In August, the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill opens “James Brooks: A Painting Is a Real Thing,” the first full-scale retrospective of the pioneering Abstract Expressionist artist in 35 years. The show runs August 6 to October 15 and it features over 100 key paintings, prints and works on paper spanning more than a half century.

Books (1906–1992) was a celebrated painter of the 1950s New York School who embraced experimentation and risk throughout his seven-decade career. This exhibition includes works by the artist from the 1920s to 1983, primarily selected from a major gift to the museum by the James and Charlotte Brooks Foundation in 2017, as well as loans from public and private collections.

“A Painting Is a Real Thing” is organized by Klaus Ottmann, Ph.D., the newly appointed adjunct curator of the collection, with support from assistant curator and publications coordinator Kaitlin Halloran. The exhibition will be accompanied by a fully illustrated, 176-page catalogue with interpretive essays by Dr. Ottmann and contributing essayist and artist Mike Solomon, a detailed chronology, a complete plates section, and an exhibition checklist.

“James Brooks was not only a principal creative force in defining and expanding the Abstract Expressionist canon, but an early acolyte of a Southwestern abstract regionalism that emerged out of Dallas, Texas, in the 1920s,” said Dr. Ottmann. “He was one of the most accomplished muralists of the WPA era, and one of a small group of “combat artists” during World War II — all of which is represented in this exhibition for the first time thanks to the significant gift of works to the Parrish by the James and Charlotte Brooks Foundation.”

Organized chronologically, “A Painting Is a Real Thing” begins in the 1920s with work by Brooks shaped by Social Realism and further developed in New York where he worked as a sign letterer and WPA muralist and studied at the Art Students League (1927–1930), followed by abstract works from the 1930s. The exhibition picks up after Brooks returned from service in WWII as a combat artist, with works that reference the military, and through his period of experimentation with abstraction that led to a career-defining development in 1948. As he worked on an oil on paper series that involved gluing paper to canvas, the paste bled through, essentially creating another painting on the reverse side. The unexpected consequence was the genesis of a new direction the artist would pursue for decades: a staining technique that inspired a more improvisational approach, as in “Maine Caper” (1948), in which swaths of shape and color overlap in a free form composition.

