On October 1, the new animated film “The Addams Family 2” debuted in theaters and on streaming platforms across the country. Though the film’s reviews are decidedly mixed, there is agreement on one thing — it’s hard to imagine a franchise with the kind of staying power of the Addams Family, which began long before the ooky, kooky bunch made their first big screen appearance in 1991 or became the subject of a Broadway musical in 2010.

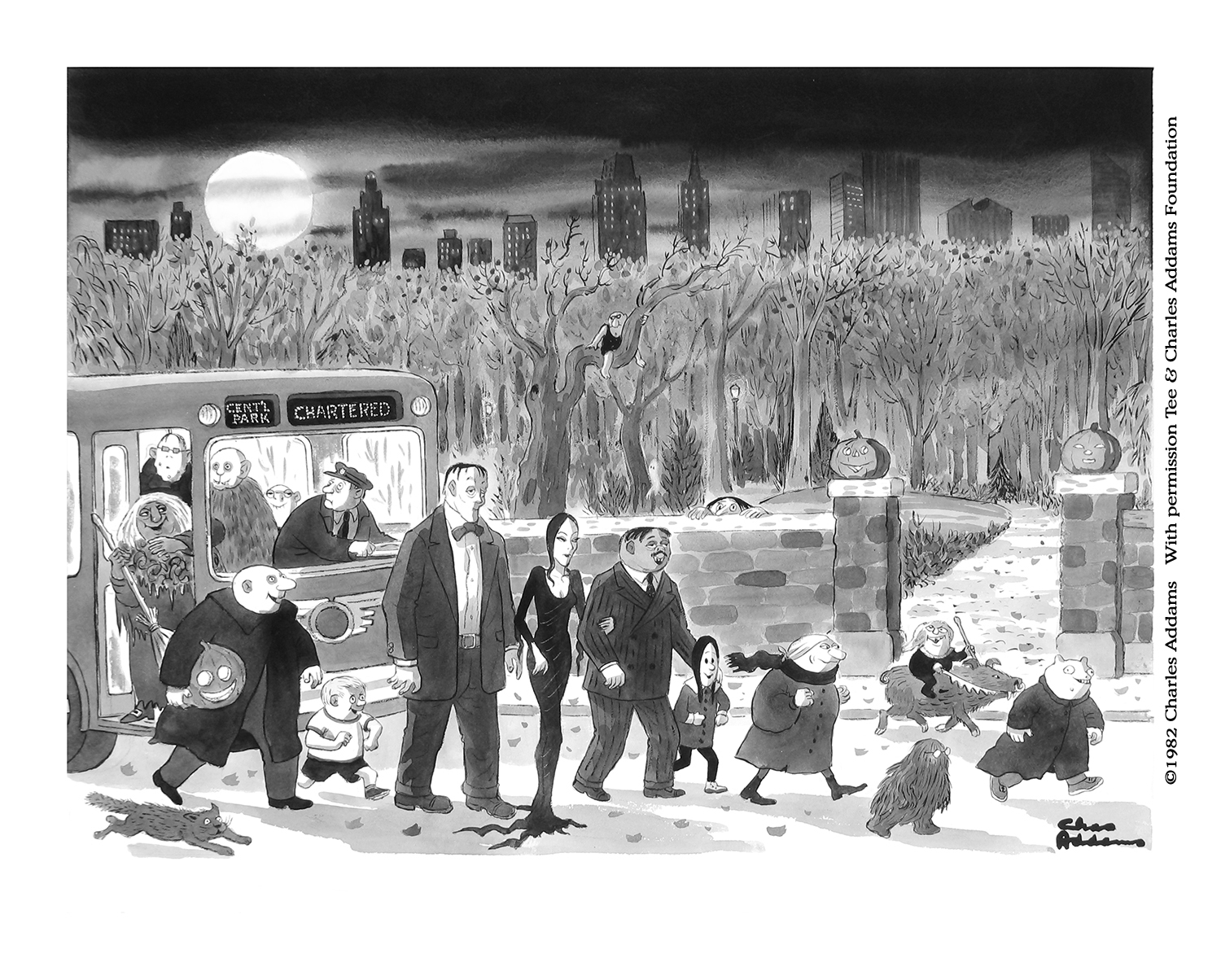

In fact, it all began way back in 1938 with a black and white, single-panel cartoon created by Charles Addams for the New Yorker magazine. The recurring characters featured an unnamed family of macabre misfits, who, in the 1960s, became the stars of a wildly successful sitcom beloved by Baby Boomers. And while no one is exactly sure of the real-life location that served as inspiration for the famed tumble-down gothic mansion Addams depicted in his cartoons (some say it was in his native Westfield, New Jersey), because the truth of the matter is, he never drew the house the same way twice, when it came to his own abode, Addams was happily ensconced in a rambling, ranch-style bungalow full of light and set on 4.5 acres on a swamp in Sagaponack. That’s where he and his third wife, Marilyn “Tee” Addams (nee Matthews), lived from 1985 until his death in 1988. Prior to their move to Sagaponack, Tee and Charles Addams lived in Tee’s house in Water Mill, and as far back as the 1940s and 1950s, Charles had rented homes in the Westhampton Beach area with his first wife, Barbara Jean Day.

