June 16 has special meaning to a special group of literary fans, and “Bloomsday” will have even more significance this year.

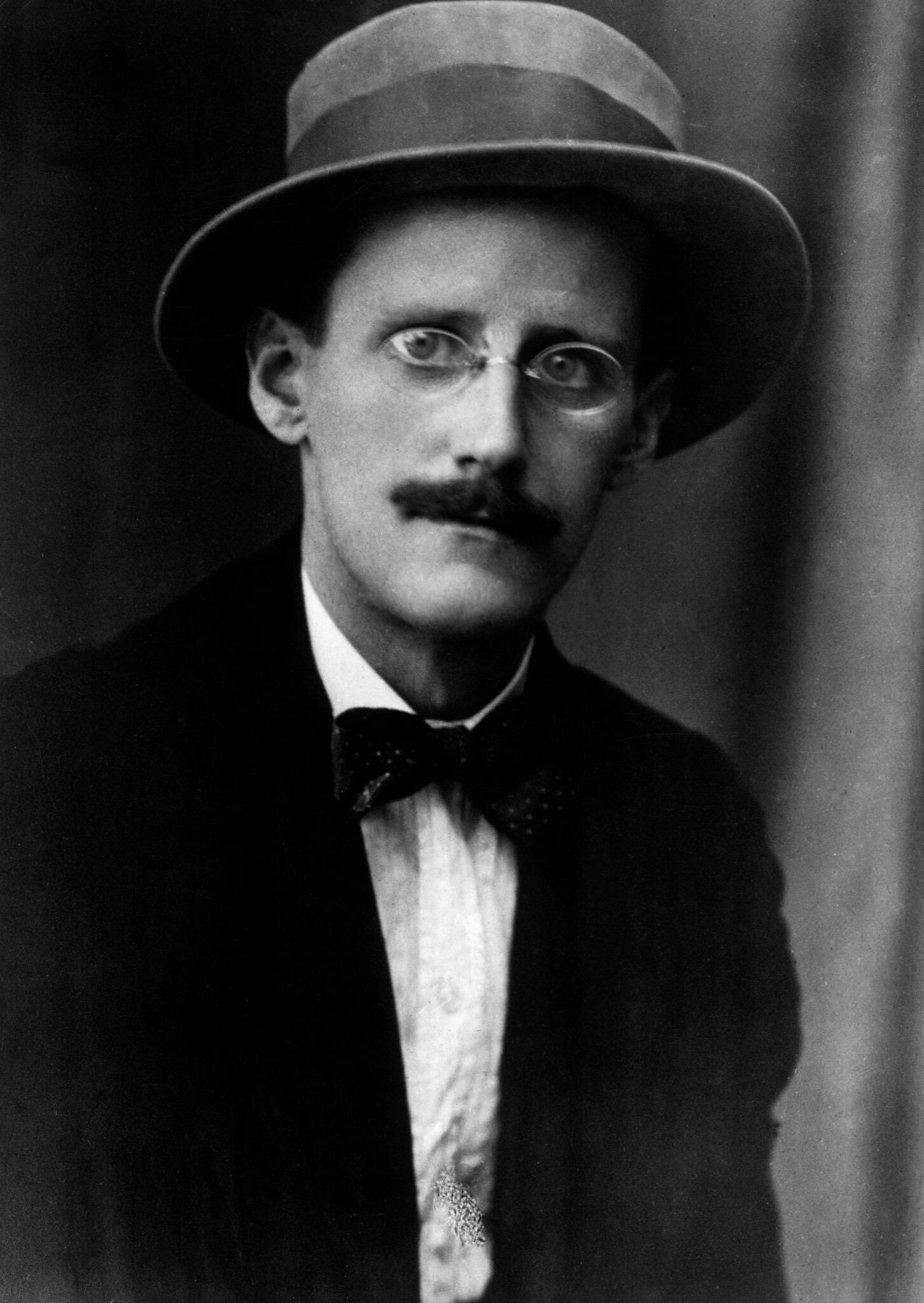

James Joyce’s masterwork, “Ulysses,” just turned 100: It was published in its complete form by a small Paris press, Shakespeare & Company, on Joyce’s 40th birthday, February 2, 1922. So this year’s annual Bloomsday — the book depicts a single day in Dublin, Ireland, June 16, 1904, as seen through the eyes of a large cast of characters, including Leopold Bloom — is truly something to celebrate.

“Ulysses” was at the very top of several respected lists of the greatest novels of the 20th century. It stirs up great emotions in its fans — some of whom will gather at Sag Harbor’s John Jermain Library on the evening of June 16 for a roundtable appreciation hosted by Canio’s Cultural Cafe.

But you probably haven’t read it. Have you?

Here are 10 reasons you should.

• It’s not as difficult as everyone says.

The adjective “unreadable” has been applied to “Ulysses” by detractors. But that’s nonsense. In a short letter written a month after its publication, Ernest Hemingway wrote in a letter to a friend, “Joyce has a most goddamn wonderful book.”

And it is. Joyce set out to capture Dublin society by focusing on a single day, bouncing focus from character to character, and listening in to their private thoughts and deepest secrets via internal monologue.

Certainly, there are challenges. Dublin in 1904 was a different time and place, and many of the references are lost on a modern audience. But Joyce’s prose was magnificent, and the book is not only readable, it’s goddamn wonderful. It’s a book anyone can enjoy.

