Director Oren Moverman was smart. He took the stage of Guild Hall in East Hampton on Friday night and cracked a few jokes, loosening up the Hamptons International Film Festival audience.

Then he delivered a grim warning. That was the final time they would laugh over the next two hours.

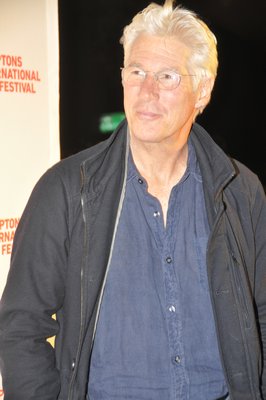

He was almost entirely correct, save for a few moments of comedic relief during his newest feature, “Time Out of Mind,” starring Richard Gere as a homeless man in Manhattan.

The audience rumbled during the closing credits, ruminating on what they just witnessed, until they were jarred from their reverie was the screen lifted, revealing HIFF Artistic Director David Nugent, Mr. Moverman and Mr. Gere seated around a table.

“It’s tough to sit after a movie like that and digest it,” Mr. Nugent said.

“We can do just that,” Mr. Moverman said. “We can sit and digest it. We don’t have to talk about anything.”

But talk they did, revealing a number of insights into the world they explored.

1. This project has been a decade in the making.

“I started going to these shelters about 10 years ago,” Mr. Gere said. “I had to have special permission to come in, I had to become a special inspector for the [Coalition For The Homeless]. Something happened along the way, the stars were aligned, we had a new administration in the mayor’s office. It opened up for us. We shot for one full night in ‘Bellevue.’ None of us could believe we actually got permission. No one’s ever shot there before. Ever. That was dead reality of what you’re seeing there—exactly the way it is in exactly the same place.”

2. Manhattan is an insane place, and the film reflects that.

“We were not trying to get the clean sound. We wanted it dirty. We wanted it to sound like New York,” Mr. Moverman said. “We wanted it to sound like the experience of being on a New York street corner where you hear so many things. Actually, if you want to experiment the next time you’re in the city, close your eyes on a street corner and listen to what’s going on. It’s actually overwhelming.”

3. The majority of the film was shot in long takes with long lenses inside restaurants and coffee shops, or even hidden on the streets, in just 21 days.

“You’re going to have to give up everything you’ve been accustomed to of how movies are cut, the rhythm of movies, and just sit back and allow this to wash over you a bit like a fever dream,” Mr. Gere explained. “The sense of time is exploded in this film. And it’s not an easy thing to do, to create that for an audience, that sets the rules of, ‘Okay, this is a different universe we’re going to be entering here.’”

4. The camera rolled as Mr. Gere was placed into live environments, waiting to see what would happen. With only two exceptions, no one recognized the Hollywood star—or even bothered trying.

“No one would make eye contact with me. Nobody,” Mr. Gere said. “I was in character and the visual of me was a guy panhandling. And something was coming off of me that was reading ‘panhandler.’ They could see that from two blocks away. Immediately, they were turning off that human aspect that wants to reach out, naturally. We all have that primitive instinct to connect. The longer this take went on, the more I could see how people were just turning that off. And it was deeply sad to me. At the same time, I was feeling guilty.

“The whole idea of shooting this film was based on the hope and prayer that we’d be able to pull this off. That I could be on the streets of New York and could have very long takes. That people wouldn’t recognize me or want to come up or engage me outside of the character. We really didn’t know if it was going to work.”

Mr. Gere glanced at Mr. Moverman. And they smiled, because in the end, it did.