In 1965, the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London presented Lee Krasner’s first retrospective exhibition. It was also her first overseas exposure, and it proved to be her last solo show abroad — until now, 35 years after her death. In a triumphant return to London, “Lee Krasner: Living Colour,” at the Barbican Art Gallery through September 1 and traveling to three other venues in Europe, places her in the context of international modernism, where she always insisted her work should be judged.

While it’s not a true retrospective, since a few key phases are missing — including her cubist paintings from the late 1930s, when she was at the forefront of the young American abstractionists — the show hits many of the pivotal points in Krasner’s 50-year career, from her early self-portraits to the 1970s collages that illustrate her longtime practice of recycling earlier work. In fact, due to her periodic revisions, her oeuvre comprises only about 600 pieces, of which 74 are on view.

With its mezzanine divided into relatively small bays, the Barbican is not the most sympathetic exhibition space, but the show’s curator, Eleanor Nairne, has used the divisions to advantage. She was helped by Krasner’s self-described “breaks,” abrupt changes of artistic direction instead of smooth transitions. And often, when Krasner became dissatisfied with what she was doing, she transformed it out of all recognition. For example, most of the canvases from her 1951 exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery in New York City — her first solo show — became the backgrounds for large-scale collages a few years later. The overlays of cut and torn paper and fabric vitalize what were rather static compositions. Two outstanding examples, “Milkweed” and “Blue Level,” are included in the current show, as are several more of the 1953-55 collages that announced Krasner’s emergence as a force to be reckoned with in the New York avant-garde.

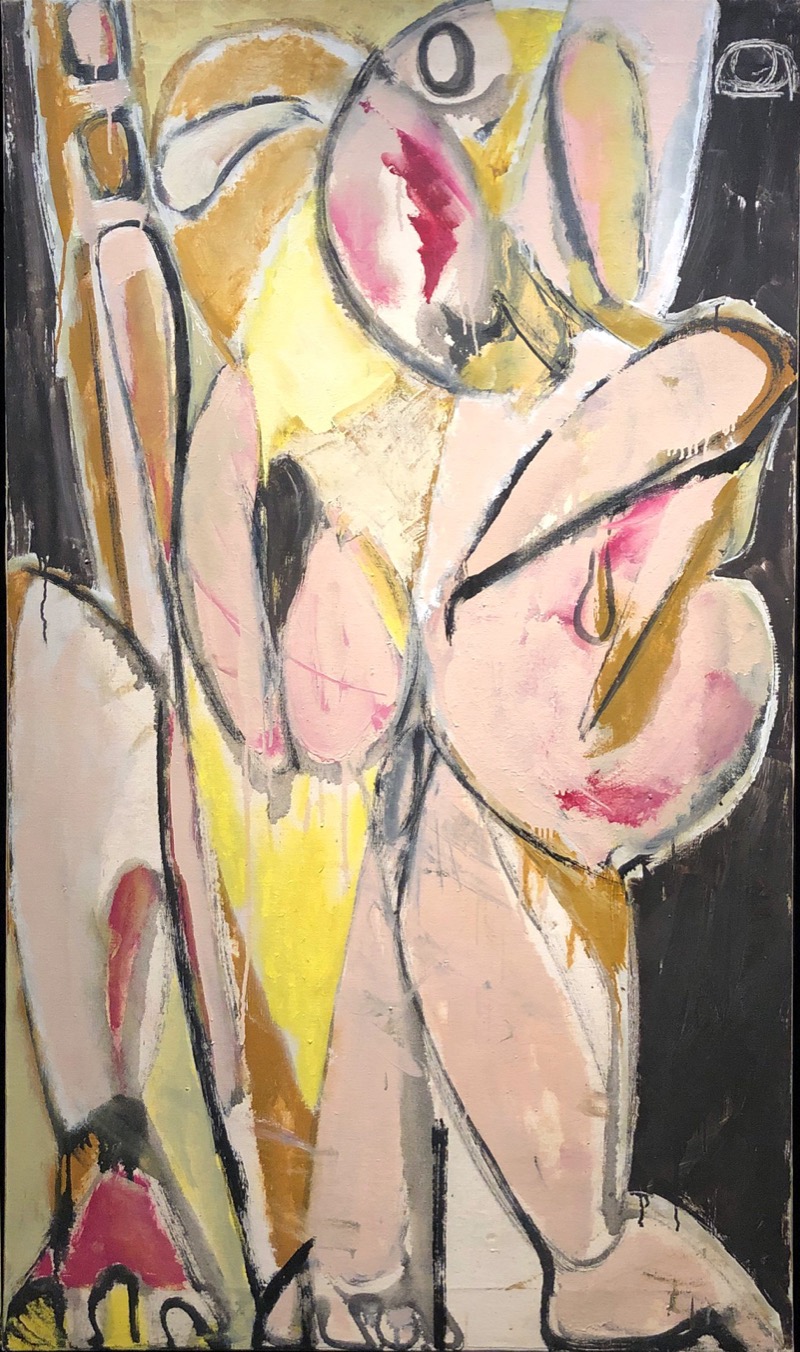

No sooner had she scored this success than she abandoned the collages to embark on a series of nature-based abstractions. Bordering on the grotesque, the forms are swollen with pent-up energy, reflecting the turmoil of her personal situation. In the spring of 1956, her marriage to Jackson Pollock in crisis due to his infidelity, she painted a bloated figure with a gash in its face, overlooked by an evil eye scratched into the black background. That canvas, later titled “Prophecy,” was on her easel in July when she traveled to Europe, while Pollock stayed behind. During her absence, he was killed in a car crash, leaving her to deal with the aftermath and to confront the image that foretold his death. Remarkably, this tragedy did not derail Krasner’s creative drive. Three related works painted soon after her return occupy a decisive position in her development, signaling her determination to persist. The bay that contains these four canvases is one of the show’s highlights.

What followed in 1957 was a group of life-affirming paintings, full of sweeping gestures and vibrant colors, known as the Earth Green series. She had moved out of her small studio in the house and taken over Pollock’s barn studio, where she was able to expand her scope, mounting her canvases on the walls and surrounding herself with works in progress. Sadly, none of the Earth Green paintings are in the exhibition, making the shift, two years later, to her nearly monochrome Umber series seem all the more abrupt. Five of those paintings, including the monumental “The Eye is the First Circle,” 1960, occupy the Barbican’s lower gallery, which has ample wall space to accommodate large works. Masterpieces from the following decade, such as “Another Storm,” “Combat,” “Siren” and “Icarus,” demonstrate her increasingly ambitious exploration of spontaneous action painting, and a group of beautiful works on paper shows that, even in a small format, she could create powerful imagery.

In the 1970s another break occurred, resulting in crisper, more geometric compositions. Two of those canvases are included, foreshadowing Krasner’s major collage series of 1976-77, titled after conjugations of the verb, “To See.” Composed of cut-up drawings from her time at the Hans Hofmann School of Art in the late 1930s, they proclaim her need to re-invent herself as often, and as ruthlessly, as necessary. The show ends there — on a high note, to be sure, but omitting the last five years of her productive life, when she continued to reconsider earlier work to find the way forward. As she asserted, “The past is part of the present, which becomes part of the future.”