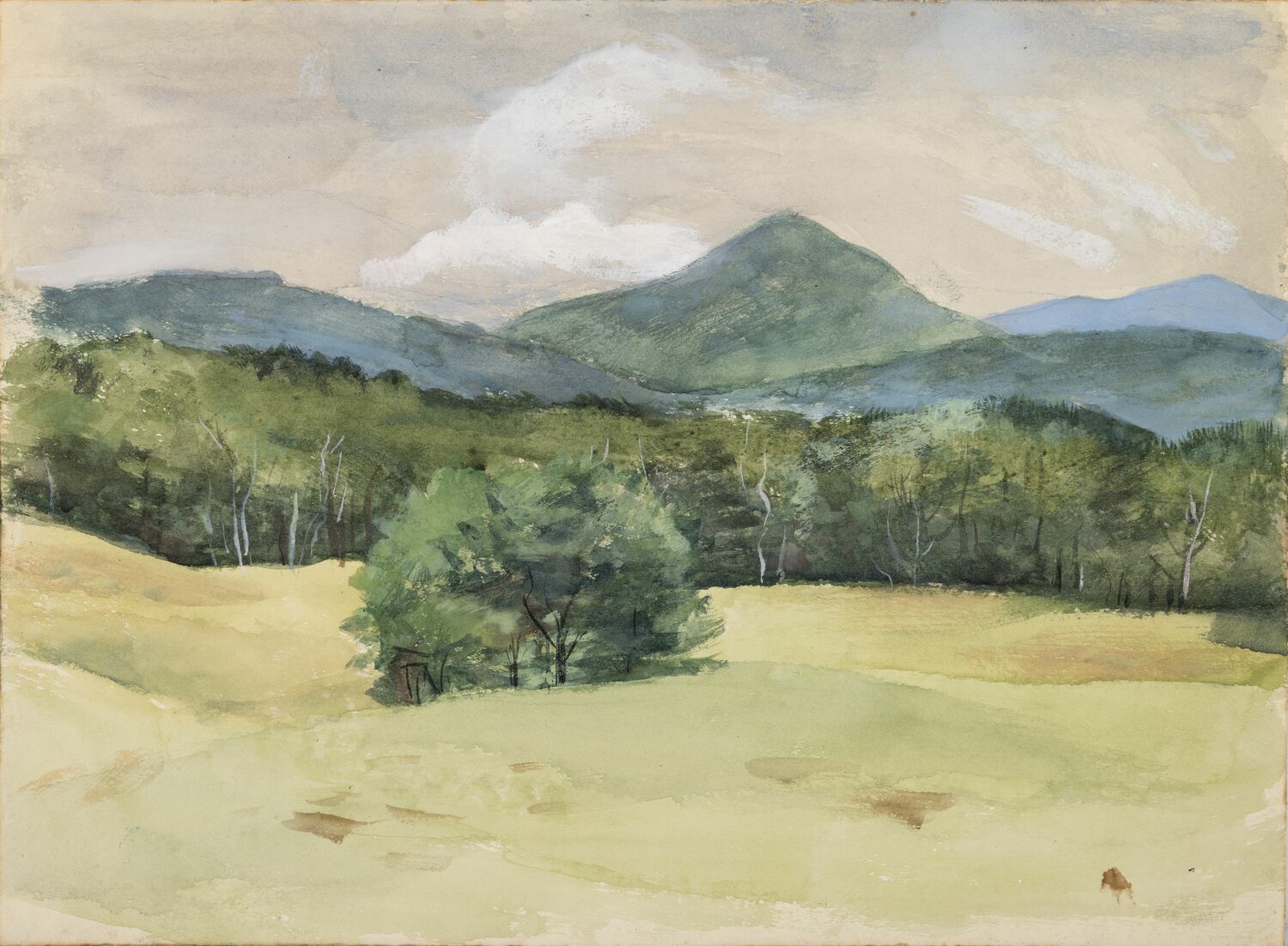

In 1949, at the urging of Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner, Brooks and his wife, Charlotte Park (American, 1918-2010), began to visit the East End and rented a house in Montauk. By 1957, Springs became their permanent residence. Exploring scale and an expanded use of materials, Brooks pushed the limits of the stain technique, working both sides of a painting. Unprimed Osnaburg cloth allowed paint to seep through the surface in a conflation of chance with choice, resulting in spontaneous forms as in “G” (1951). Crayon gave definition to paint in “Untitled” (ca. 1950), and sand was a significant element in “Dolamen” (1958). Brooks dramatically increased the scale of his work with “Obsol” (1964) — an 80- by 74-inch oil painting. To emphasize the abstract nature of his work, the artist titled paintings with his own invented words, devoid of connotation, context or reference to representation.

Two additional developments arose in the 1960s: a shift from oils to acrylics, prompting the use of a wider range of color, and a move toward simpler compositions. In “Juke” (1962-70), a more expansive gestural sweep replaces the density of previous work. Brooks reached a new level of simplicity in “Ypsila” (1964), a monochromatic painting where wispy, free-form black lines blow across the white canvas.

By 1969, Brooks moved into a purpose-built studio of his own design where a larger space and expanse of skylights led to an increase of scale and productivity. A selection of acrylic paintings and lithographs dating from 1970 and onward reveal the artist’s commitment to color as a consistent and essential ingredient in his pictures, where plain white canvas was often replaced with colored ground. Later large-scale paintings like “Yarboro” (1972), with its biomorphic shapes and restrained palette, and “Cambria” (1983), where that concept is further developed, reveal how Brooks continued to seek new territory each time he approached the canvas.

The Parrish Art Museum is at 279 Montauk Highway in Water Mill. For more information on the show, visit parrishart.org.