As a boy, Jeffrey Sussman spent Saturday mornings working at his father’s garment manufacturing facility in Queens, one of two such shops his family owned.

“I would work from 9 to 1 every Saturday and did mundane things like sweeping the floor, cleaning up scraps of cloth, and carrying heavy bolts of fabric from the basement to the cutter’s table, where it would be unrolled and dress patterns placed over it,” Sussman explained.

Then, one day, the youngster witnessed a rather testy exchange taking place between his father and a man he did not know.

“I was coming up from the base ment with a load of fabric and I heard my father and another man screaming at each other at the top of the stairs. I noticed my father had clenched fists and was ready to hit this man,” Sussman recalled. “My dad told him to ‘Get the f--- out of here.’ The guy pointed his finger at my dad like a gun and said, ‘We’ll get you.’”

That incident was Sussman’s first introduction to the world of New York mobsters, and after the altercation, his father explained that the man, a notorious labor and teamster racketeer, wanted to unionize the shop’s employees.

“But the employees realized they’d make less than what my father was paying them,” said Sussman.

[caption id="attachment_103449" align="aligncenter" width="450"] East Hampton author Jeffrey Sussman.[/caption]

East Hampton author Jeffrey Sussman.[/caption]

Fortunately, Sussman’s mother had a cousin who had partnered with a group of mobsters during the depression and he had once even been bailed out of jail by Sussman’s father.

“He was very beholden to that,” explained Sussman. “So when my father had the problem with the gangster, my mother’s cousin negotiated a deal and though the shop was not unionized, my father still had to use the trucking company of the mob to deliver finished garments.”

As a native New Yorker, it’s perhaps no surprise that Sussman takes a keen interest in these colorful mob figures from the city’s bygone era. What is somewhat surprising, however, is the fact that in his youth, Sussman had more than one brush with members of their ranks. In addition to the episode at his father’s shop and the involvement of his mother’s cousin in the mob, Sussman’s great uncle was a bootlegger who was eventually indicted for the murder of Dutch Schultz, though he was never tried for the crime.

“I only met him once,” Sussman said. “He became very wealthy and had a mansion next to the governor’s mansion upstate.

“So through my own personal history, I realized I know a lot about the mob, so why not write a book about it?” he said.

Sussman has done exactly that, and on November 15, his newest book, “Big Apple Gangsters: The Rise and Decline of the Mob in New York,” (Rowman & Littlefield) was published. In the coming weeks, he will take part in virtual book discussions at local libraries.

Sussman has done exactly that, and on November 15, his newest book, “Big Apple Gangsters: The Rise and Decline of the Mob in New York,” (Rowman & Littlefield) was published. In the coming weeks, he will take part in virtual book discussions at local libraries.

While his 2019 book, “Boxing and the Mob: The Notorious History of the Sweet Science,” offered an inside look at how the sport was controlled by organized crime, in “Big Apple Gangsters,” Sussman, a part-time East Hampton resident, revisits the history of organized crime in New York City.

