As a high school student at St. Margaret’s Academy in Minneapolis, Catherine Creedon recalls being deeply moved by “To Believe in God,” a 1968 book filled with thoughtful, poetic insights into the nature of spirituality accompanied by colorful and engaging illustrations. The title, which was recently rereleased by Echo Point Books, was the first of three in a collaborative set titled “To Believe” (“To Believe in Man” came in 1970, followed by “To Believe in Things” in 1971) by author, poet and ordained priest Joe Pintauro, and artist, illustrator and designer Sister Corita Kent.

“It’s an amazingly beautiful book. I actually stole the book from the library,” confessed Creedon, who is now, ironically, the director of the John Jermain Memorial Library in Sag Harbor. “I think I had to return it to graduate.”

Also ironic is the fact that after leaving the priesthood in 1966, Pintauro, who went on to have a storied career as a novelist, playwright and photographer, settled in Sag Harbor and eventually became good friends with Creedon and her husband, Scott Sandell.

“But for me, my relationship with Joe predates my friendship with him,” Creedon said with a smile during a recent interview at the library. “That book was a huge moment for me, of personally seeing my own life through the lens of history. As a 17-year-old girl in the Midwest, I never thought I’d be having dinner with Joe Pintauro.”

Which is one of many reasons why it is so fitting that upon his death on May 29, 2018, at the age of 87, Pintauro bequeathed his literary archives to the John Jermain Memorial Library. Now, after several postponements in the last year due to COVID-19, on Friday, June 11, at 6:30 p.m., the Joe Pintauro Papers will finally and officially be dedicated at the library with an in-person event for a limited number of people.

“The Pintauro collection is the most stunning we’ve gotten in recent years,” said Creedon. “Joe said, ‘I need someone who will hold these collections in trust for the future.’ That was really exciting. Joe was a really good friend of mine and a better friend of my husband. I’ve known of the potential for this gift for awhile, but when it comes to you, that when it’s finally real.”