Everything you’d ever want to know about the legendary cartoonist, who spent many years on the East End, can be found in Linda H. Davis’s biography “Charles Addams: A Cartoonist’s Life” (Turner Publishing). The book was originally written in 2006, and it’s being brought back into print, this time in a paperback version, to be released on October 19.

Despite being his biographer, Davis, who lives in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, never had the opportunity to meet Charles Addams in person. She hit on the idea of writing a book on him more than a decade after the cartoonist’s death. But with the blessing of Tee Addams, Davis found the support (and the material) that she needed to write the book.

“I came along in 1999. I was struggling at the time to come up with an idea for a third biography,” explained Davis, who had previously written books about author Stephen Crane and editor Katharine S. White. “I couldn’t think of a literary idea. I couldn’t write a book about Einstein because I wouldn’t understand the math. But I thought I could write about an artist or cartoonist.

“I think Charles Addams was a repressed idea,” continued Davis, who had clipped his obituary out the New York Times and filed it away for years before pulling it out again. She admits that she didn’t know much about the cartoonist prior to becoming his biographer, but had long been a fan of his work, having been about 10 years old when The Addams Family TV show first premiered.

So Davis wrote to Tee Addams with a proposal to write a book on her late husband. But after she failed to responded to her initial request, Davis reached out again, this time sending along a biographical memoir she had written for the New Yorker magazine about author E.B. White, who Davis had known for the last eight years of his life.

“She read it and immediately sent me a letter via Federal Express saying please call me and we talked on the phone,” Davis said. “It turned out that she loved biographies more than any other genre and had been wanting someone to do a biography on Charles and had been approached but didn’t think they were the right writers.

“She asked ‘When can you visit?’ So I came for an overnight. She told me later if we had not clicked at first, it wouldn’t have worked.”

But clicked they did, and Davis was off and running.

Once she launched into her subject, Davis found that the main challenge in writing about the life of Charles Addams lay in the fact that, despite the fact that he was a prolific cartoonist, he left very little behind in terms of a traditional written trail.

“There were no letters, no diaries,” Davis explained. “He did, however, have all these cartoons and kept financial records. He had a log in a spiral notebook in which he entered things, starting in 1935 when his first actual cartoon was published in the New Yorker. He kept records of every cartoon he sold, where it went and the kind of money he made for it. He also kept little date books that were helpful and revealing.”

More of Davis’s information came through interviews with those who knew Addams personally. Davis notes that she talked to some 130 people for the book, including old girlfriends and people who worked at the New Yorker who provided some wonderful anecdotes. But by far, the best source was Tee Addams herself.

“Tee was a biographer’s dream. She gave me access to everything,” Davis said. “She said, ‘I want to it to be a good biography, so don’t worry about my feelings.’ If I had to have restrictions, I couldn’t have done it. It also would’ve been a lot of harder if she had been living when I finished the book.”

Helping Davis to sort through all the archival material was H. Kevin Miserocchi, director of the Tee and Charles Addams Foundation, which is headquartered at the former home in Sagaponack. Miserocchi had first met Tee Addams through ARF, where they both volunteered, and he soon became close friends of the couple.

“Kevin was wonderful. He had organized things and found things that Tee would not have been able to find,” said Davis.

There are a lot of myths surrounding Charles Addams, including rumors that said he slept in a coffin, drank martinis with eyeballs in them, and kept a guillotine at his house. This reputation, of course, grew out of the popularity of The Addams Family, and while Davis maintains that many of the purported macabre aspects of his personality were purely for show, he did have a certain enthusiasm for a few unusual hobbies.

“He really loved those crossbows, he considered them art. They were beautifully carved, with inlays of ebony and ivory,” she said. “He loved those and some of the other things he picked up starting in the 1940s. He also got a stuffed bat, which he didn’t love so much, but he played it up. He said, ‘People expect me to be someone who needs a bat.’ Tee was fine with it.”

Though initially, it was said that Addams was not a fan of the ’60s TV show based on his cartoon characters, according to Davis, he ultimately came to appreciate what it did for his bank account. Ultimately, however, his work on the page was more important to Addams than the empire that grew up around it.

“When asked how he wanted to be remembered, he said, ‘I think as a good cartoonist,’” Davis said. “That reflects his modesty. Success never went to his head.”

So what would Charles Addams think about this newest animated film based on his characters, which were created more than 80 years ago?

“I think he would’ve been delighted with income — he died before the first feature film, so he didn’t get the money,” Davis said. “On the other hand, he might’ve been bothered by the way they’re drawn. The other thing is, so much of his work was just funny. What people tend not to realize today is that Addams’s sinister stuff is an extremely small part of it. A lot of it is sweet.”

Next week, on October 20, Davis will give a book talk in conjunction with Addamsfest, a celebration of the cartoonist’s life which is held annually in Westfield, New Jersey, his hometown.

But truth be told, the final resting place of the ashes of both Charles and Tee Addams (who died in 2002), lies in a little pet cemetery located on their Sagaponack property, situated at the edge of a proper swamp — just as it should be.