Among the appealing aspects of a photograph is what it can tell us about ourselves.

Our style, our appearance, the experiences we share, and moments of intimacy and honesty that are suddenly history the instant a shutter clicks.

And while the camera can mechanically record these pieces of our past, it is the intent and imagination of the photographer that decides what and how the images are to be remembered.

At the turn of the 19th into the 20th century, with the industrial revolution pressing hard on otherwise rural and agrarian communities, one East End photographer turned his lens on the communities where he grew up and sensed were about to change: A Sag Harbor that relied on shipping and the waterfront to drive its economy; an East Hampton where windmills still ground grain for farmers and families; and a Montauk that was awash in vast acres of pastureland that continued to feed the livestock of much of the South Fork.

William Wallace Tooker was born and raised in Sag Harbor, but he roamed much of the South Fork and, as an amateur photographer, captured much of what defined the region at the time. A unique collection of about 88 glass plate negatives that Tooker produced was passed from his hands down through a caretaker, and ultimately to a former Montauk man who has owned them for nearly 50 years. For the first time, a selection of 30 photos from that Tooker collection is being exhibited at the Sag Harbor Whaling and Historical Museum, and they give 21st century viewers a look at a moment in time before the changing world took hold of the East End of Long Island.

“I think Tooker was an intellectual and saw the emergence of the industrial age moving through, and these old houses and windmills disappearing,” said Kevin McCann, who has owned the Tooker collection since 1976. “He was a purpose driven photographer.”

While well composed, many of Tooker’s photographs have a sense of trying to capture a moment or a story rather than a formal portrait. In that regard, it’s as if the photographer is speaking to the viewer from that far off place saying: “Here, this is what we were about.”