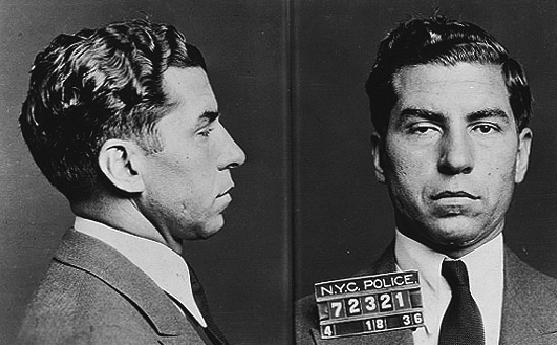

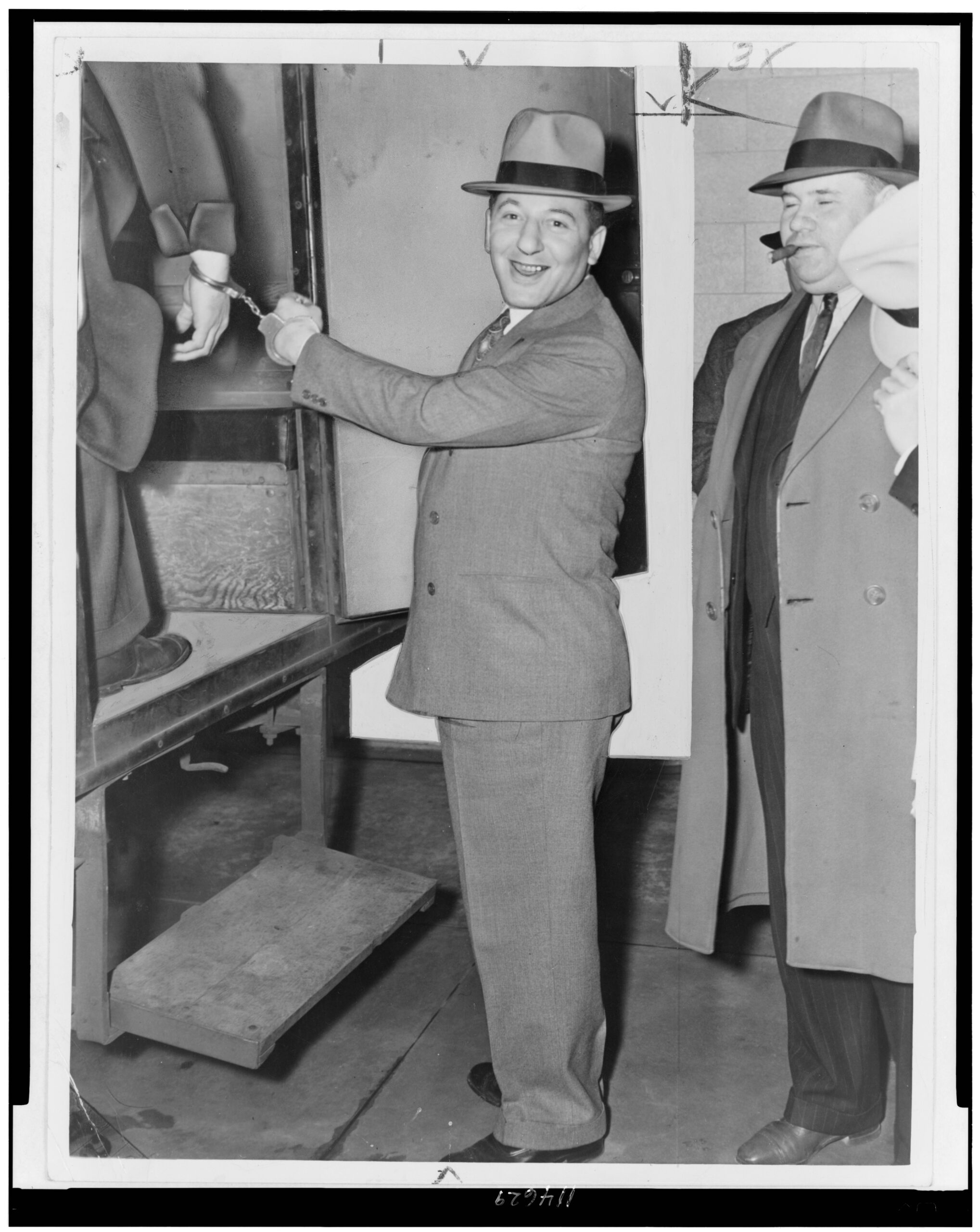

He begins with Arnold Rothstein (fixer of the 1919 World Series) and his four protégés: Meyer Lansky, Lucky Luciano, Bugsy Siegel and Frank Costello, who took out the two initial Mafia families run by Joe “The Boss” Masseria and Salvatore Maranzano. From the advent of bootlegging during prohibition, Sussman winds his way through the machinations of Luciano and Lansky’s National Crime Syndicate, which oversaw New York’s five Mafia families, and takes readers through the decades, revealing the wave of murders conducted by Murder Inc., the labor racketeering of Louis Lepke Buchalter (the only mob boss to die in the electric chair at Sing Sing), and ending with the conviction of the bosses of those five families and an examination of the mob’s continuing role in New York commerce.

