It was a night of ideas at the Sag Harbor Cinema this past Sunday with an architecture talk on a new building technology coupled with a screening of the 1936 film “Things to Come,” based on the H.G. Wells novel “The Shape of Things to Come.”

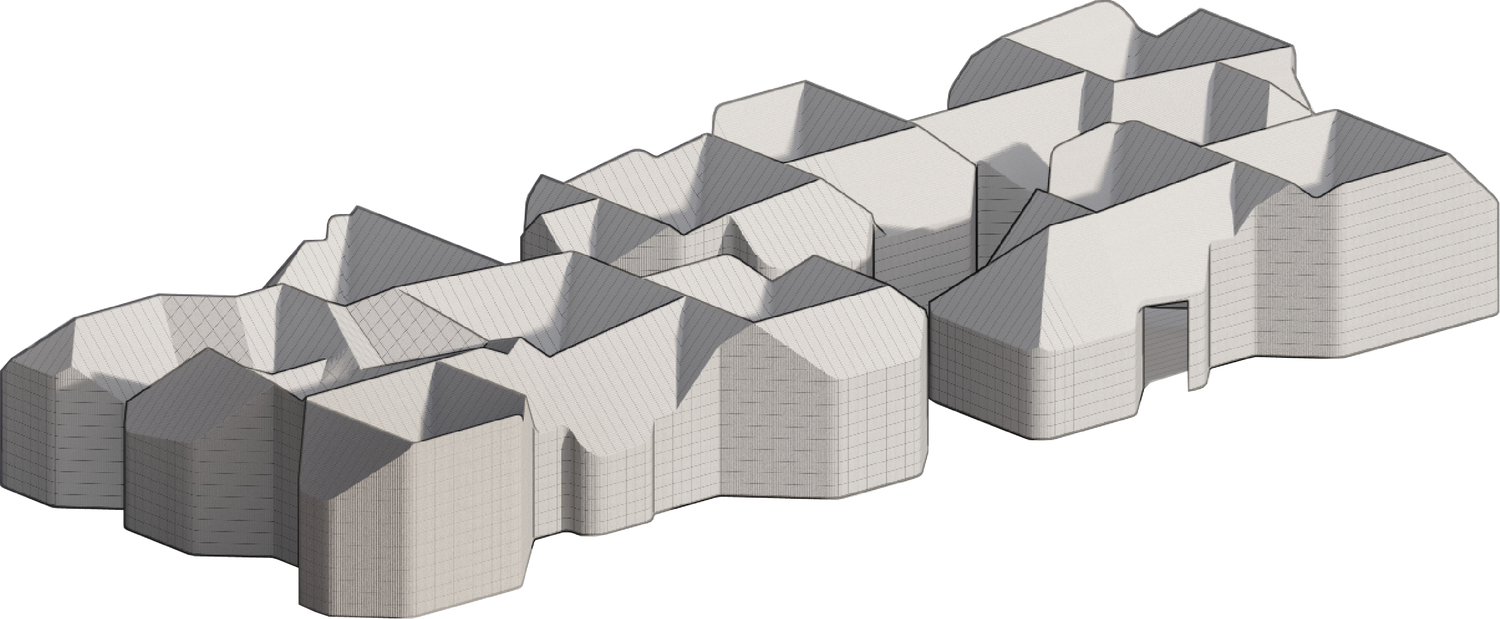

Architect Raffaella Bortoluzzi discussed her immersion into the world of the 3D printed home and its applications for affordable housing. Instead of printing on paper, 3D printing houses involves the use of semi-solid concrete essentially extruded from a printer, which is actually larger than the house. The printer — with legs, travel rails and an extrusion head — is driven by a computer to move in three directions. The concrete is installed in multiple layers, resembling layers of toothpaste, and the layout follows the computerized home design. Insulation is embedded in the concrete mix, and conduits for electrical work are also embedded in the pour. Organic matter can also be used for the printing.

Bortoluzzi designed a complex of affordable homes in El Paso, Texas, where furniture such as couches and tables are also printed in place. Doors and windows are integrated into the facades, and exterior walls become living walls on which to plant herbs. Rainwater is also captured at roof level through an integrated concrete receptor atop a hollow column exposed within the home.

Bortoluzzi claims that an affordable house can be built for $99,000 and takes just five to seven days to construct. Her project is a visionary approach to affordable housing. One wonders if people will tire of a layout carved in stone where they can’t bring in their own furniture? Of course the downside to adding a window later or even an addition would involve cutting out concrete or even part of an existing wall at quite an expense. These 3D structures have a height limitation of 54 feet. However, this method of construction may be well suited for big box stores like Home Depot or Costco. It will be interesting to see how this technology evolves in the future.

Things to Come, produced by Alexander Korda and directed by William Cameron Menzies, a well-known designer, is a fantastical story of war, destruction and the future of mankind. H.G. Wells wrote the screenplay for the film involving a plot spanning almost a century from 1940 to 2036. The black and white film, with its opening credits in angled block letters, its use of double exposures, and the composition of the imagery, is visually arresting.

The film begins in 1940 on Christmas Eve in Everytown, a small village in southern England. The village is busy with last-minute shoppers preparing for the holiday. There is talk of war at the home of businessman John Cabal (Raymond Massey) with his guests speculating over the future. Suddenly, an aerial attack occurs and the town is blown to pieces. A world war against an unnamed enemy, which would last for 30 years, has started and Cabal signs on as a Royal Air Force pilot.

By 1960, the entire world is in ruins. An illness called “wandering sickness” is related to aerial bombings, and the afflicted walk around in a zombie-like state until they die or are killed by the healthy survivors. This plague kills half the planet, and the world is in a post-apocalyptic state. The sickness ends by 1970, and a much older Cabal returns in an airplane. He talks of “Wings Over the World”, a new social order that considers independent states rogue nations. Everytown fights against this, but Wings uses supersized airplanes to drop sleeping gas on the town. No one dies and eventually everyone wakes up.

Cities are soon built underground to save the planet. Everytown is a white underground city. Cabal’s grandson Oswald (also played by Massey) becomes part of a new world order. So, in 2036 illness no longer exists and the horrors of prior existence have been put to rest. Space guns are used for space travel and Oswald permits his granddaughter to travel to the moon by space gun as an angry mob objects.

The film covers a world mired in a dystopian reality for nearly 100 years while the ending seeks a utopian solution for the future. It is strangely prescient given that World War ll began just three years after this film premiered. Wells’s idea that technological solutions could somehow save humanity is a bit hard to swallow. However, “Things to Come” challenges the motivations behind societal and political change. Wells’s imaginative storyline coupled with Menzies’s visual imagery make for a film that should not be ignored.

Anne Surchin is an East End architect and writer, vice chair of the Southold Historic Preservation Commission and co-author with Gary Lawrance of “Houses of the Hamptons 1880-1930.”