Even if you don’t know Gahan Wilson’s name, chances are very good that you’ve laughed at his creations.

As one of the most legendary cartoonists of the last half century, his work appeared often in magazines like Playboy, and in National Lampoon, where his regular comic strip, “Nuts,” delved into the world of childhood trauma.

Blessed with a cunning sense of humor and a wry — if somewhat warped — world view, Wilson was also a frequent contributor to The New Yorker, both inside and out, and many of his illustrations graced the cover of that magazine over the years.

And though internationally acclaimed for his artistic talents, for more than two decades Wilson lived a quiet life in Sag Harbor, where he was a regular fixture in the village. Because he didn’t own a car, many people knew Wilson by sight as he walked to and from Main Street from his home, often accompanied by his wife, novelist Nancy Winters, who lived primarily in London.

But in recent years, life has gotten much more difficult for Wilson.

Now 89, he suffers from advanced dementia and other health issues. Nancy Winters, his wife of 53 years, died on March 2. He no longer lives in Sag Harbor but is currently in Arizona, where his stepson, Paul Winters, is assisting him as he navigates his new reality.

To that end, Winters is working hard to raise the funds necessary for his stepfather’s advanced medical needs through a GoFundMe campaign titled “Help Gahan Wilson find his way.”

“Here is a saying,” reads one entry on Wilson’s page, “How do you make God laugh? … Tell him your plans.”

Winters is a director of photography with his own independent film company, and in a recent interview he said that, initially, those plans had been to move his mother and stepfather from New York to the ranch he and his wife, Patty, own outside Phoenix.

He explained that his parents left Sag Harbor about five years ago and moved to New York City, where they settled into an apartment in Greenwich Village.

“I talked to Gahan all the time,” said Winters. “He absolutely loved Sag Harbor, the people and the nuance of the place.”

From Winters’s vantage point in Arizona, for a while everything seemed fine in the city, too, with his mother caring for Wilson as his dementia began to set in. At least, that’s what he was led to believe during regular conversations with his mother.

“On the phone, she would say, ‘We’re in the middle of a wash — if you let it dry out, you can’t go back,’" said Winters, referring to Wilson's process of creating his watercolor cartoons. "Or she’d talk about Patty, my wife and Sag Harbor. They weren’t in-depth talks.”

Ultimately, as is often the case for adult children who live far from aging parents, it was decided that the elderly couple needed to come live with Winters and his wife in Arizona. But when they did, it quickly became apparent to Winters that his mother and stepfather were not nearly as fine as he had thought.

“At what point does a child step in when they have Alzheimer’s and don’t want help?” asked Winters. “She was supposed to be watching the eggs in the hen house. But she had it too and was so good at disguising it. It took me a month before I realized it: My mother was covering for herself and him.

“At the end, they didn’t make good financial decisions. When they showed up, they had two empty suitcases and no money,” Winters added. “They lived at our house for a while, then Gahan got sick and started wandering. We’re on a ranch that leads out into the desert, and it’s 60 miles of saguaro cacti. We were afraid for his safety.

“They reached a point where they needed help,” he said. “I didn’t want to be the guy who restrained my stepfather.”

So Winters moved his parents into an assisted living apartment nearby, where they had their privacy but also the help they needed. It seemed the ideal situation.

“It was a lovely place. We’d bring her wine, and she was happy,” said Winters. “But Mom always pointed to the memory care people behind the fences and said, ‘You don’t want to end up there.’”

In March, when Nancy Winters died, it was obvious that the memory care facility was exactly where Wilson now needed to be.

“She was his rock,” Winters noted. “While we all helped with his care, it was my mother who grounded him … She was his guide at the end.”

Her death not only drastically changed Wilson’s living situation, it also altered his financial picture for the worse. “When my mother died, they immediately took him off state aid, saying he makes too much on his own,” added Winters, who realized that after the IRS took its share, there was not enough money left to care for his stepfather’s advanced dementia going forward.

“If you’re middle class, your family is going to pay for it,” he said. “No one plans for it.”

