A few weeks ago, literally at the crack of dawn, an intrepid group assembled at LongHouse Reserve for an excursion to the Glass House and Grace Farms in New Canaan, Connecticut. Both sites are notable for their transparent architecture, but the concept behind each is very different. One was designed as a private residence, while the other was conceived as a public space where visitors can “experience nature, encounter the arts, pursue justice, foster community, and explore faith.”

Set in 80 acres of meadows and woodland, Grace Farms was established in 2009 by Sharon Prince and her husband Robert, a hedge fund executive. Their non-profit foundation sponsors meetings, lectures, performances, social justice initiatives and faith-based programs, as well as events organized by outside groups, in what amounts to acombination community center, conference venue, and nature preserve. The price tag was reported to be $120 million.

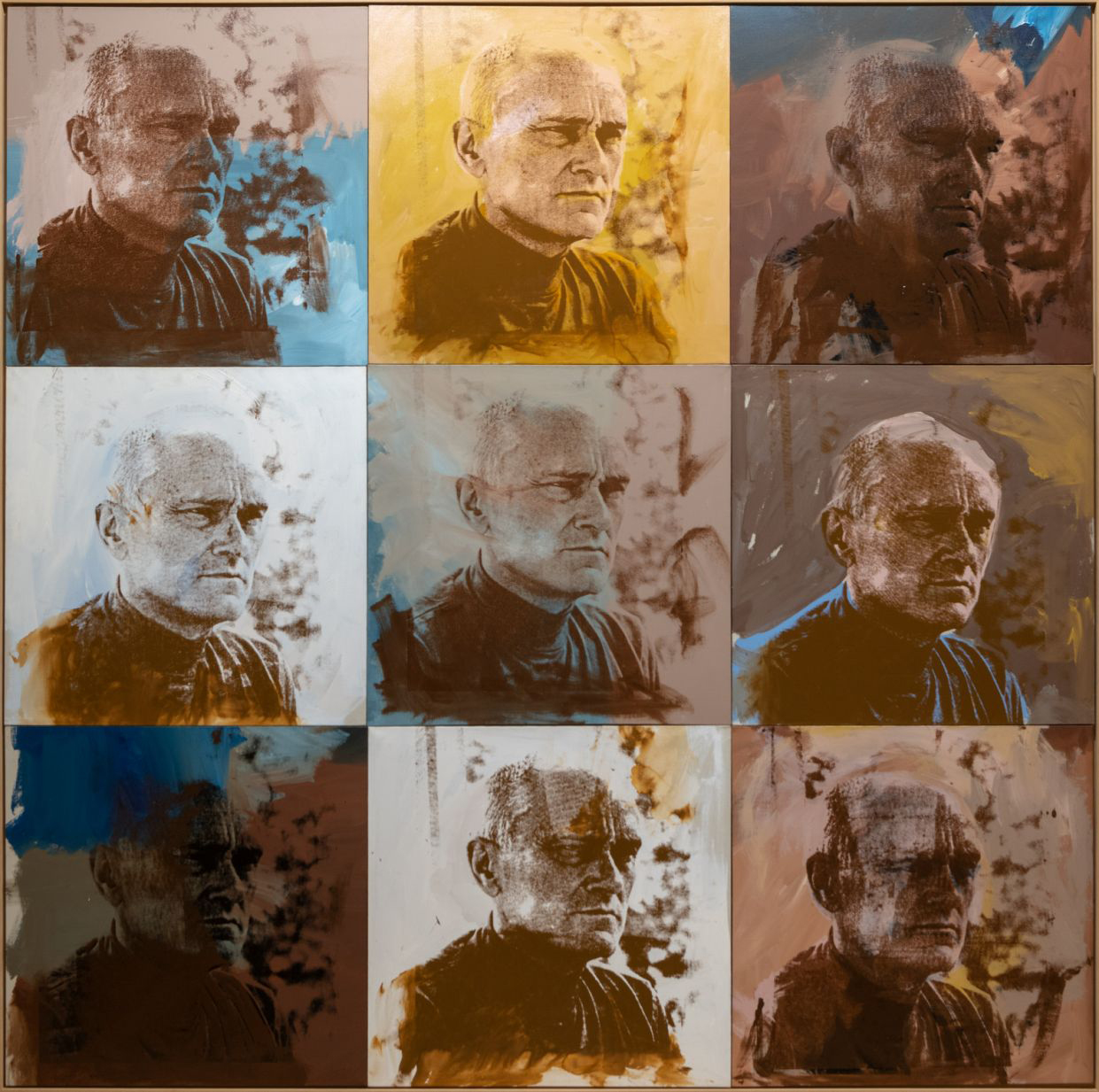

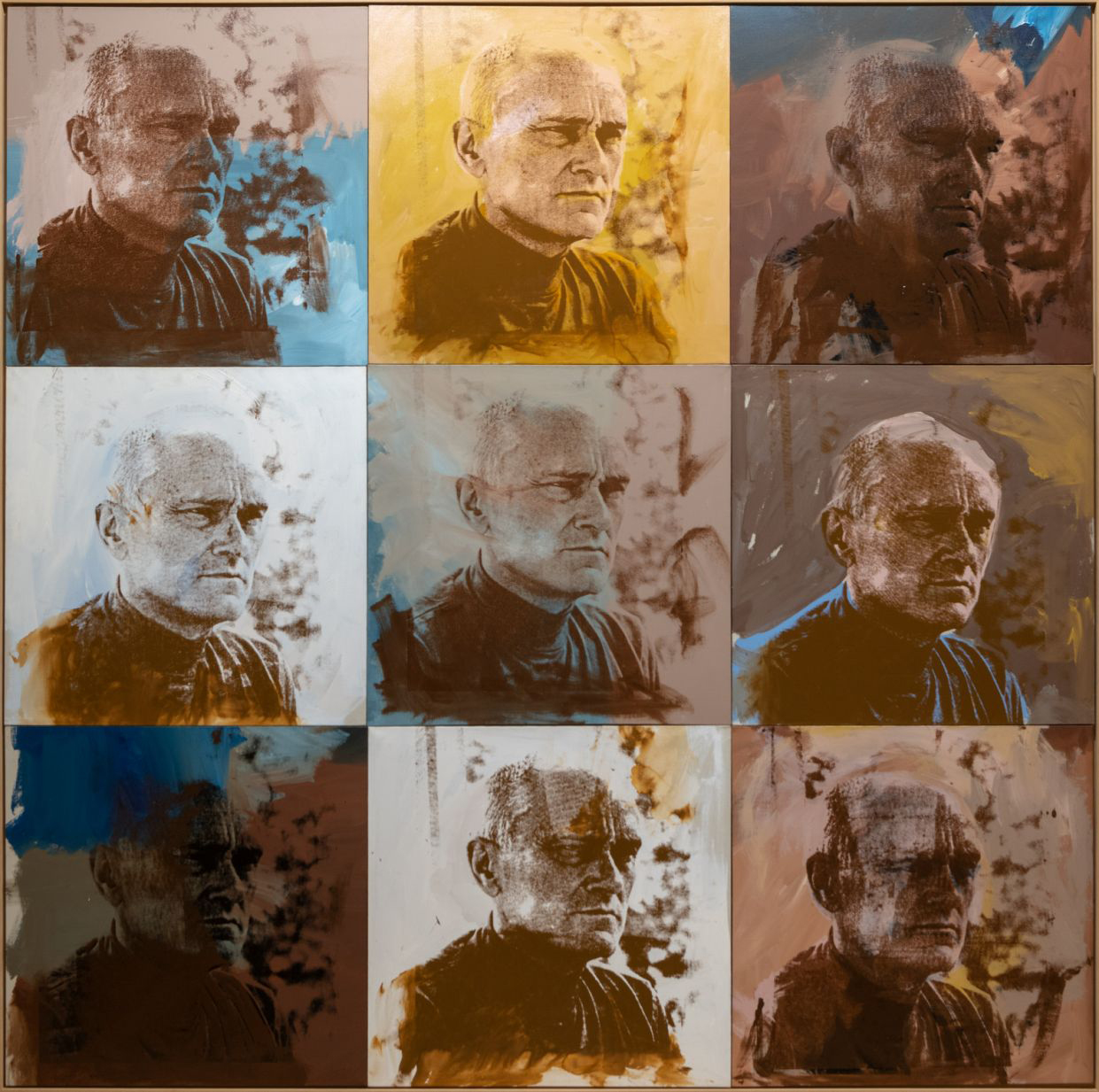

[caption id="attachment_97155" align="alignright" width="300"] Andy Warhol, “Philip Johnson,” 1972. Acrylic and silkscreen inks on canvas, 96 x 96 inches.[/caption]

Andy Warhol, “Philip Johnson,” 1972. Acrylic and silkscreen inks on canvas, 96 x 96 inches.[/caption]

The site is open to the public free, six days a week. Its primary attraction, designed by the Japanese firm SANAA, is a meandering 1,400-foot long building, known as the River, which opened in 2015. Under a continuous aluminum roof, glass walls enclose various activity areas, including an auditorium, library, gym and cafeteria. Our group happened to be there on a glorious fall day. The sky was cloudless, the temperature was comfortable, and the outdoor and indoor spaces complemented each other as intended. The effect is quite spectacular.

The River’s seamless integration of interior and exterior environments is also true of Philip Johnson’s Glass House, which predates Grace Farms by some 65 years. Built in 1949 and based on an earlier design by Mies van der Rohe, the Glass House and its opaque companion, the Brick House, are set well back from the road on a 49-acre site. Visitors need to register for tours and take a van from a reception center in downtown New Canaan.

