Growing up in Buffalo, Peter Yost had a relatively conventional childhood. He would even go so far as to call it boring, especially when compared to that of his friend, Michael Rohatyn.

It came up casually, Yost recalled last week, that in the middle of the night, a helicopter landed on his lawn and the then governor of New York, Hugh Carey, jumped out.

Rohatyn corrected a few embellishments.

“It wasn’t at night,” he said.

“It wasn’t?” Yost asked.

“No,” he said. “They don’t land helicopters in fields at night, except in theaters of war.”

“Or, unless it’s really desperate, Michael,” Yost said.

In actuality, it was desperate. Despite the helicopter landing in broad daylight, in a field adjacent to the Rohatyn family’s East Hampton summer rental, the governor was there on emergency business to meet with the 12-year-old boy’s father, Felix, who was a banker and chairman of the Municipal Assistance Corporation.

It was the middle of the summer of 1975, the year that New York City found itself on the brink of bankruptcy — an extraordinary, overlooked episode in urban American history that Michael Rohatyn watched from the front lines, one defined by greed, incompetence, ambitious social policy, poor governance and, in the end, compromise and teamwork.

All the makings of a great film, Rohatyn — who is a screenwriter and musician — and Yost, an Emmy Award-nominated filmmaker, agreed.

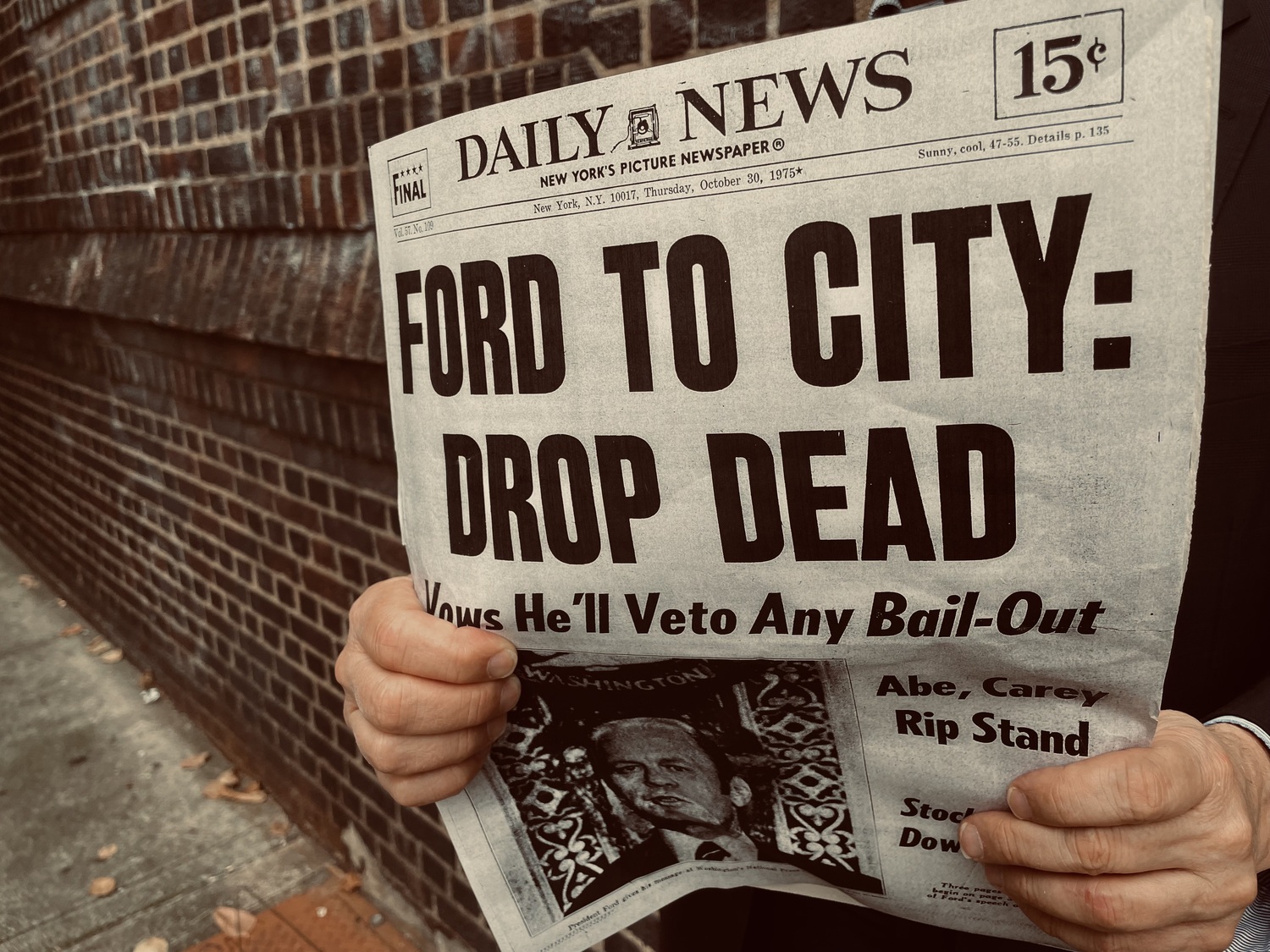

Nine years ago, they embarked on an ambitious project to direct and produce the first-ever feature documentary that captures this era. The result, “Drop Dead City” — which won the Library of Congress Lavine/Ken Burns Prize and closed the 2024 NYC DOC — will screen on Friday at the Sag Harbor Cinema.

A Q&A with the co-directors and former Sag Harbor Mayor Jim Larocca, who at the time was an economic advisor of Carey, will follow.

“It was well known in New York politics, business, civic life that the city was stretched thin, that it was not well managed from a fiscal point of view, but it was sort of a given,” Larocca said. “That it degenerated into a full-blown crisis and the loss of credit standing — basically, the largest city in history of the United States to ever face that outcome — didn’t surprise a lot of people in the know, but it surprised everybody else.”

The story begins in January 1975 with the election of two first-timers: New York City Mayor Abe Beame and Carey. Within weeks, their worlds came crashing down. The city was on the verge of defaulting on hundreds of millions of dollars in bonds and loans — and would soon run out of cash altogether.

And if that wasn’t enough, the city had cooked its books, and its accountants had no idea how much money was in the bank, how much was owed, or how much they would need to borrow.

“The city was, while not legally bankrupt, on the road to a de facto bankruptcy triggered by its inability to pay debt that was due,” Larocca explained. “So once the city started punting its debt and it needed the debt money to meet the payroll next month, the crisis was on in full.

