By Joan Baum

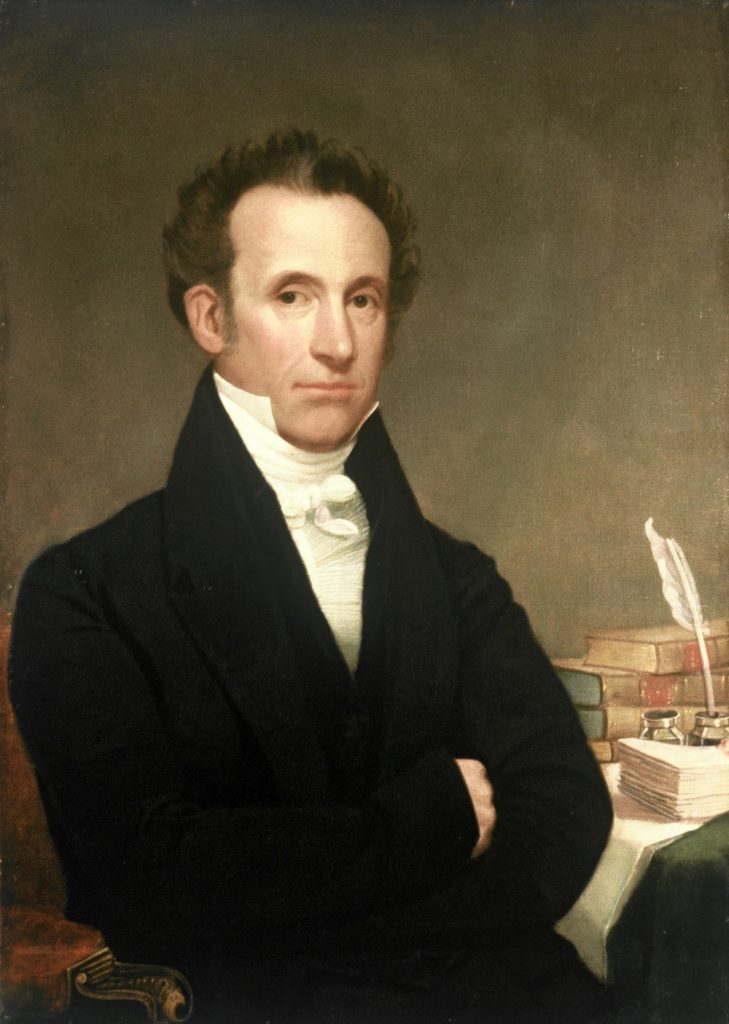

Although historian Ann Sandford urges appreciation for her distant Bridgehampton-born second cousin, five generations removed, Nathan Sanford (1777-1838) – “he was in a hurry, she writes, so he dropped the ‘d’” — her academic, yet accessible monograph on his life and career, “Reluctant Reformer,” satisfies two main reasons for publishing a biography: new or unknown information about an influential figure at an important time in history, and a timely and significant theme that may prompt readers to reevaluate personal motives and political effects past and present.

Nathan Sanford affected political, economic and judicial policy at a critical time in post-Revolutionary America, especially regarding voting rights and slavery. Like Sanford, Ann Sandford is Eastern Long Island born and bred, with Bridgehampton roots that go back ten generations. “Oh, the wonderful Clinton Academy,” she says, where Sanford studied before going on to Yale and the prestigious Litchfield School of Law. Talk about local boy makes good: appointed by President Jefferson to be a federal attorney for New York, which meant the entire state, Sanford worked alongside leading Republican factional leaders such as DeWitt Clinton, Aaron Burr, Martin Van Buren.

