One-hundred and fifty six. That’s the number of victims who spoke over seven days at the sentencing hearing of Dr. Larry Nassar in Lansing, Michigan, in January 2018.

For years, Nassar was USA Gymnastics’ (USAG) national team doctor, as well as a physician at Michigan State University (MSU). A pillar of his community, he also worked with dancers and athletes at a high school near where he lived. Over three decades, it’s estimated that he sexually abused hundreds of female athletes under the guise of “medical treatment.” Among the many USAG national team members who say Nassar sexually assaulted them are top gymnasts Aly Raisman, Gabby Douglas, Jordyn Wieber and Simone Biles.

In November 2017, Nassar pleaded guilty to seven counts of sexual assault of minors, thereby avoiding a trial. But during his sentencing hearing Judge Rosemarie Aquilina allowed any of Nassar’s victims, not just the seven, the opportunity to speak if they wanted. The 156 who addressed him in court represented a cross-section of the estimated hundreds of girls, many of them now grown with children of their own, who were sexually abused at the hands of the doctor over the years.

“I just signed your death warrant,” Judge Aquilina famously said in the courtroom as she imposed a state prison sentence of 175 years on Nassar. In July 2017, Nassar had been sentenced to 60 years in federal prison on child pornography convictions. In February 2019, he received an additional 40 to 125 years in state prison after pleading guilty to three more counts of sexual assault.

The sentences will be served back to back, ensuring that Nassar, 56, will never leave prison.