Along the way, the book offers portraits of mob figures such as Carlo Gambino, Vincent “The Chin” Gigante, “Crazy” Joey Gallo, John Gotti, Sammy “The Bull” Gravano, and Greg Scarpa, who became an FBI informant and was instrumental in extracting confessions from the killers of three civil rights workers in Mississippi in 1964.

Sussman notes that through his research, which included talking to a lot of people who gave him lots of tidbits of information that hadn’t been reported before, he was able to debunk some of the myths about the mob. One of the most prevalent of those myths is that the Jewish and Italian mobsters were at odds with one another.

“That is incorrect,” said Sussman. “Frank Costello took an Irish name because he was dealing with Irish bookmakers and bootleggers and he was married to a Jewish woman. There was also a media myth that you can’t join a crew unless you were Sicilian on both sides. But John Gotti’s wife was Jewish and their son was a made man.”

The multi-ethnic nature of the mob is something that ultimately helped the groups succeed, and Sussman notes that, despite their ancestral or religious differences, 20th century mobsters all shared a common background in that they were the children of recent immigrants to the United States. He adds that in the late 19th and early 20th century, multi-ethnic New York gangs were the pre-cursers of organized crime and members would typically work for politicians and fight each other.

[caption id="attachment_103451" align="aligncenter" width="557"] A 1936 mug shot of Charles "Lucky" Luciano.[/caption]

A 1936 mug shot of Charles "Lucky" Luciano.[/caption]

That all changed with Arnold Rothstein.

“When Arnold Rothstein came to power and was teaching his four proteges about organized crime, he said, ‘We don’t have to fight each other. We can run this like a business with price fixing and we’ll have corporate meetings,’” said Sussman. “He said, ‘In addition, the politicians will work for us. In the future, we’ll be able to buy and sell the politicians.’”

As a result, the first generation mob members all cooperated with one another, but as the years went by, priorities and goals shifted among ethnic groups.

“The major difference between the Jewish and Italian mob is that the Jewish gangsters didn’t want their sons to become gangsters and instead wanted them to become doctors or lawyers,” said Sussman. “The Italians wanted their sons to continue in the family and build a dynasty. So by the beginning of the ’90s, there were very few Jewish gangsters left.

“I think they grew apart and had less in common,” he added. “However, many of the casinos in Vegas are still owned by Jewish and Italian mobs.”

Ironically, it was Rudolph Giuliani who, as U.S. Attorney in New York in the mid-1980s, was able to get indictments and convictions for the heads of the so-called “Five Families” — the Genovese, Gambino, Lucchese, Colombo and Bonanno crime families — who for decades controlled New York and the surrounding areas.

[caption id="attachment_103452" align="aligncenter" width="477"] Lepke Buchalter, head of Murder, Inc., was executed by electric chair at Sing Sing in 1944. Library of Congress photo.[/caption]

Lepke Buchalter, head of Murder, Inc., was executed by electric chair at Sing Sing in 1944. Library of Congress photo.[/caption]

“They all got long prison sentences. What mob attorneys are now doing is advising them to avoid being ensnared under the RICO [Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations] statute that can result in lifetime in prison,” said Sussman. “Before, they might have served five to 10 years, which they were willing to pay, but no one want to go to jail for 100 years.”

But that doesn’t mean organized crime is a thing of the past. Sussman said that Russian and Chinese immigrants are now forming gangs, which is typical for immigrant groups. These days, he explained, the mob and its members rely on shell companies in order to distance themselves from criminal activity, making it difficult to trace.

“They are now heavily involved in real estate. Lots of buildings are owned by mobsters,” said Sussman. “After the main mobsters made so much money, they invested in legit and semi-legit businesses. They own some large trucking companies, they have investments in resorts and have incredible money in politicians.

“They’re still shaking us down — but at a different level.”

Jeffrey Sussman discusses “Big Apple Gangsters: The Rise and Decline of the Mob in New York” in a series of virtual presentations. Register by visiting the websites: Friday Night Dialogues at Shelter Island Public Library, Friday, November 20, 7 p.m., shelterislandpubliclibrary.org; Rogers Memorial Library, Wednesday, December 2, noon, myrml.org; Westhampton Free Library, Saturday, December 5, 2 p.m., westhamptonlibrary.net.