For Chris Hegedus, standing alongside James Carville and George Stephanopoulos in the war room when Bill Clinton was elected president of the United States was one of the highlights of her career — but her excitement was not necessarily for the candidate himself.

It was primarily for Carville and Stephanopoulos, the masterminds behind the 1992 campaign that would forever change the face of politics — cementing the film she made about them, “The War Room,” in documentary history, shared alongside her partner in life and film, DA Pennebaker.

And while this moment was, undoubtedly, also a career high for the groundbreaking filmmaker, who often went by “Penny,” he told The Guardian in 2013 that another topped his list: when Hegedus had walked through his door 37 years earlier, looking for a job.

“He was my biggest cheerleader and I miss that,” Hegedus said during a recent telephone interview. “I miss his encouragement and his passion for film, for storytelling.”

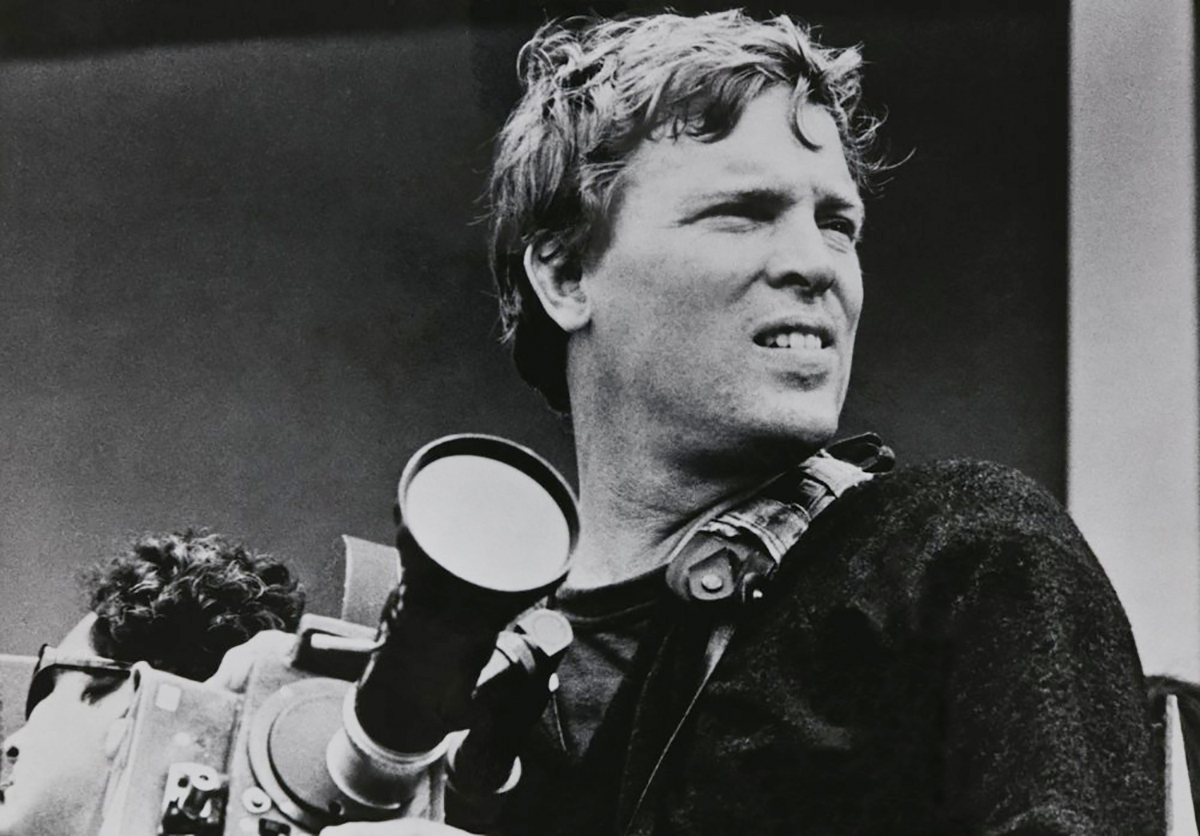

On August 3, Pennebaker died at age 94 at home in Sag Harbor, leaving behind a legacy that includes dozens of cinéma vérité documentaries, notably “Dont Look Back,” “Monterey Pop” and, of course, “The War Room,” which will screen on Saturday, December 7, at the Southampton Arts Center, as part of the 12th annual Hamptons Doc Fest.

But, perhaps more important, Pennebaker was part of a team that helped redefine what documentary filmmaking means. And the festival’s inaugural Pennebaker Career Achievement Award — to be presented to director Robert Kenner on Saturday, December 7, at Bay Street Theater — will always represent that, Hegedus said.