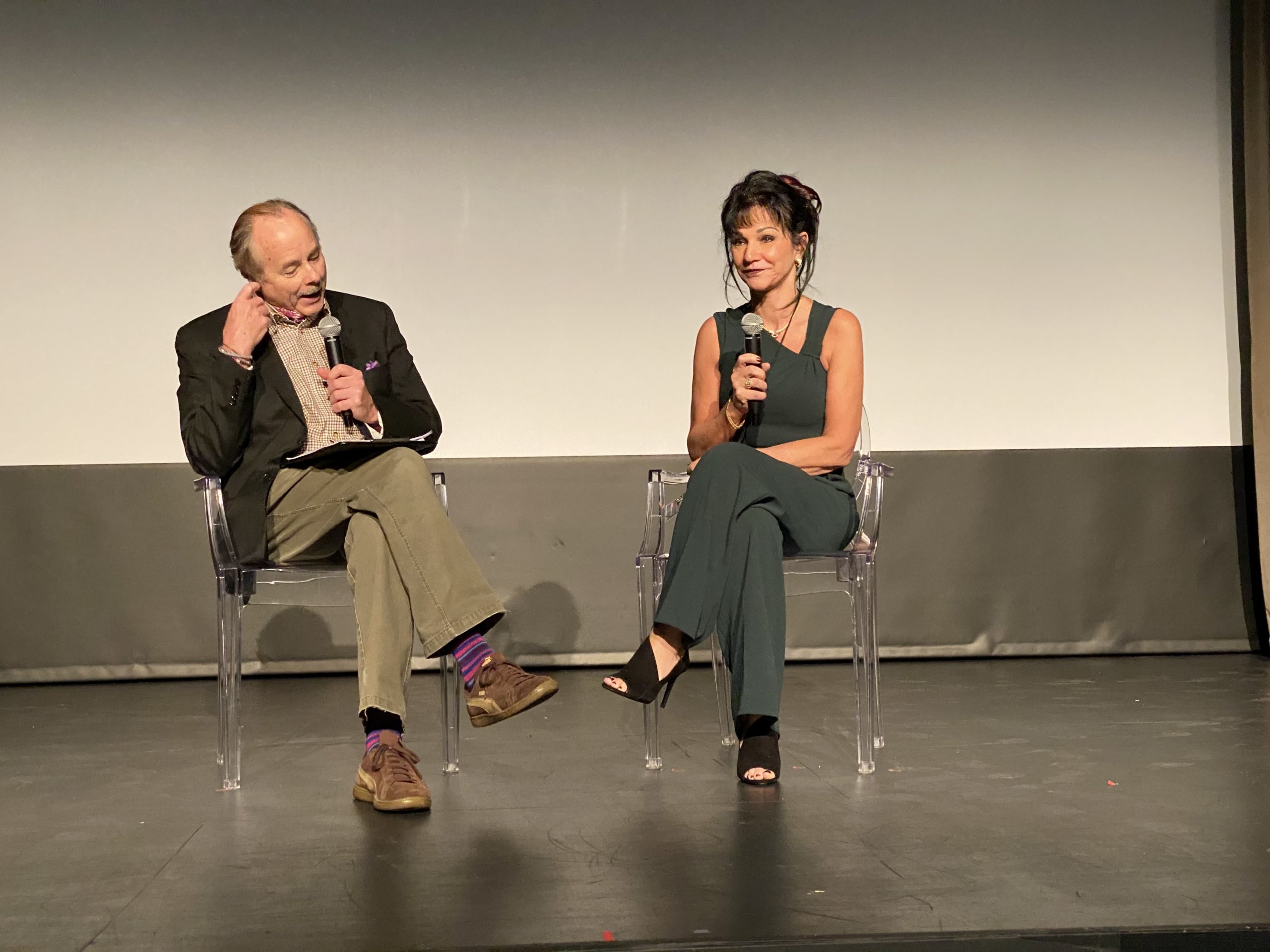

On December 6, the HBO film “At the Heart of Gold: Inside the USA Gymnastics Scandal” was screened at Southampton Arts Center as part of the Hamptons Doc Fest. In attendance was Judge Aquilina who spoke with host Andrew Botsford in a Q&A following the screening. The film was directed by Erin Lee Carr and it featured interviews with many of Nassar’s victims who shared their stories on camera after years of silence. It was a silence that had been broken in 2016 when one of his victims —Rachael Denhollander — went public with her story in the Indianapolis Star. The story made national news, starting the flood of women who came forward to file lawsuits against Nassar and the institutions that had long protected him.

“What you didn’t see in the film is that cameramen who have seen everything, including crimes and death, not one of them had a dry eye in seven days,” said Judge Aquilina of those who witnessed the victims’ statements in court. “Those 156 I dubbed ‘sister survivors.’”

The case shocked the nation, but perhaps even more astounding than the number of victims who spoke at Nassar’s hearing was the number of years it took to bring him to justice in the first place. The film makes the case that gymnastics, as a sport, works in a predator’s favor. Competition is fierce and girls are trained to be tough. They work through pain and suffer in silence — lest another girl waiting in the wings swoops in to take their place. It’s also a sport in which coaches, trainers and medical staff must frequently touch athletes’ bodies as they correct form, work on sore muscles or evaluate injuries – again, all things that can work in a predator’s favor.

It’s also apparent that in Nassar’s case, the system, whether intentional or not, protected an abuser who was hiding in plain sight, and it worked against the few girls who were brave enough to speak out. The adults in charge were complicit as they disavowed victims’ claims and swept allegations under the rug in a culture of indifference that protected a serial predator for years.

While Judge Aquilina notes that some of her fellow judges were critical of the idea of allowing so many victims to speak at the hearing, she adds that no victim can show where the pain ended, either for them or their family members.

“Crime has a huge ripple effect and defendants need to hear how deeply and how expansive the pain went and the damage they caused,” said Judge Aquilina. “I also let the defendant speak.”

“Sometimes they didn’t know they hurt someone so deeply – if you’ve done this and if we’ve treated them right and let them come out of the prison, they can do better,” added Judge Aquilina of defendants. “Our gavels should be used as healing ones when we can. I have people bring me artwork, healthy babies, tell me I just got an AA coin for 10 years sober, and they say thanks to you, you’re the first to tell me I matter and believe in me and hear me. I would hope every judge would do that. “

But Judge Aquilina adds that Nassar’s words and actions in court did nothing to improve his standing with her. Even as he attempted to be contrite toward his victims, Judge Aquilina felt Nassar was trying to manipulate them by turning his head, looking back to catch the eyes of those he had harmed, until the judge admonished him and sternly told him to face her when he spoke, not them.

In a letter he had written to the court, Nassar referenced his victims by saying “Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned.” There were gasps in the courtroom when Judge Aquilina read that portion of the letter, which she felt illustrated that Nassar harbored little remorse for his crimes or a desire to change.

“He’s a true predator,” said Judge Aquilina. “All predators want control, and you see that throughout the film. That’s why this is important, it’s about grooming predatory behavior and what we can do to change a broken system.”

To that end, Judge Aquilina noted that it’s important to change perceptions of what a predator looks like. Sometimes, the predator is the cheerful family friend or the helpful doctor.

“We have to give children the ability to say, ‘No, I don’t want to go to the man’s house,’” she said. “Thirty years ago, if one person had listened I would have never heard this case. If we don’t change this it will continue … it’s an epidemic.”

In the end, the heroes of the story are the many victims who found strength by speaking up to tell the truth, allowing them to begin healing a wound that in many cases, was decades old.

“The benefits were for the victims. It was a magnificent accomplishment,” Judge Aquilina said. “Those very strong women, they were babies, six years and older, when it happened, and it took so much courage for them.”

“They didn’t just leave pain, they took power back and empowered each other. They came in shy and forlorn and they grew 10 feet and had a light around them and I felt them heal,” she said of their statements. “They empowered me to go to the next one.”

So far, Judge Aquilina says a total of 505 girls who were abused by Nassar have come forward, but hundreds of others haven’t. For the 156 who appeared in her courtroom, speaking out was a major victory for them all.

“They said ‘I’m not a number, I’m a name. You hurt me and I’m taking my power back,’” she added. “I’ll never have so many pillars of strength come before me.”

“At the Heart of Gold: Inside the USA Gymnastics Scandal” was produced by Dr. Steven Ungerleider and David Ulich of Sidewinder Films, the production arm of The Foundation for Global Sports Development. The foundation is dedicated to fighting sexual abuse and has committed $1 million towards a new education program called COURAGE FIRST, an abuse prevention program that collaborates with survivors and leading national child abuse prevention organizations. The program educates adults, through online learning tools with podcast, blogs and videos, on the prevalence and warning signs of sexual abuse and empowers them through certification through a partnership with Darkness to Light. Visit globalsportsdevelopment.org to learn more.