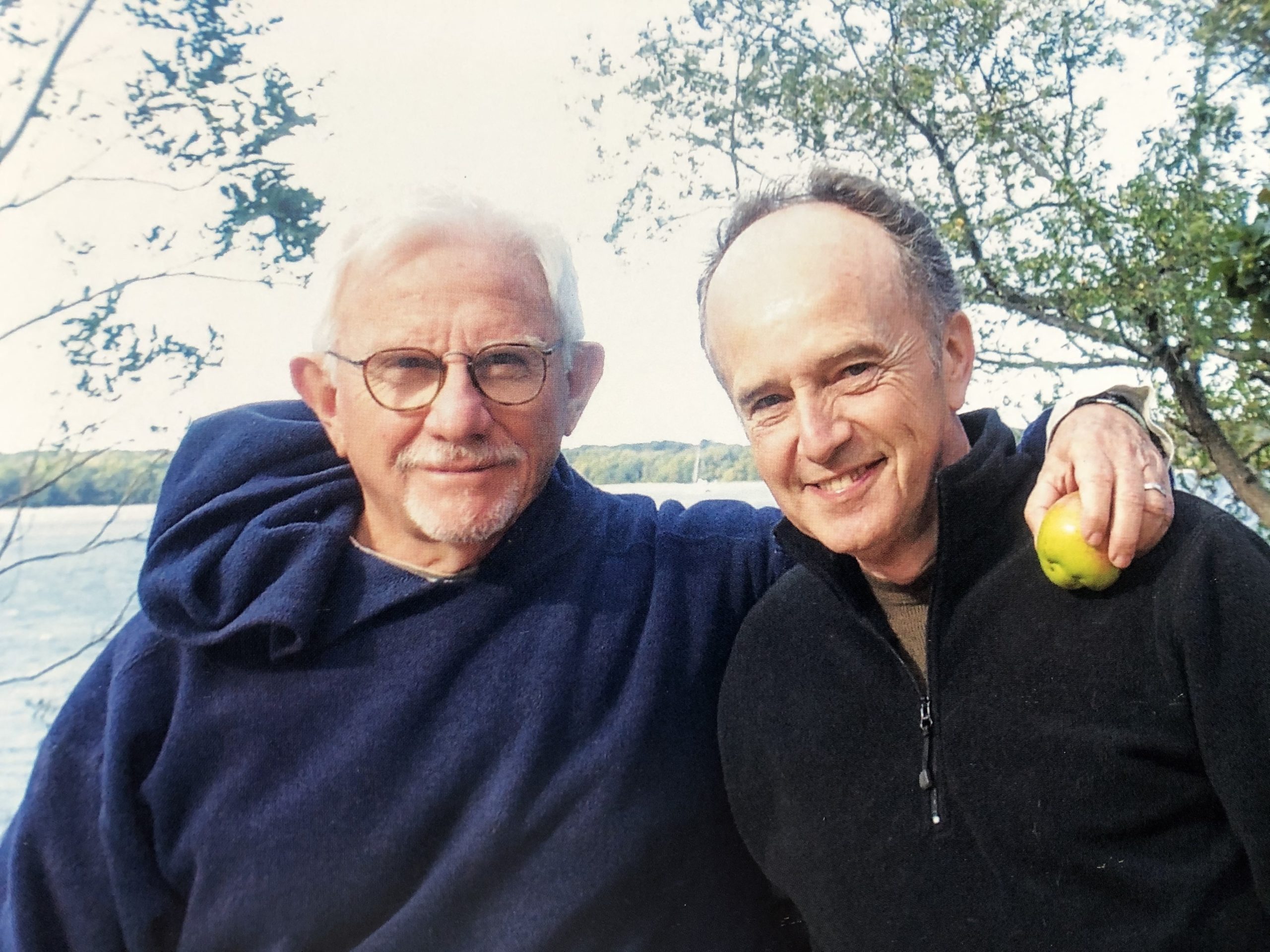

Managing the collection is archivist Rebecca Grabie, who joined the staff of the John Jermain Library shortly after Pintauro’s death. In the months that followed, she worked closely with Greg Therriault, Pintauro’s longtime partner and husband since 2013, to organize and catalog the material and put it into context.

“I had lots of meetings and discussions with Greg,” said Grabie. “The archival material is Joe’s personal scripts. They often have annotations from friends that he had feedback on. There’s also a lot of the documentation of the performances of his plays, you can see when they were performed — West Coast, East Coast, internationally.

“He did so much,” she added. “He was a poet, novelist, playwright, nonfiction writer — there’s a lot in there from each area. We have correspondence too — one letter from Irwin Shaw and one from Studs Terkel, both congratulating him on his novel. Joe was friends with Nelson Algren, who lived in Sag Harbor and Studs was a friend of Nelson’s in Chicago.”

Therriault left Sag Harbor after Pintauro’s death, relocating to his native upstate New York in order to be near his family. He now lives in Niskayuna, a small town near Schenectady, but will be returning to Sag Harbor in order to take part in a discussion with Grabie at the June 11 dedication, where he will offer insight into the importance of his late husband’s work.

“I moved to Sag Harbor at the age of 29 and met Joe in 1978,” Therriault said in a phone interview from his home. “As I prepared the archives, I was ever more aware of the depth and breadth of Joe’s knowledge and of his capacity to express and articulate with empathy, compassion and forgiveness the full range of human experience.

“Whether in his poetry, plays, novels or his photographs, Joe’s belief in the power of nature and the capacity of the human spirit is always present,” he added. “Forty years is a great amount of time to be in someone’s presence, and Joe’s still with me — in our books and our cats.”

After publication of his “To Believe” books and “The Rainbow Box,” a series of four books, one for each season, created in collaboration with artist Norman Laliberte in 1970, Pintauro published his first novel, “Cold Hands,” in 1979. His many plays followed, the first of which “Snow Orchid,” was staged by Circle Repertory Company in 1982. Others included “The Dead Boy” in 1990, about a young man’s sexual abuse allegations against a Catholic priest, and “Raft of the Medusa,” a 1991 play that takes place 10 years after the AIDS crisis and centers on a weekly support group for those living with HIV and AIDS.

