Fiction writer, performer and off-beat humorist Iris Smyles, though she hails from Long Island, refuses (most of the time) to name the burb. Don’t look to bios and interviews in print or online to find out more.

The 2013 documentary “At Home with Iris Smyles,” by filmmaker Michael Almereyda and co-starring her good friend and mentor, the author and painter Frederic Tuten, an older arts original whom the 40-something Smyles cites on occasion as her secretary or son, keeps her presence straight-faced surreal. And don’t expect personal info from Alec Baldwin’s August 2016 lunch chat with her, as East Hampton Guild Hall’s first writer-in-residence.

Smyles’s editor and colleagues at The East Hampton Star — where she worked for a while, playing in the 2018 Artists and Writers Softball game — seem content to let her work speak for her, as do the celebrities who provided blurbs for her earlier books, “Iris Has Free Time” and “Dating Tips for the Unemployed” (a semi-finalist for the 2017 Thurber Prize for American Humor), though what they say shows her loony influence. “Similar to War and Peace, only much funnier and shorter” (actor and comedian Martin Mull). “I love this book but I wish it had more dogs in it” (The New Yorker humorist Patricia Marx).

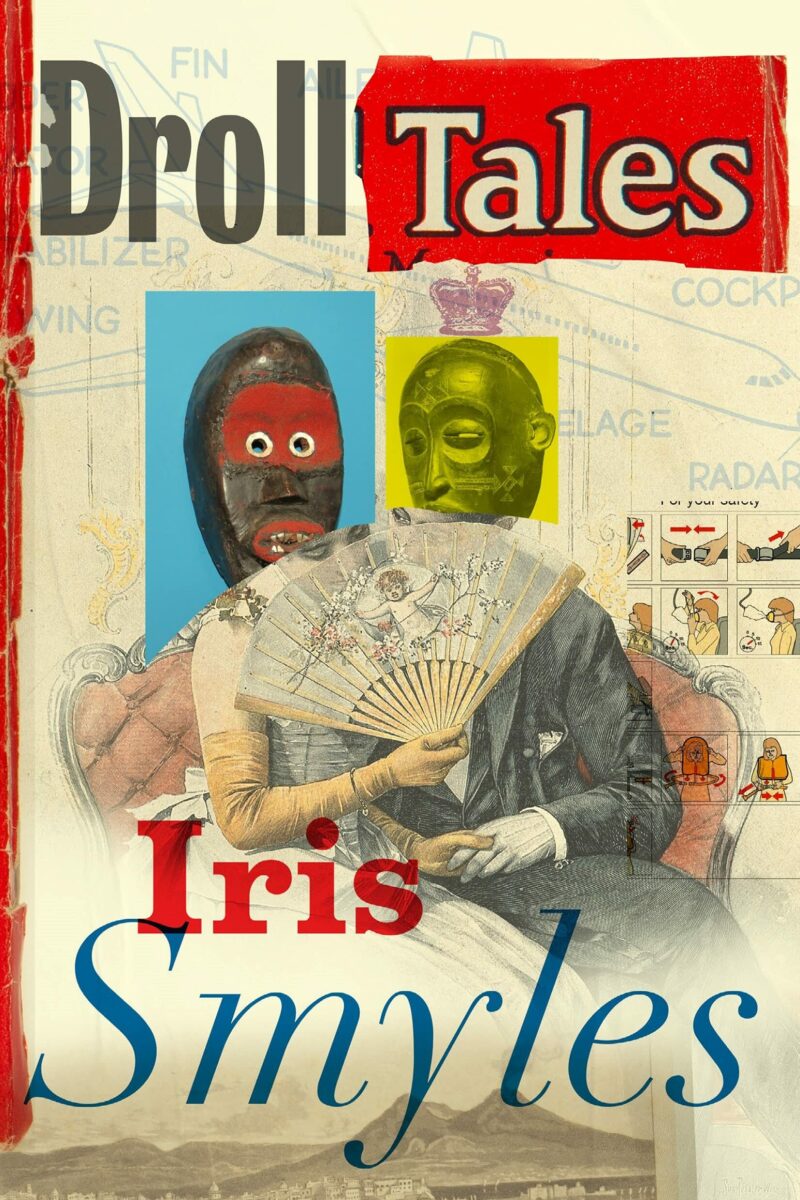

And now comes “Droll Tales,” a collection of 14 tenuously linked stories that move from the oddball to the super oddball.

The creative cleverness starts with a note to Dear Reader about the darkness of life as painful, confusing and lonely but also “fun, beautiful and, briefly ours.” The next page is a one-paragraph take-off on Zeno’s Paradox about never being able to complete a distance, and that is preceded by a three-page “glossary of terms not found in this book.” The list, in no particular order, or disorder, begins with “soufflettic,” which means “to move like a soufflé,” and ends with “lemon meringue” — “to move like a whipped dessert.” Metaphysics? “A branch of science in which you sign up for exercise classes and don’t go.” And matter? “Someone who is more like Matt than Matt is.” And then there’s “Contemporary Grammar,” a quiet story of romantic heartbreak told as 23 sentence diagrams by a fifth-grader on a grammar test. In another story, a character explains his “pre-Copernican attitude toward weather, how he believed it revolved around him.”

The word “droll” aptly captures the lives Smyles briefly features in her stories, including at times a character named Iris, who sometimes is part of the action or just provides asides, such as noting that between (often nonpaying) jobs, she’s translating Mallarmé into Pig Latin. At the heart of the Smyles’s style is non sequitur, fantasy, outrageous punning, left-hanging observations, illusions funny and sad. In “The Autobiography of Gertrude Stein” she recounts how she decided to make her apartment into a salon like Stein’s in Paris, but “with fewer omelets.” It’s where she edits the manuscripts of her good friend Jacob by crossing out superfluous letters, but leaving the “c” in his name.

The first story, “Medusa’s Garden,” stars an Iris character who works alone and in concert and competition in mounting tableaux vivants. The last tale follows a dentist whose wife is leaving him who meets a group of disparate characters at the Oyster Bar in Grand Central Station and with them enters a dreamlike underground, weird as it is comforting.

It’s her intelligence and tone that make Smyles an enchanting writer — she’s ironic, funny, compassionate, critical (especially of intellectual and artistic pretense). She deliciously sends up self-serving lit crit and nervous pretention. Asked at a party what’s she’s working on, she says a novel with a main character who’s “an amateur phlebotomist living in New Mexico.” Amateur? He collects blood samples “in a nonprofessional capacity.” “Another voice is overheard: “It’s called ‘Jaws in Venice.’ It’s like ‘Death in Venice’ but with a shark.” And another: “It’s a novel of ideas, but with recipes.”

A drunken, spacey party scene can suddenly shift — an observation of snow, a maze of city streets that makes the narrator think of dreams and loss. She’s riding somewhere in a taxi with two friends asleep in the back seat, “and behind them, through the back window, whatever was the night.” That “whatever” — a tender rhythmic riff on Fitzgerald.

A bit much? Perhaps if taken all at once, but for sure, Iris Smyles is an original, planting herself squarely between parody and homage, ridicule and empathy. She’s an artist of the subversive and surreal, who would have and hold on to what’s left in our fractured world of the humane and the artistic.