That’s why Winters started the GoFundMe account. Since last spring, it has been collecting money for Wilson’s care. To date, $80,600 of the $100,000 goal has been raised through friends, acquaintances and longtime fans of Wilson’s work.

While Winters notes that Wilson has had some major health setbacks recently, including a fall, a serious surgery, and uncertainty about his ability to return to his former memory care facility after a hospital stay, he notes that his stepfather remains remarkably upbeat.

“Being humorous helps. He knows he’s Gahan Wilson, he can talk Matisse and Picasso but can’t remember where he is,” said Winters. “I’m 65, I’ve known him since I was 10, and when I ask him who I am, he doesn’t remember. He says, ‘I don’t know, but you look like someone important to me.’”

Now, as Wilson approaches the end of his journey, in many ways, so, too, does his art form, as print magazines morph into something new, go digital or close up shop altogether.

“Playboy is done and is not what it was. Soon, The New Yorker will have to go digital,” Winters predicted. “Gahan would say, ‘What will happen to us?’ He saw there would be no more magazines. I don’t think the art of cartooning has transferred to the internet. A meme is a cartoon these days.”

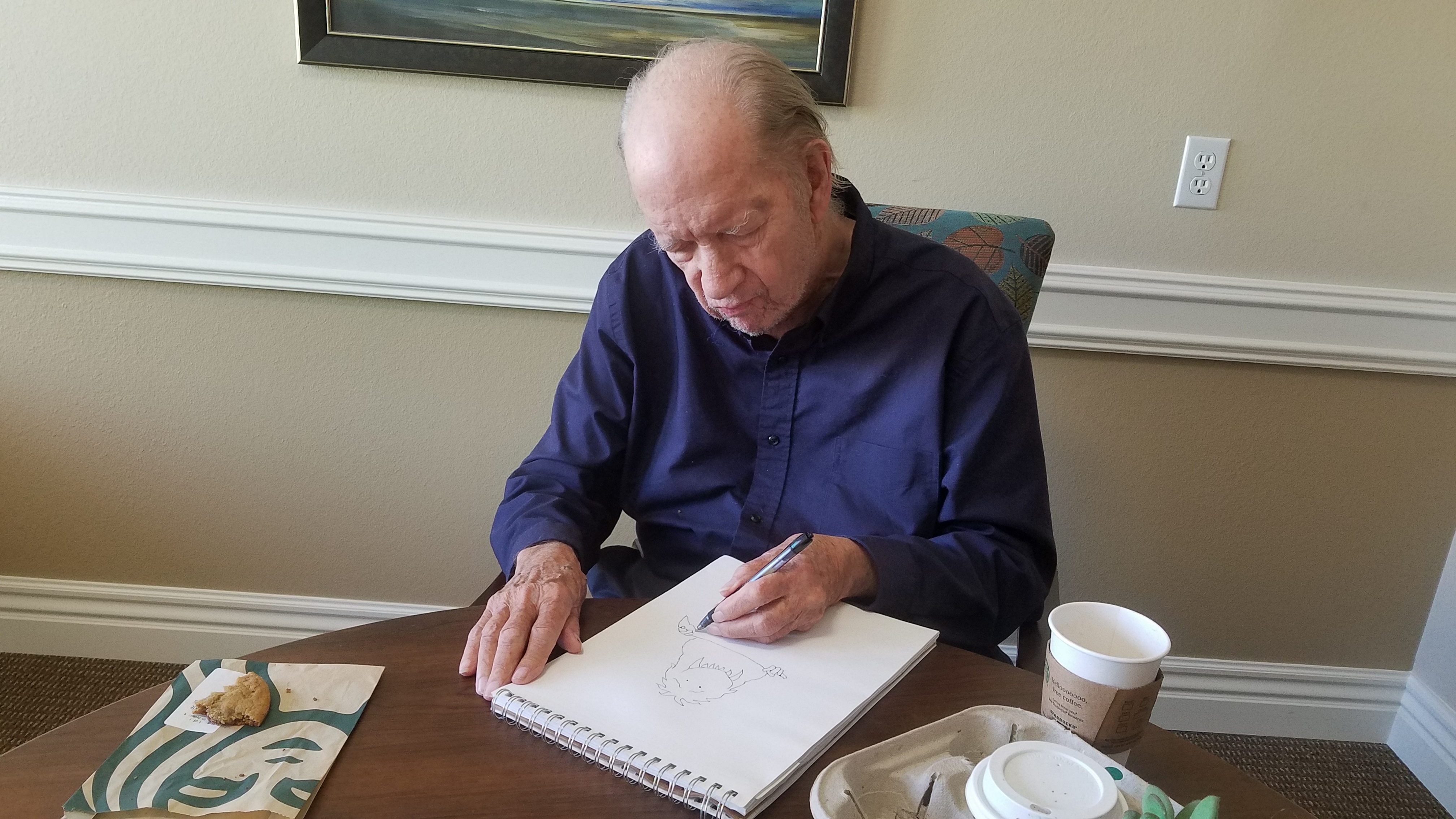

But that doesn’t mean Wilson has totally given up on art. Like a primal instinct that refuses to succumb to life’s changes, Winters reports that Wilson still draws from time to time, but now, his cartoons have no words to go with them.

“He’ll sit down and draw for about four minutes. But the days of Gahan doing a full-color finish with crosshatch and watercolor are over,” said Winters. “When he first moved out here, I bought him an easel, paints and canvas, and it upset him. It was a challenge. Then I gave him a pad of paper, and that was OK.

“He doesn’t draw much, but when he does, it’s very small. He recently drew a monster holding a sign that says: ‘Glad to remain alive.’”

On top of his physical challenges which have diminished his artistic ability, Wilson is also struggling to understand where his wife has gone. “He kept asking, ‘Where’s Nancy?’ I told him one time that his wife died, and for a moment he came out of the dementia and said, ‘That makes sense, thanks for telling me.’ Then he forgot.”

As his condition worsens, it’s almost as if Winters is witnessing his stepfather’s persona revert to that of the young child he once was, full of wonder and excitement at rediscovering the world.

