At 83, Bill “Pushcart Press” Henderson, author, editor, publisher, cancer survivor and late-life grandfather of identical twins, has found renewed pleasure in writing notes for his five-year-old grandsons that he hopes will be of some value to them later on — and also to others who know about his personal and professional trials and triumphs. Friends he’s made in Springs where he’s lived for decades with his wife, writer Genie Chipps Henderson, and also in Maine where he has stubbornly pursued an even more Spartan life with nature and beloved dogs.

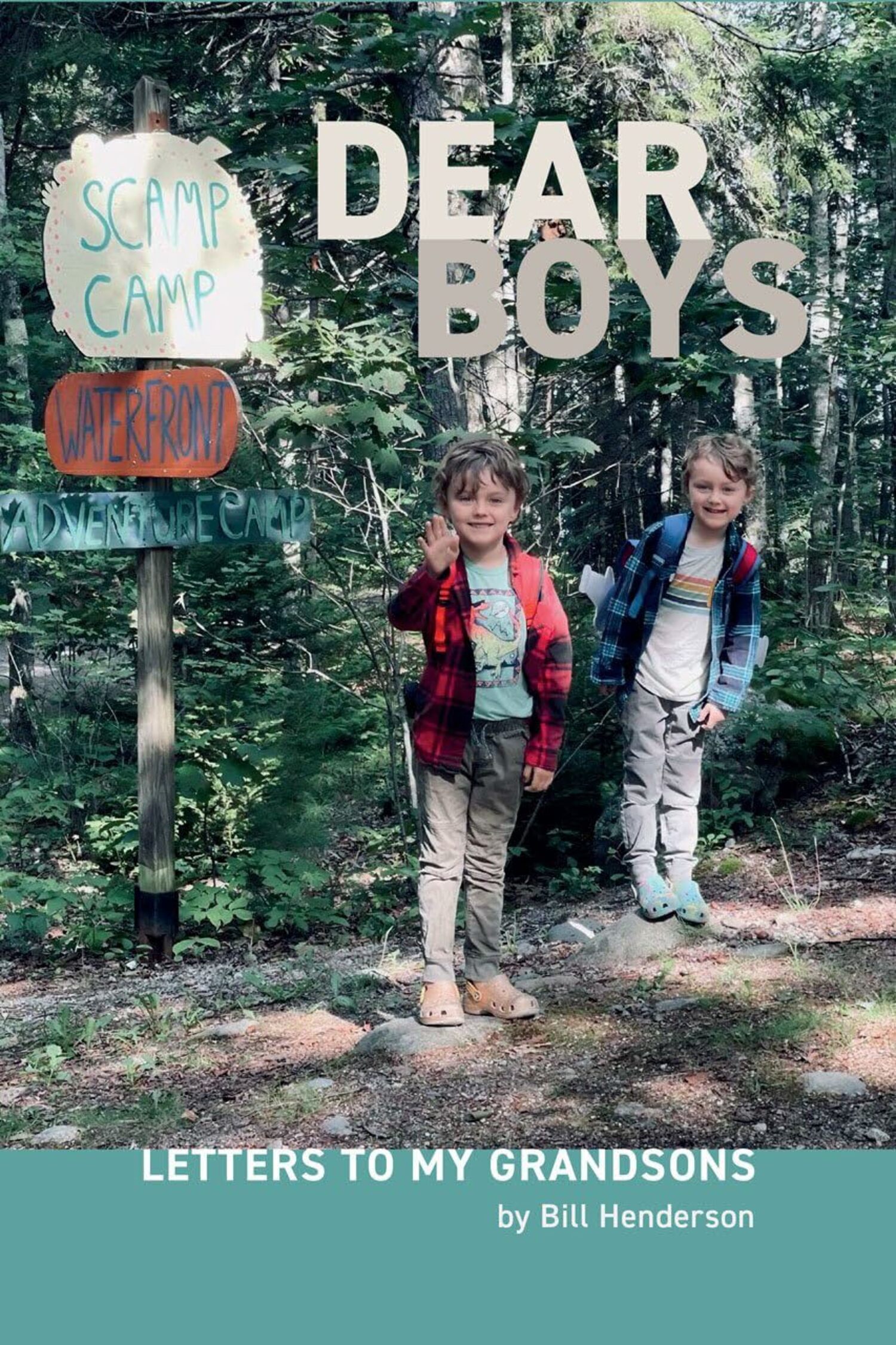

“Dear Boys” — a collection of letters to his grandsons, along with quotable snippets from literature, history and sermons — was originally intended as a kind of family album, but along the way Henderson says that friends urged him to go public with the musings and advice because they might be “useful” to others.

Of course, people writing memoirs usually say that they also write for others, even though they know it’s doubtful that one person’s account of challenges and salvation can guide another through pain, confusion, conflict or resolution. Memoirists are proud of their accomplishments and overcoming difficulties, and want to say so. They knew that few of them would be subjects of biographies, where decisions about significance are made by others. So, for sure, a memoir is an ego trip, but in a context where friends, family and colleagues can be acknowledged, the memoir can help build a sense of community and help to promote a good cause as well as celebrate a way of life. Indeed, what differentiates a memoir from an autobiography is that a memoir selects a theme out of a cradle-to-grave sequence and focuses on something important that burnished a life. In the case of entrepreneurial Bill Henderson, there is, he tells his “boys” no doubt what that something was — and is — and he hopes that it will be his legacy to them: a chosen if not genetic inheritance of the importance of Grace.

Henderson is aware that the boys are barely at reading age. He also knows, however, that they are already subject to undue influences less pervasive and powerful than those that surrounded him in childhood and adolescence: the unstoppable, unfiltered stuff of omnipresent social media. By contrast, he wants to tell his “Dear Boys” about his own past which, for all its “checkered history of self,” was nonetheless free of electronic tyranny and filled with a sense that he was always led by “guidance and grace from an unknown source,” and love. Jesus and St. Frances are invoked often, and his remembrance of things past includes slightly distant but loving church-going parents. He particularly regrets he knew little about his own grandfather and is keen on closing that gap with the boys. In this regard it’s odd that for all the wondrous words bestowed on his and Genie’s daughter Lily, bringer of sweetness and light, he has little to say about the boys’ father, Ed, who gets a quick mention or two. Wouldn’t the boys want to know how their grandfather saw their parents’ marriage? How he sees their father in a nuclear family dedicated to Nature, God and an inheritance of love?

Essential in the collection is Henderson’s constant differentiation of idea and implementation — particularly between institutional religious belief and inner spiritual values. He has a healthy cynicism toward the church’s hypocritical flouting of the values of Christ. Still, he keeps close to childhood memories that provided him with a sense of reverence, justice, decency. And a love of music, especially those of enduring hymns. He acknowledges awkwardness about sex and his succumbing to adolescent temptations, especially alcohol, but he seems fortunate to have escaped drugs. He never descended to need AA, even when his first marriage to Nancy, an ex-nun, ended, but he recommends it. Its theme is his theme: to anchor one’s life in the sacred. How many young men kept their courage up by carrying around an old Chinese proverb in their wallet: “The diamond cannot be polished without friction, nor the man perfected without trial”? For those who know (of) Bill Henderson only through his championing of good writing, some of these revelations may surprise, though not his style. Written with simplicity and directness and a writer’s experience crafting conversational narrative, “Dear Boys” grows into a philosophical cry for Soul, an argument against “the digital colonization of this planet” and a plea for reimagining a “vision of what people are for.”