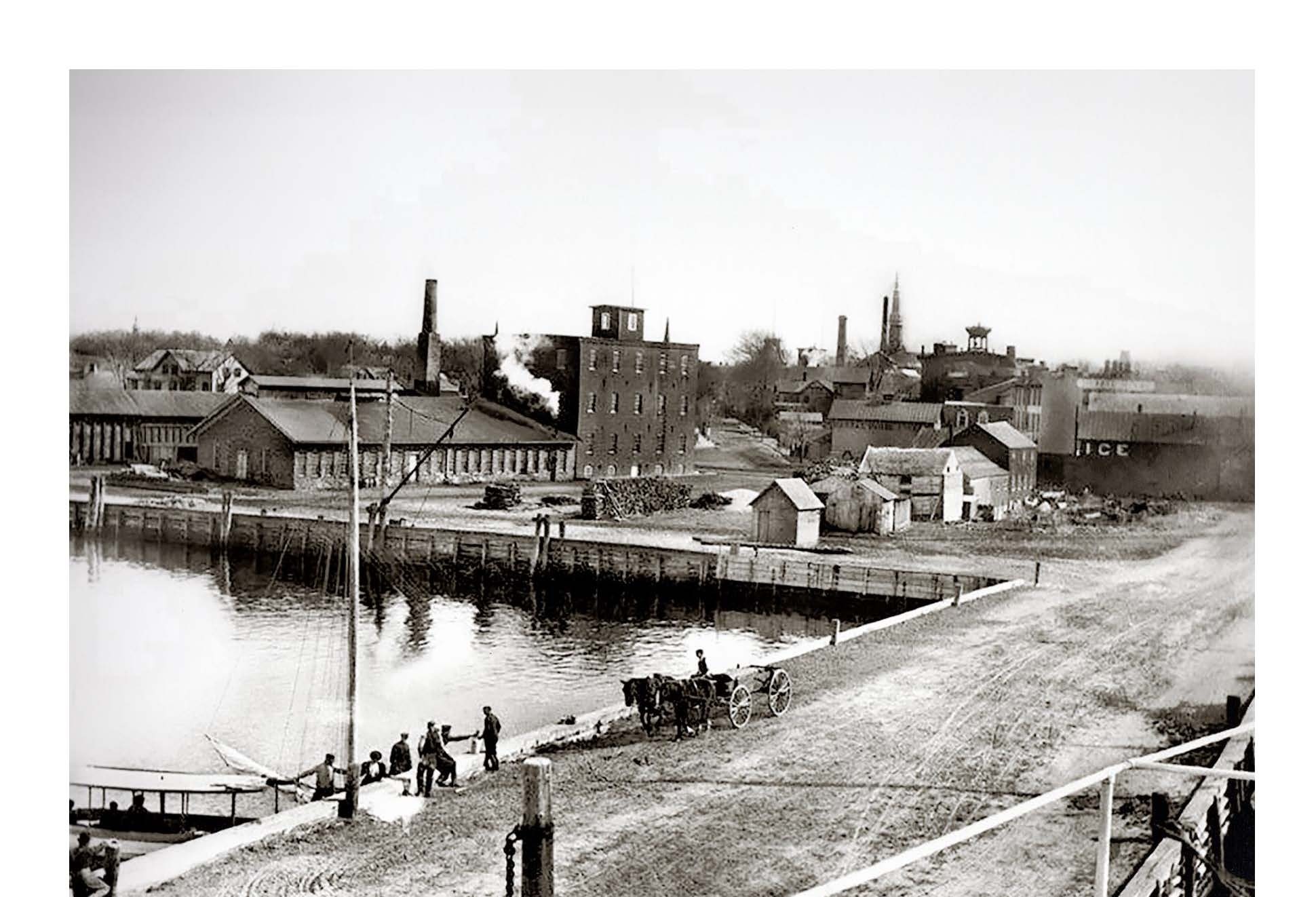

Two images along the Sag Harbor waterfront in the museum’s exhibit underscore the commercial nature of the village at the time, and indeed Long Wharf does not appear as a particularly hospitable place, as it is today. The deck is packed dirt, there is a haphazard array of small buildings and the overwhelming sense is that this is a no-nonsense place for business.

“That’s the view you got when you entered the village from the water,” said Richard Doctorow, the museum’s director and curator of the Tooker exhibit. “These are portraits, but not of people. They are portraits of the village. You get the sense that the village was a blue-collar town.

“Down by the wharf, today we wonder, why does this look the way it does?” he continued. “Well, down by the wharf is where you worked. It’s not a scenic or beautiful place, necessarily. But a place where oil was processed. Where there were workshops.”

It was such a busy place that at one time there were two wharves built out along Bay Street, or what was once called East Water Street. There was the familiar Long Wharf, which is represented in a photograph looking down on the wharf from the top deck of a steamship. You can see in the foreground a small party disembarking from what appears to be an excursion boat, while a team of horses and a buckboard wait. It is not a pretty place, and there are warehouses beyond the bulkhead, stacks of lumber or cordwood, a chimney rises several stories and the detritus of the shipping industry litters the area. In the background, you can pick out the steeples from the Methodist Church and the Old Whalers Church along the skyline, as well as the Municipal Building, and in the foreground the four-story brick building which today is occupied by Malloy Enterprises.

But then there is the photograph of the other wharf, which Doctorow tells us was built a bit further east along the harbor. At the center is the warehouse of the Montauk Steamboat Company, which was the chief tenant of the wharf, built as the Maidstone wharf, and who engaged in a rate pricing war with the Long Island Rail Road Company, which installed a competitive steamboat line on its Long Wharf. In the photo is one of the several steamships that took passengers and cargo between Sag Harbor and New London, or Brooklyn or New York City. Horses and a couple of carriages wait for passengers, or goods to carry up to shops on Main Street or even into Bridgehampton.

On the opposite side of the wharf, a set of steel rails rises up to the end of the pier. Here, said Doctorow, dollies would have been used to unload coal for heating or to power the factories that were beginning to emerge in the village.

There are also pictures of Sag Harbor in the snow, with a couple of sleighs pulled by horses, and more children in the snow packed streets than vehicles of any sort. One photo, in fact, includes Tooker’s own pharmacy, near the corner of Main and Spring streets.

There’s the Christ Episcopal Church and a few village houses, one showing the aged inhabitants sitting in the backyard on straight back chairs, the doors to the colonial house thrown open. You can imagine it’s a sweltering day, and the open doors are to help ventilate a stifling house, but still the couple wears long sleeves and the man and woman are fully buttoned up.

And while many of the photos are of Sag Harbor, there is representation from much of the South Fork, including some of its windmills — the full collection includes images of all 13 windmills that existed at the time — the Montauk Lighthouse and even a photograph of Shelter Island’s Manhansett House hotel, an imposing and spectacular structure that once overlooked Shelter Island Sound, but burned in the early 20th century. In the photo, women in fashionable clothes stroll a broad boardwalk out to a dock where the masts of sailboats peek up above the bulkhead. A man looks on as a young couple kisses. And the hotel rises up behind them.

Perhaps one of the most interesting photos in the collection, and one that McCann has devoted a good amount of time researching, is of a whale that had beached in Sagaponack in 1891. A small crowd of men and two young boys have gathered around and on top of the whale and it is clear that work is about to begin carving the blubber off the beast.