“For me, it’s honoring Penny’s groundbreaking contribution to moviemaking,” Hegedus said of the award. “He was part of a group of filmmakers that engineered the first sync-sound portable camera system that enabled you to follow the drama that was happening in real life, as it happens — something that we take for granted today, when we can film everything on our phones.

“It really began the first storytelling in documentaries that was a lot like fiction films — where they had storylines that had beginning, middle and end, and crises, and whatever you would find in a Hollywood film, especially really passionate characters to follow.”

While synchronous-sound cameras are far from a precious commodity today, they were an unimaginable technology until the 1960s, when Pennebaker — who served as an engineer in the Naval Air Corps during World War II — linked up with pioneering filmmakers Albert Maysles, Richard Leacock and Robert Drew to re-imagine what was possible.

Together, they built a camera that allowed the cinéma vérité movement to take shape, freeing up filmmakers to move with and among their subjects, ultimately doing away with the postproduction voice-over narrative model that was commonplace up until this point.

It was in search of one of these new cameras that Hegedus first met Pennebaker.

“I was looking for a job, specifically, that had one of these sync-sound cameras,” she recalled. “At the time, they were very expensive and there weren’t a lot of them around, so if you wanted to shoot films — which I was doing before in a job that I had, but it was more of a commercial job — you had to have this equipment.”

First she approached Drew, who pointed her up the street toward Pennebaker, she said. He immediately struck her as charming and a natural conversationalist, she said, even despite the current circumstances.

“At the time I went to see Penny, he was going bankrupt,” she said. “So I came in at a time when he was struggling, and he was really looking for a partner. I guess it was kismet, that I just happened to come and have very similar ideas about the kind of movies that I wanted to make and the type of movies that he was making.”

In their early years together, the duo did not have the luxury of being “choosy” when it came to documentaries, Hegedus said. They relied on sources with access and funding, she said, “but one of the films that we always wanted to do was about a man running for president.”

In a roundabout way, the opportunity would present itself via co-producers R.J. Cutler and Wendy Ettinger, who pitched a related idea to Pennebaker and Hegedus. They suggested a film on the behind-the-scenes campaign of the young Arkansas governor running for president, largely in part because direct access was denied.

“He already had a photojournalist and a journalist, so we were relegated to the campaign staff — which I always thought of, at first, as a booby prize because if Clinton lost the election, we’d have a totally unsellable film about the losing staff of the losing candidate,” Hegedus said. “But those are the kinds of risks you take when you make a real-life story about something. It doesn’t always turn out as you think.”

The decision turned out to be a fortuitous one, because the fast-paced, energetic inner-workings of what would become known as “the war room” were nothing less than brilliant and utterly captivating — though Hegedus didn’t fully realize it until outside the editing room.

“I thought it was a little of a downer because we didn’t film the candidate, and it was only really after I made the film and showed it at the Toronto Film Festival that I realized that, of course, none of the journalists and critics that were writing about the film had been in the war room,” she said. “They were only watching what you get to see if you’re a journalist, which is like, the candidate goes in the hotel and out of the hotel, and they don’t really get to see the process and the people who are behind him.

“They were fascinated by it and it was really only then that I realized that this was a film that was gonna have some legs.”

As a two-person crew, Pennebaker would typically shoot video while Hegedus took sound — “mostly because Penny was not a good sound-taker; he was always moving his hands around the mic, making lots of noise,” she recalled with a laugh — before coming together in the editing room.

“I would usually edit the film down to a few hours, and then Penny would come in and we would both edit the film, and we would usually get divorced during this process,” she said laughing again, “because it’s the creative part of the process and everyone has their own opinion on things. That’s much more of an artistic struggle. I think because we respected each other, we somehow made it through all of those films, and we remained lovers and friends and partners.”

Their 43-year filmmaking partnership, which saw some four-dozen documentaries together, was made only stronger by their marriage, Hegedus said.

“Documentaries, when you’re dropped into somebody else’s world, you get very immersed in it, and sometimes these films take a long time,” she said. “To be able to share that with your life partner is really special, and it’s something that I think bonds you. I feel very fortunate to have had that situation.”

Striking out on her own, Hegedus said she feels the void in “too many ways to probably mention,” but she is keeping busy as a producer, while searching for a home for their immense archive, which not includes not only their films, but also the vintage camera equipment for which Pennebaker made his name.

In the meantime, Hegedus said she will take with her all of the lessons she learned from Pennebaker, as will the generations of filmmakers who come after them.

“What so many people wrote to me when Penny died was just how much he helped them, how much he inspired them, how he took the time to actually talk to them about their films,” she said. “He was just very democratic in his way that he gave himself to people — for encouragement or advice or whatever they were searching for.”

For more information about the Hamptons Doc Fest, which runs from Thursday, December 5, through Monday, December 9, at Bay Street Theater in Sag Harbor and Southampton Arts Center, visit hamptonsdocfest.com.