Tattered prayer flags wave in the wind over Rameshwar Das’s garden in the Barnes Landing section of East Hampton. It’s one of those damp spring mornings when the sun works hard to shine.

The 75-year-old sat on the porch while a downy woodpecker pecked at a shingle, the backyard and the woods beyond, in view. In Tibetan Buddhism culture, one that inspires Rameshwar Das’s spiritual leanings, the prayer flags offer protection.

“You leave them up until they fall apart,” he said. “The wind carries prayers.”

The writer and photographer who also serves as chairperson of the East Hampton Town Waterfront Advisory Committee is best known as co-author with his lifelong, similarly named friend Ram Dass of several books, including “Being Ram Dass.”

Dass, the author of 1971’s spiritual, meditation and yoga book “Be Here Now,” was not looking at the past when approached about penning an autobiography, Das noted in one of the many interviews he’s done since “Being Ram Dass” was published last year — 10 years after they began writing the book and two years after Dass’s death. When they submitted the manuscript, however, it was nearly 200,000 words.

It was 1968, when James Lytton, a young Wesleyian student, attended a lecture by Richard Alpert, the Harvard Professor who was famously fired from the Ivy League university while conducting experiments for the Harvard Psilocybin Project with Timothy Leary.

The talk was not at all what anyone expected from the former psychology professor, who had traded in his tweed suits and wingtips for a flowy white gown and bare feet, even in the frigid Connecticut winter.

Unknown to all who gathered in the student lounge, Alpert had just come back from India and was newly reborn as Ram Dass, a name given to him by his Hindu guru Neem Karoli Baba, also known as Maharajji or just plain Guru.

Ram Dass means servant of God and the talk could be considered the spiritual leader’s first sermon, lasting into the wee hours of the morning. By daybreak, Lytton — who would later change his name to Rameshwar Das — was infatuated enough to seek out “the old man in a blanket” at the foothills of the Himalayas himself.

Das lived in India for 18 months before getting a “Quit India” notice from the government. Having outstayed his welcome, he headed to Japan to meet his parents in the spring of 1972. “It was fortuitous,” he said. “Dad and I had a rough time throughout my teen and college years. He wanted me to go to law school, and I went to India.”

“The trip to Japan was very sweet,” he said. The following fall, his dad died suddenly of a heart attack when he was 25 years old.

He grew up in Westchester, the eldest of three children. His parents taught him patience and fortitude, he said, especially when they traveled as a family across the country, camping at the National Parks.

He spent much of his youth, however, right here, at his grandparents’ summer home. His grandfather helped to form the Barnes Landing Association, a cluster of cottages built on a hill near Gardiner’s Bay in 1952. Today it encompasses 250 property owners and 220 acres.

His grandparents bought the original summer house, built between 1900 to 1910, in 1949. It still retains its original locust post foundation, single pane windows and generous porch. Sometime later, a small kitchen and bedroom were added to the rambling ranch. A more modern addition of solar panels provides electricity to both houses on the five acre property.

Historically, the area was cut for firewood which was used to keep fires burning in home hearths and at local brick kilns. Coastal schooners shipped the oak and beech to New England and New York City.

“My grandparents planted for privacy,” he said, walking around the yard, thick with vegetation. Eventually more roads and more houses were built, blocking the water view, but you can still hear the waves hitting the beach below.

There was a path through the woods to the beach where he would fish with their neighbor, bayman Morris Bennett. “Summers were much more low key,” Das said. “The place I really loved.”

