is widely known for his engagement with Chinese history as a shifting site open to reevaluation rather than a static body of knowledge. His adaptations of objects from the ancient Chinese material canon — such as furniture and ceramic objects — are appreciated for their subversive wit, twisting traditional meanings toward new purposes often by destroying the artifact and its original, pure form. Ai Weiwei thinks of these heads in the context of looting and repatriation, as well as symbols of Chinese nationalism, allowing visitors to question the ways in which a historical narrative can be made to serve different purposes.

“My work is always dealing with real or fake authenticity, and what’s the value, and how the value relates to current political and social understandings and misunderstandings,” states Ai Weiwei: “I think [there’s] a strong humorous aspect there. So I wanted to make a complete set [of zodiac heads], including the seven original and the missing five.

Through his recreation of these cultural objects, Ai throws into question the importance of these artworks as it concerns Chinese history. “I don’t think that it’s a national treasure,” he added. “It has nothing to do with national treasure. It was designed by an Italian and made by a Frenchman for a Qing dynasty emperor, which actually is somebody who invaded China. So if we talk about ‘national treasure,’ which nation do we talk about?”

Ai Weiwei sees his use reinterpretation of the ancient zodiac heads as a link in a longer historical chain, observing that the Qing dynasty heads were themselves based on Tang dynasty renderings. At the same time, he notes the ability of the subject to transcend any historical context. For those unaware of this complex story, Ai comments: “They’re just animals… I want this to be seen as an object that doesn’t have a monumental quality, but rather is a funny piece … people can relate to or interpret on many different levels, because everybody has a zodiac connection.”

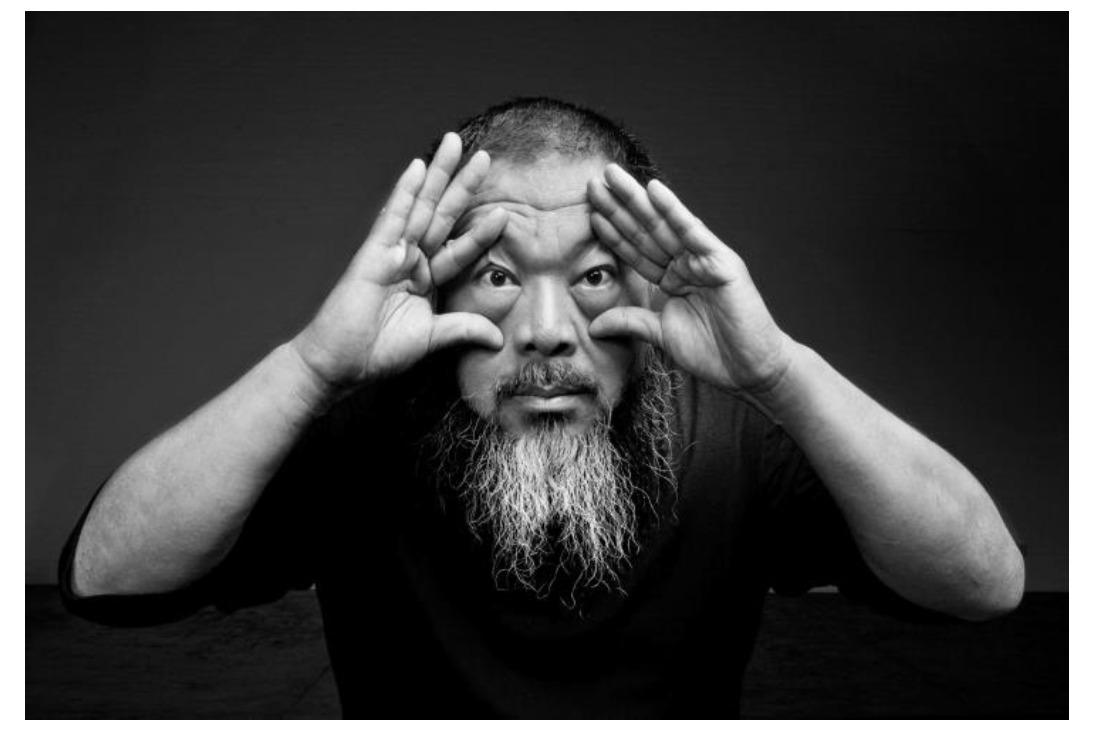

Artist, curator, architectural designer and social activist, Ai Weiwei is perhaps the best-known and most successful contemporary Chinese artist working today. He was born in Beijing in 1957 and is the son of the acclaimed, Ai Qing, one of the country’s finest modernist poets. Ai Qing’s poetry appeared in nearly every literature textbook in China until he was branded a rightist and exiled to the countryside with his family (including his infant son Ai Weiwei) for 19 years. Ai Weiwei’s birthright is simultaneously one of a cultural insider and a political outsider. Growing up in exile laid the groundwork for his future role as an artist-activist and champion for freedom of speech and social justice.

Upon his return to Beijing in 1978, Ai Weiwei became a founding member of The Stars (Xing Xing), one of the first avant-garde art groups in modern-day China. In 1981, he moved to New York where he lived for 10 years and gained attention for his artwork that transformed everyday objects into conceptual works — the notion of the ‘readymade’ as inspired by Marcel Duchamp. Returning to China in 1993, the artist co-founded the Chinese Art Archive & Warehouse, a non-profit gallery in Beijing where he still serves as director.

Ai Weiwei regularly exhibits in major museums and galleries around the world. He worked closely with Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron to design the 2008 National Olympic Stadium (“The Bird’s Nest”). After being allowed to leave China in 2015, he and his family have lived in Berlin, Germany and in Cambridge, UK (his home since 2019) while working and traveling internationally.

LongHouse Reserve is at 133 Hands Creek Road, East Hampton. For more information, visit longhouse.org or zodiacheads.com.