The story, argues McCann, goes deeper than just an image of a whale about to be carved up; which, by the time this photo was taken, would have been an unusual sight on a Sagaponack beach. It is, says McCann, the story of the ending of an era that stretches back to the earliest times of human civilization on the East End of Long Island, and a moment in time when the relationship between the whale and man — both Native American and the European inheritors — is its most intimate.

In a paper he prepared on the significance of this one photograph, McCann writes:

“To tell this pertinent and valuable story a photograph needs three essential and distinct components; a native Indian, a beached whale and a white European settler together in a single image harvesting a beached whale. It’s this relationship that tells the story of one of America’s earliest economic triumphs. The opportunity to photograph the three remarkable components was from 1840 to maybe 1900 which is the tail-end of the centuries-old relationship.”

Further, McCann imagines the day and Tooker’s efforts, and even the situation portrayed in the photograph and its players.

“[Tooker] recognized he was living in a major transitional moment in history and purposely photographed what he thought should be memorialized,” writes McCann. “When he learned there was a large beached whale in Sagaponack he realized it was a chance to capture this vanishing phenomena for posterity, as whales too were disappearing and could become extinct. It was a photographic opportunity that couldn’t wait. In order to take the photograph, he would have to leave his pharmacy, pack his bulky camera and sizeable tripod, take a horse and buggy eight miles out, walk down the sandy beach, take a single photograph on a glass plate and then ride eight miles back to Sag Harbor. He would then have to go through the painstakingly detailed process of developing, processing and printing the image. No other photographer or artist chronicled the event and he did not publish or sell this image. Tooker seized the opportunity to record it for the historical record.”

In an effort to complete the narrative, McCann said in a recent interview, he is working on identifying the people in the image. He is convinced there are a couple of laborers who are Native Americans, either Shinnecock or Montaukett, who were probably the only ones skilled to deal with the animal, plus one or two members of the nearby lifesaving station at Georgica. Also, there is the European man who was the one who McCann believes “pulled the permit” claiming ownership of the whale. The two boys would be his sons.

The image, likely the most important in the exhibit from a cultural history standpoint, will also be the largest.

McCann, who grew up in Montauk and developed an interest in recording the history of his native hamlet, now lives in California. But as a young man, his interest in photography fueled in part by the photographer Peter Beard, he worked in a windmill studio Beard had acquired and had moved to his oceanfront property high on Montauk’s bluffs.

In 1976, McCann learned about the availability of the collection of glass plate negatives created by Tooker, which also featured many scenes of Montauk. Tooker, in addition to being a pharmacist and a photographer, was also an “Algonquinist,” a term he coined himself — a student of the language and culture of the Algonquin tribes, like the Shinnecock and the Montaukett. In fact, he may be best known for his book “Indian Place Names on Long Island,” a volume that contains over 500 names and words translated from the Algonquin language. While many authorities question the accuracy of some of the translations, it is still viewed as an important volume on the island’s Native history.

But the book may never have been completed if it had not been for the benefactress Margaret Olivia Slocum Sage. McCann suffered from debilitating arthritis and was not able to work without help. Sage came to his aid to fund a nurse to act as his caretaker. That caretaker was Mildred Overton, a nurse who, as it turned out, had an interest in photography.

Tooker was so taken with Overton, as McCann tells it, that he bequeathed to her his collection of 88 glass negatives. After her death, her brother, John Overton wound up with the collection

“I remember sitting across the table from John Overton in his kitchen,” McCann said recently. “He sized me up and said, ‘I know I could probably get more for these photographs.’” But instead sold them to the young man from Montauk.

There is no small amount of irony in the path the photos have taken.

If it wasn’t for Mrs. Sage, Tooker would never have met Mildred Overton, who would never have received the collection of photographs to pass to her brother, who would never have sold them to McCann, who would not have been able to exhibit them at the Whaling Museum.

The museum, by the way, was, in fact, Mrs. Sage’s home when she lived in Sag Harbor early in the 20th century. She also paid to build the John Jermain Memorial Library, Pierson High School and Mashashimuet Park.

It’s interesting, said McCann, reflecting on the route the Tooker photographs have taken, and noting they would wind up in the former home of the photographer’s benefactor.

“What goes around comes around.”

“A Pleasure To The Eye” an exhibit of photographs of Sag Harbor and other East End locations taken circa 1895 by Sag Harbor native William Wallace Tooker are on view at the Sag Harbor Whaling and Historical Museum, 200 Main Street, Sag Harbor. The museum is open Thursday to Sunday 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. (last entry 4 p.m.), with staggered entry for up to eight guests per party. For more information, visit sagharborwhalingmuseum.org.