There are 14 buildings on the property, ranging from a couple of vernacular structures to Da Monsta, Johnson’s final addition, a 1995 whimsy suggested by a Frank Stella design — another illustration of the architect’s magpie sensibility. His close connection to visual artists is illustrated in separate buildings for the paintings and sculpture he collected with his life partner, the curator and art dealer David Whitney (no relation to Gertrude Whitney, founder of the eponymous museum). Their involvement with several other art-world homosexual men who spent time at the Glass House, including Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Lincoln Kirstein and Merce Cunningham, is explored in an exhibition, “Gay Gatherings,” on view in Da Monsta and the Painting Gallery through December 15.

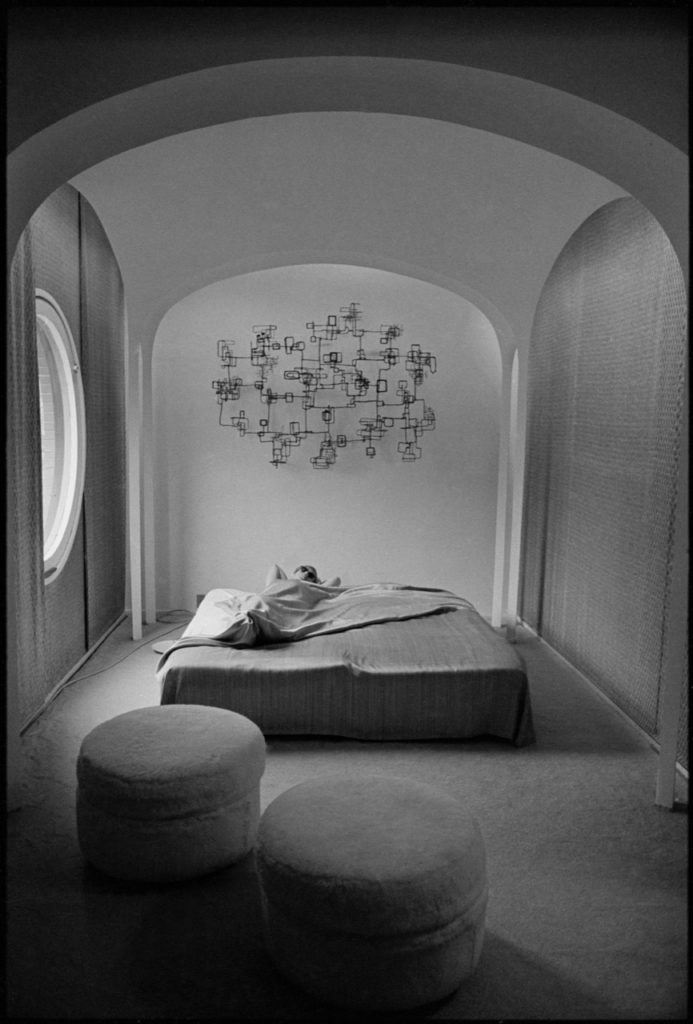

[caption id="attachment_97156" align="alignleft" width="203"] Andy Warhol in bed in the Brick House, winter 1964-65. Photograph by David McCabe.[/caption]

Andy Warhol in bed in the Brick House, winter 1964-65. Photograph by David McCabe.[/caption]

For much of his long life — he died in 2005 at age 98 — Johnson hid his gay identity from the public, though it was well known in his social circle. It seems ironic that someone intent on keeping his private life secret should build himself a transparent home, in which everything that happens in every space except the bathroom is fully visible to the outside world. Of course Johnson’s “glass closet” sits deep into his own property, far removed from the prying eyes of neighbors and passersby, so it feels less like a risk of exposure than a safe place in which to express his identity openly. And when privacy was required, the Brick House served as a sheltered retreat, as well as a guest cottage. Unfortunately it’s now under renovation, so visitors can’t see the interior, with its so-called cuddly bedroom, where Warhol slept under a canopy backed by a specially commissioned Ibram Lassaw wall sculpture.

Warhol’s multi-paneled 1972 portrait of Johnson, rendered in muted tones said to have been inspired by colors in the surrounding landscape, is on view in the Painting Gallery, together with works by Rauschenberg and Robert Indiana. A video in Da Monsta traces the personal and professional interactions of his circle, dating back to his student days at Harvard. Photographs, documents, and correspondence add to the feeling of intimacy, shared concerns, and mutual support among this group of gay men.

Another ironic twist to the Johnson story is that his homosexuality, kept hidden for so long, is now widely accepted, while his overt Nazi sympathies, which he later vehemently repudiated, remain repugnant. He should have kept those feelings locked in the closet.