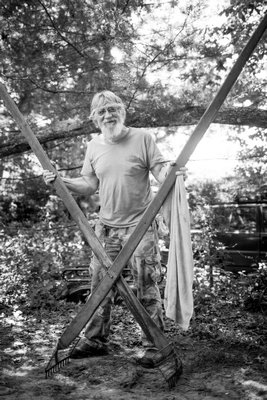

Albert Lester’s clam rakes have attracted a lot of attention lately.

Three years ago, I worked on a story about Mr. Lester’s large collection of antique and custom-made clam rakes with Edible East End magazine’s photo editor, Lindsay Morris. Ms. Morris’s photos turned out so well, she went back for another round after the story was printed.

Mr. Lester couldn’t bear for the rakes to leave his property, so Ms. Morris photographed them on a canvas sheet on the ground, gaining height from a ladder. In her studio, she painstakingly Photoshopped any debris out of the photos. The results are simple yet astounding and can be viewed at the Bridgehampton Inn Restaurant throughout the summer.

I took Mr. Lester to the opening reception of “Sea Rakes” last Thursday, June 15. The evening felt natural and organic. Mr. Lester’s clam rakes were elevated to works of art that fit seamlessly into the restaurant. Originally built in 1795, the space is now updated with orange chairs and roses in the garden to match.

“I can’t believe they’re photographs,” said Ami Ayre, admiring the show which moved through the three dining areas, each equipped with a fireplace and tables set with hand-blown water glasses with orange swirls.

By removing the background in the photograph, the clam rakes seem to be floating in space. “I wanted them to pop,” said Ms. Morris, “which gives them that illustrated quality.”

Eel rakes, donated to the Bridgehampton Museum by a regular diner at the restaurant, accompany the clam rake photographs on the wall. The exhibition was hung by Gerrit van Kempen, who fashioned secure holders for the very spiky rake heads.

The van Kempen family runs the Bridgehampton Inn and Restaurant, as well as Loaves and Fishes Food Store and Cookshop, with Sybille van Kempen at the helm.

She hopes, by decorating the restaurant walls with clam rakes and eel spears, people will start a conversation, creating a greater awareness of history and what it’s really like to live on the East End. “People hear about it but don’t get to see it,” Ms. van Kempen said. “I want to share something of the community with the community.”

Mixologist Kyle Fengler, Ms. van Kempen’s son, shared his “Honeymoon Punch.” Little did he know, Ms. Morris and her husband, Stephen Munshin, were celebrating their 21st wedding anniversary that evening.

Lemon verbena leaves were frozen into huge ice cubes that kept Mr. Fengler’s golden Applejack-based cocktail chilled in a clear bowl. “Applejack is one of the oldest, if not the oldest, distilled spirits in America,” Mr. Fengler told me. Fitting, since some of the rakes date back to the 1600s.

“It’s really the combination of the old and new,” Ms. van Kempen said of the allure of the photographs. “We do that here at the inn.”

As mini crab cakes and lamb kabobs were passed around to guests, I couldn’t help but feel a sense of pride in my friends and my community. The night made me realize why I love my job as a writer so much. A story doesn’t always jump off the page in such a grand fashion.

In the meantime, last fall, Gef Flimlin read the story online and decided he had to meet Mr. Lester. The recently retired Rutgers Cooperative Extension marine agent spent his life teaching people why it’s important to protect our bays through his aquaculture classes. He’s an active member of the East Coast Shellfish Growers Association as well as ReClam the Bay, based in Barnegat Bay, New Jersey, where he lives. In his spare time, he travels up and down the East Coast talking to longtime baymen.

There are not a lot of places that still have a large number of full-time clammers. “There are a few on Long Island, some in Rhode Island, and some in Raritan and Sandy Hook bays,” Mr. Flimlin told me. “But the days when a kid could go into Great South Bay or Barnegat Bay to harvest clams all summer long and pay for his college tuition are gone, to our, and the bay’s, detriment.”

Mr. Lester continues the tradition of generations of clammers who made a living on the water. “He and they are astute observers and keep small bits of information about where the good spots to clam are, and how the weather affects the bay,” Mr. Flimlin said. “They become protective of that marine environment and cherish what it provides. They gather things that they find and hold them as dear because it reminds them of the pleasure they get from being in nature and harvesting good food for people to enjoy.”

The history of the clam rakes in Mr. Lester’s collection can be traced from John Fordham’s original eagle claw, which he inherited from his grandfather, to his customized T-bar, which attaches to his waist, and helps, not hurts, his back.

“These tools show a progression of need. They show that the clams and oysters have always been a food that people liked and wanted,” Mr. Flimlin said.

Not only were the clams eaten, but the purple color inside the shells was deemed so valuable, the shells were used as currency. “The Latin name for the hard clam is Mercenaria mercenaria, which indicates a use as money,” Mr. Flimlin noted. “The color also lent itself to being carved and used as jewelry.”

It’s yet another tradition Mr. Lester has carried on, carving his first piece of wampum into a unicorn, for his daughter. He has since learned to stay away from delicate appendages in his designs.

“As far as rake design goes, they are all essentially an evolution of a hand or hands grabbing shellfish from the bottom of the bay,” Mr. Flimlin said.

For Mr. Lester, the clam rakes are more than tools, and even more than works of art. “They are a big part of my family’s heritage,” he said after the show. “They remind me where I came from. My ancestors didn’t have a job to go to—they lived off the land and the sea.”