Sandford, too, went to local schools and then to Elmira College (founded in 1855), but when she began graduate work at NYU, she says she wanted to broaden her research area and wound up concentrating on early modern European history, writing a book on the ancient southern French city of Nimes. Her work sharpened her appreciation of how a local town could influence larger regions (“did you know, that the word denim traces to Nimes?”). Subsequent scholarship took the Sagaponack resident back to her roots. Sandford is the author of “Grandfather Lived Here: The Transformation of Bridgehampton, New York, 1870-1970 (2006).” It was only after years of working on “Reluctant Reformer” that she came upon a section on New York State history in the Harvard archives that she discovered his role in the New York State constitutional convention of 1821 and realized “that much of what I had heard as a child about a famous relative could be true.” The rest, as they say, is history.

When he died in 1838, Nathan Sanford left behind more than 1,300 volumes and was responsible for helping to develop a national law library that eventually became the Library of Congress. So how come he is (until now) relatively unknown? Sandford speculates: he never held national office or an executive position in the public eye and because of pulmonary problems that plagued him for 30 years was never an effective orator at a time eloquence counted. He also left no significant diaries, correspondence or record of political thought, though thank goodness “he had good handwriting,” a boon for any researcher.

On Saturday, January 27 at the Hampton Library in Bridgehampton, Sandford will talk about that post-Revolutionary time and about Nathan Sanford who had a “lasting impact” on the young republic in New York City, New York State and the nation. His achievements, she believes, owe something to his rural East End upbringing where a sense of community informed his views about voting rights and universal suffrage, and opposing slavery. His contributions to reform in the New York State court system, she notes, began in Southampton with a famous case about a fox that turned on issues of property and possession and went on to be heard in the state Court of Appeals.

Sanford’s personal and professional life as a lawyer with abiding interest in central banking, paper money, libel law and all aspects of “political economy” put him occasionally at odds with his professed opposition to slavery and support of universal manhood suffrage and popular voting for presidential elections. He was given to compromise, but it is just that ambiguity that marks him as an interesting political figure. He liked wealth and the social status associated with it. In later life he built himself a luxurious mansion (“Sanford’s Folly”) in Flushing, a three-story Greek Revival style house with “park-like grounds.” “He had principles,” Sandford says, but he also knew the practicalities of being a politician. He counted votes, he appreciated small victories and close losses. Like Henry Clay, whose presidential ticket he joined as vice president in 1824, he would compromise, though not as Clay did. Sanford rejected the Missouri Compromise (it passed) that admitted the state as a slave state, while Maine was admitted free.

If Nathan Sanford was a “reluctant” reformer — “I liked the ring of that for a title,” Ann Sandford laughs — he can still be, for all his wealth and powerful crony connections, considered a reformer. Some of his legal work did result in restricting male suffrage and removing Native Americans from ancestral lands, but he clearly “contributed to the expansion of democratic rights such as the election of presidential electors in all states (defeated) and responsive government,” says Sandford.

Sandford’s book is no hagiography. She acknowledges her distant cousin’s “disagreeable temperament” and “arrogance,” even quoting 18th century jurist James Kent, the first Professor of Law at Columbia, who called Sanford a “hardy, avaricious, heartless Demagogue.” But as the last paragraph of Sandford’s book puts it, Nathan Sanford was “a mix of adherence to [ideal] principle and unbounded personal ambition.” The key word here is “principle.” How contradictory and compelling political, social and economic forces interacted and how they governed Sanford’s 60-year life are questions of increasing ethical and psychological concern today.

“Nathan Sanford was indeed a ‘reluctant’ reformer [who] steadfastly sought influence through politics and government service, while he participated in the idealism of republicanism and the opportunistic culture of his day.” This is a relatively short though dense, detailed, fact-filled account that should be read in stages. But it should be read.

"Reluctant Reformer: Nathan Sanford in the Era of the Early Republic" (SUNY Press, 204 pp., $29.95) The book has extensive notes and bibliography. Slides will accompany the talk, which will take place at The Hampton Library, 2478 Main Street in Bridgehampton, on Saturday, January 27 at 11 a.m. For more information, visit hamptonlibrary.org.