Pintauro also worked closely with Bay Street Theater founders Sybil Christopher, Emma Walton Hamilton and her husband, Stephen Hamilton, to pen “Men’s Lives,” a stage adaptation of Peter Matthiessen’s 1986 non-fiction book about the baymen of the East End. The play had its world premiere at Bay Street and was the theater’s inaugural production in 1992 when it first opened its doors. In 1995, Pintauro collaborated with fellow playwrights Lanford Wilson and Terrence McNally, who lived in Sag Harbor and Water Mill, respectively, on another play that had its world premiere at Bay Street Theater: “By the Sea, By the Sea, by the Beautiful Sea.”

These two plays, perhaps, represent one of the most significant aspects of Pintauro’s time in Sag Harbor — the creative collaborations which he engaged in throughout his life and career, particularly here on the East End.

“One of my favorite pieces in the collection is a paperback of ‘Men’s Lives,’ because it has highlights and sticky notes from after conversations he had with Emma and Steve,” said Grabie. “They were their notes about how they might be able to adapt the play.”

“There’s so much that is collaborative in Joe’s work. The drafts of ‘Men’s Lives’ speaks of his collaboration with Emma and Sybil and Steve and is one of the most important things highlighting his career,” adding Therriault, noting that it was just one of many collaborations he engaged in with fellow theater artists, especially at Circle Repertory Company in Manhattan.

“There’s a rich trove of photos and letters and scripts of plays that were workshopped there. When Lanford and Joe were company playwrights, they’d host playwrighting workshop weekends in Sag Harbor and move between Lanford’s house on Suffolk Street and our house on John Street,” recalled Therriault. “They’d stay with us or Lanford and read new plays, make great food and have a wonderful artistic, creative kind of weekend.

“This was happening in the early ’80s. It was a very special time and there’s a lot of material that has to do with that time as well.”

In any collaboration, there must be a sense of trust, and Therriault notes that with his final gift to the John Jermain Memorial Library, Pintauro placed his legacy in the hands of those who will now be the guardians of his archive for future generations.

“Joe trusted Cathy and her staff to be the recipient of the archives and he believed in them. They’re proving to me how worthy of Joe’s trust they are in honoring him in such a wonderful way. He would be pleased,” said Therriault. “The thing about Sag Harbor, Joe really felt at home there. He felt the goodness of the people there. I think he was the first to give a commencement address at Pierson from the arts community. He spoke about the value of home and a place like Sag Harbor, encouraging graduates to leave and strike out, but reminding them that this is home and you can always come back here.”

Being a repository of the documents and stories that have come before is an important aspect of any library, and with Sag Harbor changing at an ever faster pace, for Creedon, safeguarding the archives of artists and writers like Pintauro serves a higher purpose, one that will not just serve those living in the village today.

“I think that’s an essential part of a good public library mission, particularly one like JJML,” said Creedon. “In many ways, we are the physical face of the history of Sag Harbor, the philanthropy of Mrs. Russell Sage, who built the library, the development of this community from whaling to factory town. It holds that the next wave of Sag Harbor history, the artists and writers, and the library addition itself, is a reflection of the community.

“It holds in trust our history of expansion and a series of movements,” she added. “Joe embodied two of those movements — coming with the artists and writers, hosting salons, then later in recognition through his collaborations that Sag Harbor was really something of a player in this culture. “

Now, Joe Pintauro’s archives will become a permanent part of the history of Sag Harbor, and going forward, will serve as a testament to the vision of a creative community in its place and time, long after all its players have left this earth.

“For me, the meaningfulness of that collection, in and of itself, traces that trajectory in the changes of the library. For someone who was friends with Joe, it’s a recognition that just as Joe has become part of history, I’ll, to a lesser extent, be a part of the history, too,” said Creedon. “The library restoration is done, but what it supports goes on forever. Joe will support the next generation. This community is changing really fast, but the library holds this past in trust.”

For more information about the dedication of the Joe Pintauro Papers on Friday, June 11, at 6:30 p.m., at the John Jermain Memorial Library, 201 Main Street, Sag Harbor, visit johnjermain.org. In conjunction with the dedication, Pintauro’s photographic work is also on view in an exhibition this summer at the library.