E.T. Williams Jr. is a young 81. But he is, self-admittedly, in the throes of his last act.

It began in the mid-1990s, at a cocktail party in Sag Harbor, where the successful banker-turned-real-estate-developer found himself captivated and moved by a painting hanging on his friend’s wall. His wife, Auldlyn—and partner in championing African-American art—felt the same way.

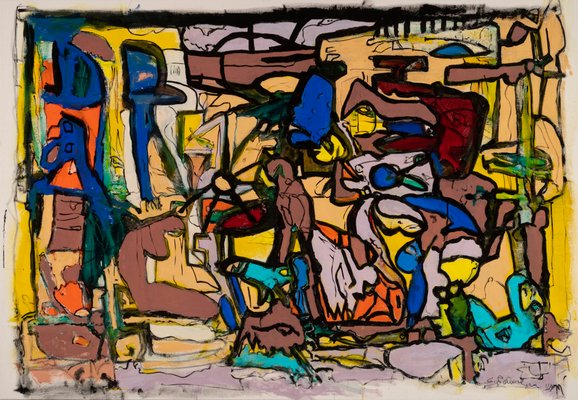

“The first thing that struck us was the colors,” Mr. Williams recalled. “They were very vivid and we liked his movement in his pictures, and the lines. We could see a lot of jazz in his expressions.”

They would soon learn the painter’s name, Claude Lawrence—a Chicago-based jazz musician and borderline recluse who had managed to fly under the art world’s radar for over three decades.

Until now.

Over the last six years, and largely due to Mr. Williams’ efforts, Mr. Lawrence has entered 32 museum collections, and his first East End show will open on Friday night at Keyes Gallery, located at 53 Main Street in Sag Harbor—not far from where the artist spent two influential periods painting and living in the village.

“We have a lot of collectors who have pre-bought for this show, which has not really happened that much,” gallery owner Julie Keyes said. “People are coming forward and asking to go through things and are reserving things. It’s got a huge buzz. Museums are not stupid; they buy these things because they know how fantastic it is.”

Born in 1944, Mr. Lawrence is a product of South Side Chicago—a city that was on the forefront of the Civil Rights Movement with a burgeoning arts, music and cultural scene, and jazz clubs of international repute. He picked up the tenor saxophone as a high school student and, after playing the Chicago jazz club circuit, in 1964 he set his sights on New York.

It was the first of his many moves to New York, where he maintained a career as a musician and, by the 1980s, as a serious painter, too. The art world then was over-hyped, over-saturated and unsupportive of African-Americans, according to artist and critic George Negroponte, who wrote an introduction to the Lawrence show.

“I know that the African-American artists were not having a very easy time. They didn’t have any support whatsoever,” he explained from his home in East Hampton. “The so-called ‘correction’ in this oversight by the art world really started to take place about 10 years ago, and it’s very gradually built up to the point where a number of African-American artists from the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s have had a lot more exposure.

“Mr. Lawrence has had some exposure, but not too much, and I’m so curious to see what happens,” he added. “I have a feeling people will gravitate toward this work because it’s very lively, very alive.”

The Sag Harbor show quite possibly marks the first major solo exhibition of an African-American artist in the village, if not across the entire the East End, according to Mr. Williams.

“It’s really quite unfortunate, but that’s the reality of what’s happened,” he said. “Of course, in today’s world, everybody’s pretty much equal and a lot of the museums are playing catch-up. And as a result of playing catch-up, Claude Lawrence got in the mix—he sold me his collection and I know a lot of curators.”

In 2013, three of Mr. Lawrence’s paintings were accepted into the permanent collection of the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill. A year later, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Department of Modern and Contemporary Art followed suit. Then came the Studio Museum in Harlem, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the National African American Museum and Cultural Center, the National Gallery of Art, and dozens more, as well as private collectors.

But Mr. Lawrence still cowered from the spotlight. In 2016, he made a public appearance and gave an alto saxophone performance for the opening of “Modern Heroics: 75 Years of African-American Expressionism” at the Newark Museum, where his work was also on view.

“He’s a jazz musician and he’s always thinking about jazz and improvisation, and I think he prefers in many ways to be alone,” Mr. Williams said. “He’s not a person that likes to be around a lot of people because he’s very intense, in terms of what he’s doing. He gets even more so when he gets some ideas of the painting he wants to do. He doesn’t want to be bothered by anybody. He just wants to go into a room and talk to the paint and the brushes.”

From what Negroponte can gather, that is precisely what Mr. Lawrence did during his two stints in Sag Harbor, from 1994 to 1998 and 2001 to 2006. The latter was a “charged moment” for the artist, he said, one that led to “this extraordinary body of work in the last 20 years—really, really extraordinary.”

“There’s a DNA to this work that keeps developing and developing,” Negroponte said. “You could say that he is just simply growing up as a painter, but I also think he found himself in the company of all kinds of elements here—whether it be the sea, the sky, the art history, the legend of East Hampton and Sag Harbor. It seemed to fuel him, and it seemed to fuel him in a way that was extremely positive.”

To have Mr. Lawrence’s first major solo show in Sag Harbor feels appropriate, Mr. Williams explained. And though he no longer considers himself to be a collector of African-American art, the endeavor has given him a “tremendous feeling of great satisfaction,” he said.

This is his legacy, as he sees it.

“We really stopped collecting around six years ago, and started giving work to museums,” he said. “That’s how a lot of the museums got to see Claude Lawrence’s work and have taken his work. We have given 150 works of Claude Lawrence to 32 museums in the country. We’re very excited and very happy for him, and it’s been very rewarding for me. This is my last act, and this could really launch him to be a really major player.”

A solo show by artist Claude Lawrence will open with a reception on Friday, July 26, from 6 to 8 p.m. at Keyes Gallery, located at 53 Main Street in Sag Harbor. The show runs through August 8.