It is not easy to keep track of what Andor Toro is doing as he flits between the hulking iron machines in his cluttered tool and die shop in a parking lot off Sag Harbor’s waterfront.

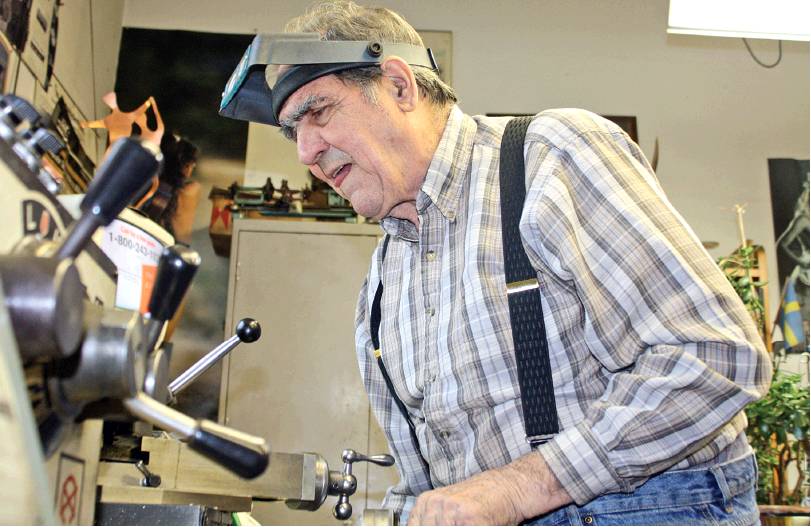

Rarely does Mr. Toro seem to settle into a project for more than a couple minutes at a time before he’s up and moving to the opposite end of the shop to dive into another task that he had apparently left as abruptly as the one he has just vacated. There is no conscious pause to assess where he’d left off, no quick review of plans to refresh his memory of measurementsjust an instantly intent hunch of focus, his thick brow furrowed as though he’d been immersed for hours, and a flurry of hands that manipulate a lathe or a press or a mill as instinctively as if they were scratching their owner’s head.

And so goes nearly every day in the life of the 82-year-old Hungarian native. Seven days a week he comes to his shop to tinker with one of the many projects he is working on for local artisans, friends and residents with fix-it issues too advanced for a simple part replacement.

Retirement is not really something Mr. Toro seems to see as an actual state of being. He retired decades ago, when the Bulova Watchcase Factory, where he worked for nearly 30 years, closed. When the factory closed, he bought some of the hulking machines, moved them into the former Grumman grinding shop up the street—where parts of the moon rovers from the Apollo missions were constructedand opened Toro’s Tool and Die. He eventually gave up the more attention-demanding tasks of making molds—handing that business off to a former Bulova colleague, Roger Reynolds, who now shares his shop—and turned to the fabricating and tinkering that now occupy his frenetic hands.

From the precise assemblage of a bronze-and-copper table for a Manhattan furniture designer to the milling of microscopic parts needed to fix an expensive Swiss watch, or modifying a gun sight, or fixing a pair of old steel hedge clippers that would elicit “They don’t make ’em like they used to” from anyone who held them, Mr. Toro is a Mr. Fix-it from a bygone age.

“I sharpened them up, toothey cut paper now,” he said with a broad smile, referring to the ancient hedge clippers, lunging them at a sheet of paper to show off his handiwork. Even as he described the process by which he had milled a new rivet for the clippers, his hands had moved on to the next task, grinding threads into an aluminum lamp stand—the clippers still rocking on the table where he placed them.

Mr. Toro moved to Canada from his native Hungary with his wife and her family when he was 26. A grocery bag stuffed into a cabinet in his shop contains a picture taken the day the family arrived on a steamship in Quebec Harbor. His wife died of cancer barely a year later, at 26 years old, just a month after giving birth to a daughter. A year later, he joined a crew of mostly Canadian and German toolmakers recruited by Bulova to work at the watch factory in Sag Harbor.

His daughter, grandchildren and five great-grandchildren now live in Calgary. Mr. Toro bought BMWs for two of his grandchildren as Christmas presents when they started college and gave his mint condition—probably much better than mint condition, in fact—1970 Corvette to a third. For years, he flew his own plane back to Canada for regular visits. Now he flies commercial, twice a year.

When he is in Sag Harbor, he is at his shop.

“This is his life,” his shopmate, Mr. Reynolds, said on a recent afternoon. “What else would he do? This is where he wants to be.”

As he fabricated a mold for battery cases used on military night-vision goggles, Mr. Reynolds watched with familiar amusement as Mr. Toro bounced midstream from one project to another, pausing briefly to point out a passage in a newspaper article about perceived disparaging comments that Senator John McCain had made about Long Island, one that mentioned the work done in Sag Harbor for lunar expeditions, in the very room in which he stood. Home for lunch and a stop at the waterfront to feed old bread and meats—sliced on the shop’s bandsaw—to the ducks and swans on Bay Street interrupt the day.

The shop walls still boast calendars from the 1980s, hung now well out of reach behind layers of rested tools, materials and sundry artifacts. The critical components of the machines on which the men work sparkle, however, with the sheen of fresh lubricants and meticulous maintenance.

Away from his “work,” the fragments of Mr. Toro’s leisurely interests hang on the walls of his shop along with the detritus of his duties. A fleet of antique and classic cars, meticulously restored by his own hands, down to the sewing of the upholstery for a 1919 Ford Model-T that he calls “my Lizzy,” occupy a hangar at East Hampton Airport, where he once stored his airplane and where, on occasion, he still assists plane mechanics with vexing repairs. A skeleton of a 1957 Thunderbird and another Model T slumber in a back room of the Bay Street tool shop, where components of their potential rebirth adorn the walls above them, awaiting Mr. Toro’s attention—which he seems to admit is unlikely to come.

Like retirement, conversation with Mr. Toro is vague and elusive, mostly a string of thoughts and stories about the quickly changing tasks at hand, or a story being told on a television in a distant corner of the shop. “Oh, he didn’t cut this,” Mr. Toro says as he passes an aluminum pipe laid on a band sawhe fires it up and zips the saw blade through the pipe. “There,” he mutters as he sets the two pieces down and heads across the room, picking up a mallet and tape measure for the intended task on his way. As Mr. Toro moves through the shop, he talks in a nearly unending sentence, pointing to tools and items and photos, each with a story of its origin, future or personality.

“Oh, my Jet Ski—I loved my Jet Ski,” he says picking up a randomly placed photograph of his one-time personal watercraft on a trailer in his driveway. “Yeah, I fool around with a lot of things.”