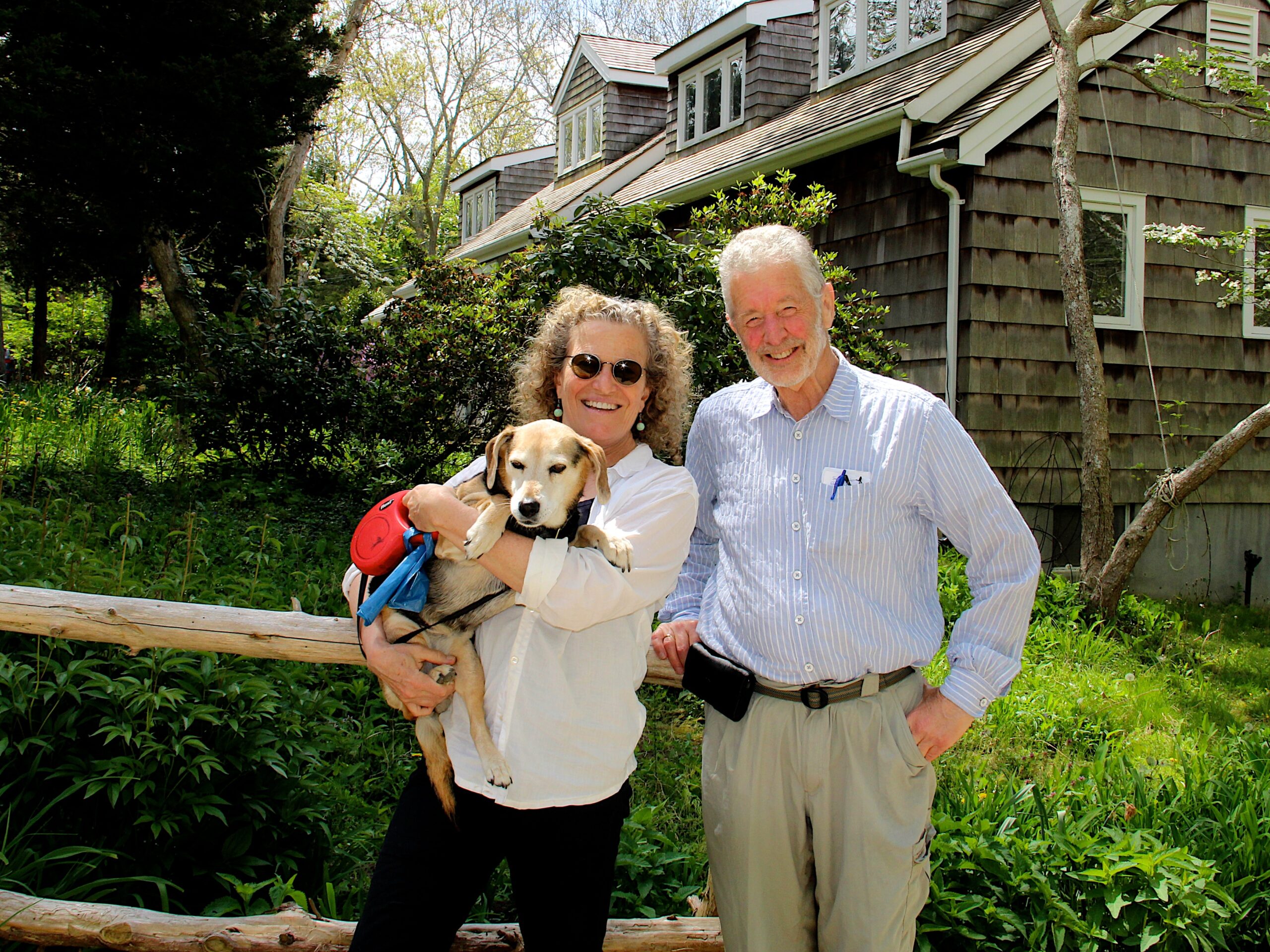

Das settled in Barnes Landing after his initial trip to India. He and his wife, yoga teacher Kate Rabinowitz, raised their two children, James and Anna Mirabai, in a second house, built in the mid 1960s. “We did a rehab when we had kids and put three bedrooms upstairs,” he said on a grassy path between the two houses.

He was working with Dass when he got the call that no parent ever wants to hear. With sirens in the background, he was told his daughter was hit by a car while riding her bike. She was a poet and a yogi, and at 14 years old, just about to graduate from the eighth grade when she was killed.

Her family is still dealing with the wreckage of her death nine years later. “It’s the worst thing that could happen,” he said. “Nobody can handle it.”

“She didn’t get to finish her life,” he said to Dass who looked him in the eye and replied, “Yes, she did.”

It was the moment Das saw death and life as more of a continuum. “It helped me do what I needed to do,” he said.

“The presence of death in my life changed me. I became more and more aware of the finite quality of my own existence,” he said. “Things can happen in a moment. There’s no control.”

Das leads a meditation group three times a week by Zoom. “I set myself up because then I have to do it,” he said. “It’s not called practice for nothing.”

Spiritual practice is a toolkit for dealing with what comes down the pike. “Stress and suffering are built into life,” he said. “You realize at some point, you need some way to work with that.”

His form of therapy is gardening. “I’m planting more flowers of late, annuals and perennials. I like things to volunteer and grow on their own.”

Lily of the valley dominates a hill, dogwoods line the driveway with purple vinca flowers underneath. Columbine, lilac, azaleas and a mint that tastes like orange are all in bloom. Heavenly Blue morning glories, peonies, shasta daisies and zinnias still to come.

Das takes photos of nature on his Barnes Landing Beach walks with Razzle, the family’s 14-year-old dog, they rescued from ARF. He uses Photoshop and turns them into psychedelic symbols of our times.

Das took a haunting portrait of his cohort that ended up as the cover of “Being Ram Dass.” At 88, 20 years after a debilitating stroke, the man who became one of the world’s most cherished spiritual teachers checked out December 2019. “He had impeccable timing,” Das said.

“It came down to two things with Ram Dass,” he said. “Awareness, or consciousness and love. Also, they’re not really separate. They’re sort of the underlying fabric of everything.”

Back at the prayer flags, thornless blackberries arch over the entryway to the garden where tomato towers are yet to be built. Tiny asparagus stalks poked through the still wet dirt. The sun warmed up so nicely, you could almost watch them grow.