“Every time he sees something, it’s new. He’ll go and look out the window as if he were a 5-year-old and say, ‘Look at those mountains!’” said Winters, who feels that Wilson’s resiliency can be traced to the fact that, ultimately, he has always been an expert in the human condition, and throughout his career explored what that means on a universal level.

“He makes you pull back the curtain. He says there’s more. I know all his doctor and hospital cartoons and every eventuality, including this — losing his faculties,” Winters said. “He has one cartoon where a guy asks, ‘Where is everyone going?’ And all of them are falling naked through the hourglass, going down with the sand.”

In recent weeks, Wilson’s situation has changed once again. After two hospital visits, he was sent to hospice and was not expected to survive. But he made an amazing recovery and now lives in a group home with a higher level of care than his previous facility. This one is just 10 minutes from Winters’s home, so he is able to visit Wilson frequently.

These days, Winters has time to recall the many years he has enjoyed with his stepfather. He says that one of his fondest childhood memories is of a day when he and Wilson traveled to the city together on the train from Connecticut. It was a workday, so all the businessmen had their briefcases, which they hung on the hooks above their seats.

“When we came aboard, we got two seats, and Gahan pulled out a rubber fish with a hook and a line and hung it on the hook where the briefcases went,” Winters recalled. “We sat down and he didn’t say anything else about it.”

It’s that kind of quirky humor that has always made Winters love and appreciate Wilson — just as his legions of fans have done over the years.

“I used to tell Gahan that most people didn’t know what he looked like. We’d go buy books, he’d hand over his Amex, and the employee would say, ‘Holy shit, you’re Gahan Wilson! … Let me tell you my favorite cartoon …’”

“Now it’s happening. All those people are saying how much he meant to them,” said Winters. “What I notice about the GoFundMe is he’s touched so many people who said thanks for helping shape my outlook on life. You’re a living legend and a natural treasure. Then they’ll donate $1, $4 ... They’re making life better for us.”

To “Help Gahan Wilson find his way,” visit his page on GoFundMe.com.