“And then it all was presented to Governor Carey literally as he came through the door on New Year’s Eve, the beginning of 1975 to become governor of New York,” he continued. “That was what was waiting on his desk.”

Over the course of the next few months, firehouses and public hospitals were closed, schools were shuttered, garbage piled up, rioting cops shut down the Brooklyn Bridge, and parts of the city burned. One fire company in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn responded to 10,000 calls in that one year.

Next came a fight for survival — bringing together unions, banks, politicians and state and local institutions in an unlikely alliance. A combination of fixers and flexers, big shots, heroes, cowards and the people of New York City staved off an economic disaster.

“Today, there’s a manufactured crisis that’s being used as an excuse to dismantle whole departments in our federal administrative state,” Rohatyn said, “and in this film, there was a real crisis, and we show what people in the most disputatious city in the world did to preserve their public institutions.”

The documentary features just shy of 40 interviews and they all proved to be admirable and simply great characters, the co-directors said — “even if they were avaricious, self-interested, selfish people, like we all are,” Yost said. Harrison Golden, who was the New York City comptroller in 1975, struck him as clever, smart and political, and granted the team an exhaustive, hours-long interview.

At the end, Golden walked them to the elevator and, as the doors opened, put his arm around each of them and said, “Good luck with it. If you keep at this thing, come back again sometime and I’ll tell you what really happened,” Yost recalled.

“And then we stepped onto the elevator and that was it,” he said. “I think he was actually quite truthful.”

“Oh, totally,” Rohatyn said. “And by the way, he watched the movie not many weeks before he passed away, which was this year, and it was very gratifying. One of the most gratifying things in this, for me, has been showing it to these people that we want to honor, and having them like it and feel really good about it.”

The film also plays tribute to New York itself — a place for invention and reinvention, one that symbolizes an unachievable dream, embodying what the United States can and should strive for, Yost said.

“At the core, it’s a movie about the city, of course, and the people, but also the ideas that animated them,” he said. “We’re getting hugs and people coming up to us all the time. I just went to move my car and our neighbor had just seen it, and she’s lived on our block for many decades in Brooklyn. She was crying, and she just hugged me, and she just said, ‘Thank you.’”

“Drop Dead City,” the first-ever documentary about the New York City fiscal crisis of 1975, will screen on Friday, June 6, at 6 p.m. at the Sag Harbor Cinema. The Q&A follows. For more information, visit sagharborcinema.org. Sag Harbor Cinema is at 90 Main Street in Sag Harbor.