In a largely futile effort to avoid watching the news, which seems to just get more and more depressing, I decided to channel-surf until I found something less likely to compel me to bang my head on the wall. Oh wait, I didn’t channel-surf. Like so many others, our household has switched to streaming, which means the simple joy of flipping channels has become an annoying challenge. Pick the platform, pick the category you want to browse, click on something and find out your membership doesn’t cover it, pick something else …

Anyway, I finally landed on “Bee Movie,” with Jerry Seinfeld voicing the lead character. It’s an oldie, but somehow I’d never seen it, and this seemed like the perfect time. A movie about bees! With Jerry Seinfeld! I was sure I had found exactly the tonic I needed to improve my state of mind.

No such luck. Seinfeld’s character is Barry B. Benson, a worker bee frustrated by the boring, unrewarding life he leads in the hive. Note I said “he.” That was my first clue that this movie was going to deepen my ennui rather than cure it.

Worker bees are not male. They are ALL female. Adding insult to error, Barry’s frustration comes from discovering that once he chooses a job, that will be his job for life. In truth, worker bees change their jobs every few days, moving up from cleaning crew to forager over their lifespan. In an act of rebellion, Barry decides to abandon honey-making and instead venture out with the pollen jocks, also male, but larger, stronger and clearly more macho than their hive-bound cohorts.

Hilarity ensues, or so I assume. I was too annoyed by the wrongness of the whole thing to continue watching, so I have no idea what happened after that. But this disappointing experience seemed a good opportunity to talk about drones, or male bees, and what they actually do.

First, a honeybee hive with 40,000 bees in it will likely have just a few hundred drones, and those only during mating season, roughly May through October in our area.

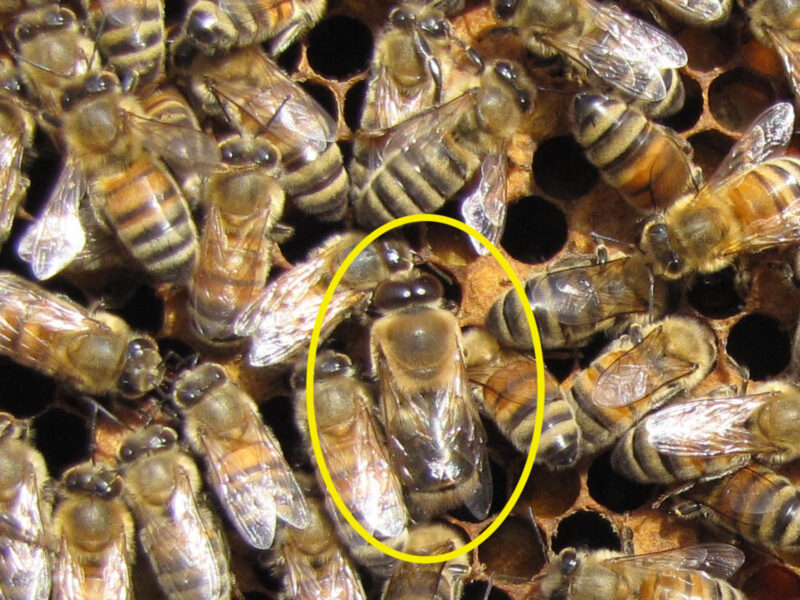

Although there aren’t many of them, they’re easy to spot in a crowd. A drone’s eyes are twice the size of a worker bee’s, and the drone itself is bigger and stockier than his sisters.

Now let’s talk about his “job.” The drone exists for one reason — to make more honeybees. After hatching in a custom-made drone cell, larger than those of his worker-bee sisters, he is scrupulously attended by those sisters, who feed him honey and muscle-building pollen, until he’s all grown up.

In late spring, his thoughts turn to romance, and he heads out of the hive looking for the girl of his dreams. His pheromones lead him to a drone congregation area, which will be within two miles of his hive. Here, with a few hundred to a few thousand other drones from the neighborhood, he will hover as high as 100 feet above the ground, waiting for a queen bee to come along so he can compete with those other drones for her attention. The queen, who has traveled three to five miles from her hive to avoid inbreeding with her own drones, is lovely, long and lean, elegant in stripes, a come-hither look in all five of her eyes.

Unfortunately for the drone, no matter what happens next, it won’t be a good day for him. If he gets lucky and is one of her chosen suitors, mating will be the last thing he does. A drone’s naughty bit, called the endophallus, explodes after intercourse. The rest of him falls to the ground, done and dusted.

After the queen has had her way with a dozen or so of her suitors she heads back home for some pampering from her minions. The rejected drone heads back to his own hive, where his sisters will feed him and perhaps reassure him that the chosen drones weren’t better-looking; the queen simply had poor taste.

Since drones don’t forage for food, take care of babies, or perform any useful domestic tasks, our drone will go back to relaxing, until the next sunny day finds him out cruising for love again. And so goes the drone’s life—which, at 90 days, is about twice as long as the average worker bee’s life. This is largely because the drone’s sisters work themselves to a state of tattered exhaustion in a mere six weeks. But free from all the honey-making, larvae-raising and so forth, drones can conserve their strength for mating. They are the original boy toys, despite what “Bee Movie” might have you believe.

It’s not a bad deal, until summer starts to wane. Once mating season is over and the drones are of no use to the hive, the ones who’ve made it this long are unceremoniously escorted out of the hive, where they are left to starve or freeze, whichever comes first.

It’s a sad sight, seeing the evicted drones huddled and shivering on the outside wall of the hive, wondering what they did to deserve this, while their sisters hunker down in a warm hive. But as with all things honeybee, the goal is to keep the hive alive, and sacrifices must be made.

More Posts from Lisa Daffy

More Posts from Lisa Daffy