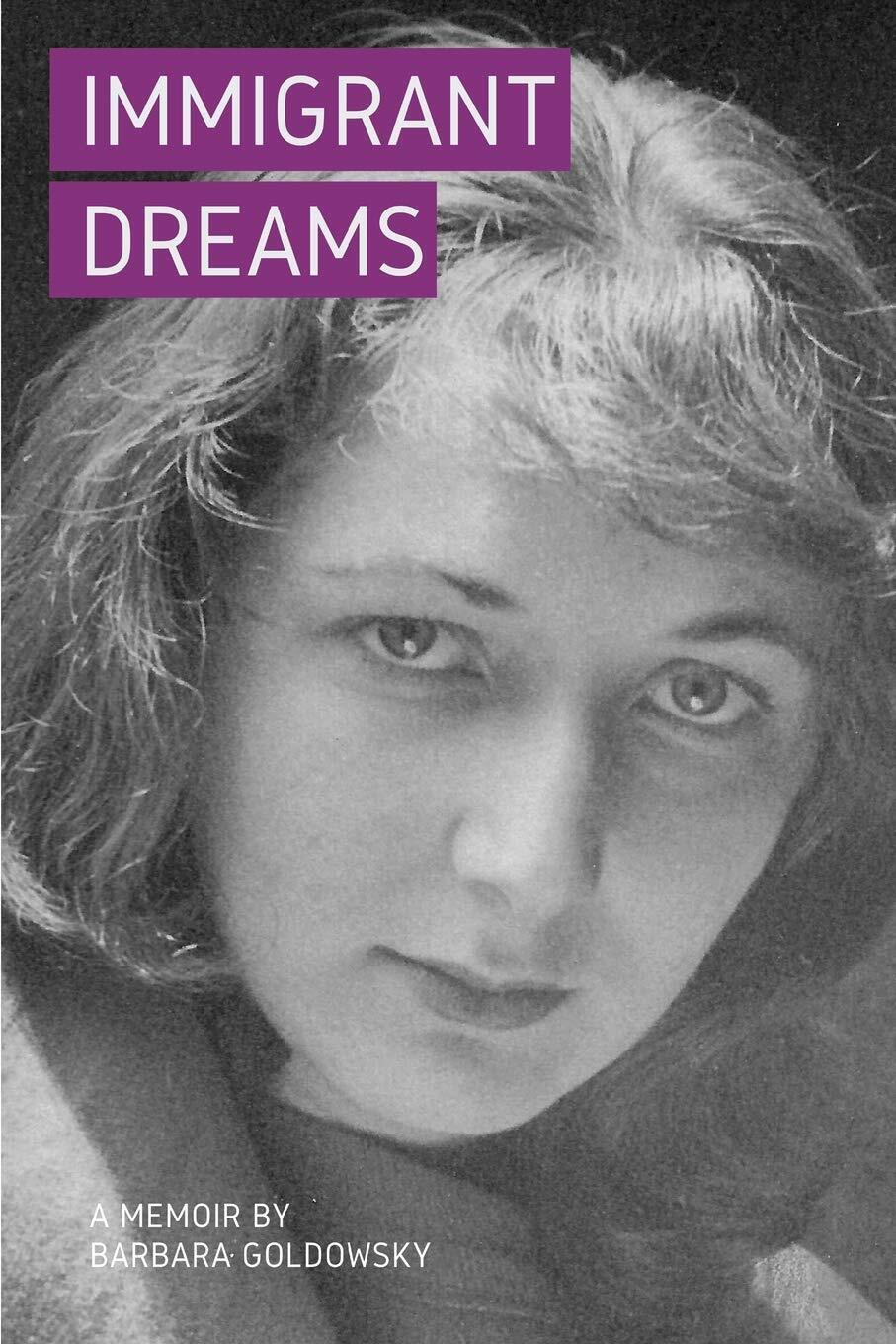

Although she came to this country when she was 14, Barbara Pitschel Goldowsky, now 84, never lost her indomitable heritage growing up in Nazi Germany in the make-do household of a remarkably creative and resilient mother.

The “love child” of a woman who refused to reveal who the father was (“Hans” is all Goldowsky learns about him), in her memoir “Immigrant Dreams,” Goldowsky wonders if he might have been a Jew who would have compromised the “pure Aryan” listing of the family trying to get by. In any case, the pretty blue-eyed young girl was not only deeply loved by her mother but fiercely encouraged by her to endure and persevere. Though “the price for security was silence,” the small family, which included Roland — Goldowsky’s half-brother, five years her junior — managed the trials of living under Hitler’s regime. That included the cruelty and indifference of, and finally abandonment by, Roland’s Nazi-minded father. The family lived in the town of Dachau until they could get a visa to America. Her mother would go through four husbands, none of whom were the author’s father.

It was her mother’s shrewd ability to make and seize opportunity without losing humanity and purpose that stays with Goldowsky as she recounts what it was like growing up during and after the war, her mother taking in a couple of (non-Jewish) survivors from the camp, negotiating the Black Market, and then starting a clothing design business in Chicago where the family settled. They were soon joined by Lincoln, a hometown older artist friend of her mother and eventually, one of Goldowsky’s lovers.

Goldowsky always knew that what she wanted to do was be a journalist. She did well in American public schools, attended a junior college where she studied English and writing and had the good fortune to be mentored by teachers who cared, all the while assisting her mother in the growing clothing business. A clerical stint with the A.P. was significant, introducing her to Sam, an older, savvy reporter based in Washington, D.C. who became a valuable guide (and lover). Intelligent, educated, entrepreneurial, she won a scholarship to the University of Chicago where she earned a B.A in political science and got herself a job on the prestigious literary magazine, The Chicago Review. Always a go-getter, she was never dismissive of entry-level work that might lead to better positions.

The episodes she recalls show how she fulfilled her mother’s hopes for her. Would that more of the memoir, however, have been devoted to her childhood years because of what it might have offered in retrospect about the townspeople of Dachau, including schoolmates. It’s a perspective that would have stood out among the numerous Anne Frank-like recollections that are still being published about those for whom dreams were deferred, or died.

Goldowsky dedicates “Immigrant Dreams” to her mother but augments the theme of hard work with recurring statements of appreciation for those who helped her along the way, including the attention and affection of older men, two of whom she married: the recently divorced Noah Goldowsky (d. 1978) who owned the Holland-Goldowsky Gallery in Chicago, and later the eponymous New York gallery on the Upper East Side, featuring abstract expressionists, and later, as a widow, the polymath inventor and musician Norman Pickering (d. 2015), married at the time they met.

As Noah Goldowsky’s wife, Barbara Goldowsky became a familiar presence in East Hampton where the couple started to summer and then in 1974 bought a house for their growing family, enrolling their two sons in the Hampton day School. There, she became an active volunteer and soon joined the board of directors. She met Norman Pickering when she went to enquire about cello lessons for her younger child, and from there went on to become a significant figure in the art world, helping to found, direct and promote Pianofest in the Hamptons.

Written in a simple narrative style with an eye for recreating dialogue-driven scenes, “Immigrant Dreams” is exemplary of the immigrant experience and the American dream, both now under siege by the current administration. Although the author’s experiences might prove daunting to those who did not have a loving mother bear or helpful contacts borne of intimate relationships, the memoir engages as testimony to pluck and luck. Barbara Goldowsky realized her dreams of becoming a published writer, of prose and poetry. As she looks back to when she started freelancing for The Southampton Press and hosting a local radio program, she reflects, “Dreams do come true. You are one lucky immigrant.”

Indeed.