• It’s every bit as difficult as everyone says.

Okay, let’s be honest: Joyce wrote the first truly modern novel, and it remains a tricky read. There are some chapters — Chapter 3, which is a long internal monologue while a main character, Stephen Dedalus, walks on Sandymount Strand — is known as the “sandtrap,” because a lot of readers never get past it. It was experimental in 1922, and it’s still a bit of a lift today.

That’s not mentioning other chapters, which attempt to capture music in language, suddenly switch to playwriting, or, in the final chapter, “Penelope,” do a deep, mostly unpunctuated dive into the mind of a half-sleeping woman, Bloom’s wife, Molly. Skim those chapters, and the word “unreadable” won’t seem out of bounds.

But that’s not at all the case. This is a book that has plenty of joy to give a casual reader, who can, frankly, skip over the harder sections if they’re too challenging. Anyone who is interested can find a world of supporting literature to help unlock the secrets of the book, and find a remarkable bounty. It’s a book that rewards the effort to dig in deeper.

• It’s the ultimate puzzle book.

Joyce was brilliant, but he also was playful. Famously, he said of “Ulysses”: “I’ve put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant, and that’s the only way of insuring one’s immortality.”

He’s not wrong. The entire book uses Homer’s “Odyssey” as the structure, superimposed on the lives of 1904 Dublin people. Finding the correlations is easy and fun. (The man with the eye patch in the pub? Think: Cyclops.) His contemporary, Richard Ellmann, discussed the novel with Joyce at length and might be the best guide, and he was generous with his energy.

Having a guide helps. Every chapter has a different style of writing, a literary technique. A different color as its theme. An organ in the body. An art form. A symbol. Deciphering the riddles is incredibly satisfying. But, yes, it’s a puzzle.

I will say this: I have never stopped reading “Ulysses” and the library of supporting literature, and I never plan to.

• It’s gorgeous writing.

Trying to defend the complicated parts of the book mean overlooking something essential: It is a joy to read. Whether he’s describing people or emotions, or somehow capturing better than anyone ever has how that little voice in your head actually speaks to you, his prose is flawless. When he gets playing around with words, it’s fun, even when you can’t keep up. (He hit the turbo boosters with “Finnegans Wake” at the end of his writing career and pulled away from almost everyone.)

• The “impenetrable” parts? They’re beautiful to look at on pages.

Seriously. This novel looks like no other book. You turn the page after finishing a chapter, and you genuinely have no idea where you’ll go next.

• It’s the best audiobook ever.

Or, you know what? Don’t look at the pages at all. Just go get the audiobook.

The one to get is by Naxos AudioBooks, narrated by Jim Norton and, as Molly Bloom, Marcella Riordan. (A man simply could not do any justice to the “Penelope” chapter.) Quite honestly, the audiobook opens “Ulysses” up: So much of the book is about the music of the words, sometimes quite literally, and hearing an informed narrator suddenly burst into song, the lyrics from 1904, can be beyond enlightening.

• The characters are real people, and they transcend their times.

A book about life in 1904 should feel a little foreign. And it does. But by holding back nothing — the book famously discusses virtually every bodily function and stares unblinkingly at sexuality, which is why it was labeled a “dirty” book that should be banned — it quickly becomes evident that, while clothes, speech and habits have changed, basic humanity is the same down through the ages. There is nothing outdated about “Ulysses.”

• It makes everyday life heroic.

Don’t miss the important message Joyce was sending by building his depiction of 1904 Dublin on the framework of the ultimate story of heroic struggle. Some call “Ulysses” “mock heroic” — but I think that misses the point. Everyone is the hero of his or her own story, and just living life, then or now, is heroic.

• It’s terrifying, hilarious, shocking and gutting.

Even 100 years later, “Ulysses” can shock. It’s also terribly funny when it wants to be. There are scenes that rival David Lynch. And there are the little moments, the kind we experience every day, that drop like pearls and just destroy you.

• The “Penelope” chapter is the greatest thing ever written.

There, I said it. At least in the English language, I have never read anything remotely like it, and nothing that is so affecting. It is the greatest ending to a book ever, intoxicating in its steady flow of half-asleep thoughts and revelatory of the complexity of women — but, really, of us all. If Joyce had only written that chapter, he would still have a place in the pantheon.

Lucky for us, he wrote more. Now you just need to go on your own “Odyssey” of discovery. It’s worth the trip.

Joseph Shaw is executive editor of The Express News Group.

On Thursday, June 16, at 6 p.m. “Bloomsday: Ulysses Demystified” will be offered by Canio’s Cultural Cafe in the rotunda at the Jermain Library, 201 Main Street, Sag Harbor. Celebrate the 100th anniversary of James Joyce’s modern classic with a lively discussion and selected readings. Moderated by Joe Shaw of The Express News Group also taking part will be literary critic Joan Baum and actors Paul McIsaac and Kate Mueth and impresario Peter Walsh. Registration required at johnjermain.org.

In the meantime, to prepare for the library event, watch the film “In Bed with Ulysses” by Alan Adelson and Kate Taverna, starring local actor Paul McIsaac, online only from June 9 to 16. There’s a suggested $10 donation for the Canio’s Cultural Cafe and the filmmakers. Visit canios.wordpress.com for details.