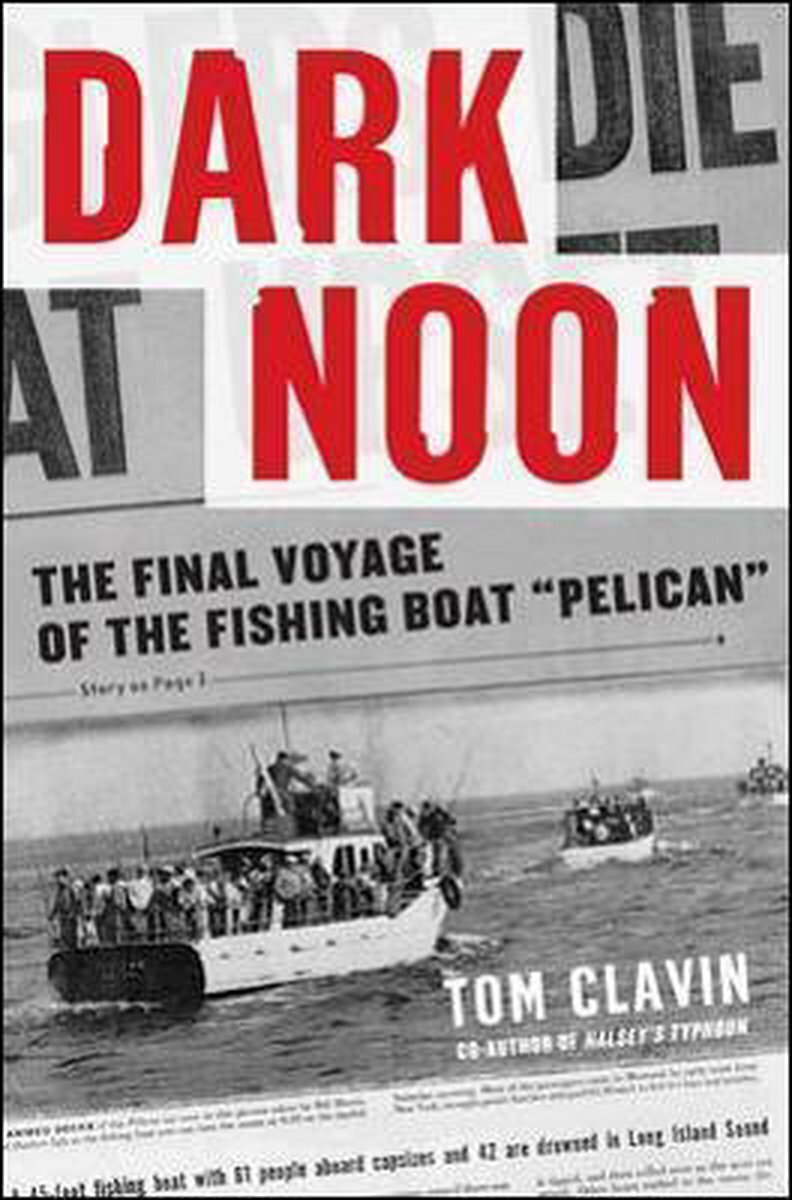

For a few hardy souls who remember, next week will mark the 70th anniversary of the capsizing of the Montauk fishing boat Pelican. For me, it’s a 20th anniversary because it was 20 years ago that I first learned of the terrible event that cost the lives of 45 people and began to develop a deep connection to it, which led to the writing of a book titled “Dark Noon.”

Sometimes you see a story and think it’s a good story. Less often, you see a story and think it’s a good story and you get to do something about it. In its edition of September 1, 2001, Newsday published a piece to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Pelican tragedy. It was an interview with Irene Stein, whose husband had perished that day, leaving her a widow with two young children. I clipped the piece out and stuck it in a pile … and the terrorist events 10 days later pushed it and a lot of other stories into the background. But I couldn’t stop thinking about Stein’s heartbreaking recollections, and about a year later, during a pile-reducing purge, the clipping surfaced.

For those of you not familiar with the event, here is what happened: On September 1, 1951, the 42-foot Pelican, captained by Eddie Carroll, left the dock at Fishangri-la on Montauk’s Fort Pond Bay with 64 people aboard. The Pelican was a “head boat,” meaning the more heads a skipper could count on his boat, the more money he made. That explains why the Pelican was so overloaded, as well as Carroll being an especially engaging and popular captain with whom anglers wanted to sail. The Pelican had the reputation of being a lucky boat.

On that sunny, mild Saturday morning, no one knew a violent and swift-moving storm was on its way. The boats left Fort Pond Bay and fanned out to favorite fishing spots. (The charter boats, or “six-packs,” went out of Lake Montauk.) Eddie’s was the Frisbie Bank south and west of Montauk Point. The Pelican proved lucky again as the anglers reeled fish in. The downside was as the storm approached, dark clouds blotting out the sun, the passengers prevailed upon Eddie to stay a little longer. By the time Eddie insisted they head home, it was already too late.

It got worse — the port engine would not start. Gamely, with just the starboard engine, the overloaded Pelican pushed into the escalating wind. When the storm hit, the waves leaped to 6 feet, then higher. Within sight of the Montauk Light the Pelican was caught in the Rip. Then an especially powerful wave struck the starboard side and the boat turned turtle. Except for 10 people trapped in the cabin, everyone was tossed into the turbulent sea. Many passengers could not swim and drowned clinging desperately to each other. Until his strength gave out, the doomed Captain Carroll helped people hold on to the overturned hull. Quite possibly, no one would survive.

But 19 did. A dozen were rescued by Lester Behan and his first mate, Bill Blindenhofer, aboard the Bingo II, after they witnessed the Pelican capsizing. Six others were hauled aboard the Betty Anne, a sailboat that was late seeking shelter. The Coast Guard found the 19th survivor hugging the boat’s hull.

Frank Mundus and Carl Forsberg had gone back out into the storm, and while there was no one else in the water when they arrived at the scene, they were able to use their boats to tow the Pelican back in. At the dock, a State Police diver extricated the 10 bodies from the cabin. For all the bodies recovered, a makeshift morgue was created at an icehouse owned by the Duryea family.

The bare bones of the story were riveting, but what could help the story go beyond tragedy? One was the Pelican event led to laws being enacted nationally that better protected boat passengers and led to many lives not being lost. Another was the way the Montauk community rallied to help the survivors and console the bereaved families. I became fascinated by the backgrounds of the 64 people from all over the New York metropolitan area who happened to be together on the Pelican that Saturday. And when word got around that I was working on a such a project, people reached out to help — sharing personal memories of the day or materials such as scrapbooks of clippings. Spurred on, I became a regular visitor to the basement of the Montauk Library, where Robin Strong presided over the local history collection.

“Dark Noon” was published in 2005 and I probably haven’t made a penny from it, plus a screen version faded out. However, for 16 years readers have kept discovering it and are still reaching out to me. The book is not so much about a boat as it is about a specific place and time — Montauk, 1951 — that fewer and fewer people have experienced.

I hope you will join me next Wednesday, September 1, the actual 70th anniversary of the Pelican disaster, at the Montauk Lighthouse at 6.30 p.m., when Bryan Boyhan, publisher emeritus of the Sag Harbor Express, and I will discuss “Dark Noon.” The talk is free and there might even be a handful of copies available.