Wintertime visits to architect Joseph Tarella’s new house were, at one time, very predictable.

The night would start with drinks and pleasantries, followed by the grand tour of his waterfront abode. Inevitably, when the group would wind up around a nearly 6-foot-long canvas, their jaws dropped.

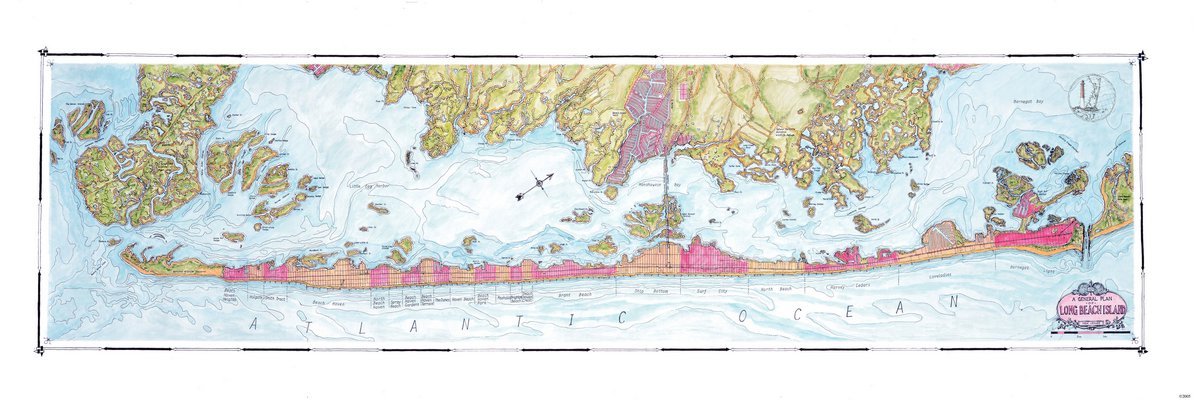

All at once, they digested the colorful map of precisely where they stood—Long Beach Island, New Jersey—as seen, interpreted and drawn by Mr. Tarella himself.

“Can I get a copy when you’re done?” would invariably break the stunned silence.

The first time it happened, Mr. Tarella was flattered. The second time, he was intrigued. The third, fourth and fifth times got him thinking.

What started out as an off-season project to cover a barren white wall in his new home has since morphed into a commercial venture called Coastal Art Maps. Over the last 13 years, Mr. Tarella has sold nearly 800 prints of Long Beach Island alone—the first of 21 total destination spots that also now include two East End maps. One depicts Riverhead to Shelter Island, the other Shelter Island to Montauk.

“Guys like maps. They like orienting themselves,” Mr. Tarella said last week during a telephone interview. “They’ll go into a gallery, go up to one of the maps and they’ll go to a particular place—where they think their house is or something they know well—and they’ll decide if it’s right or not. And if it’s right, they’ll almost always buy the map because it somehow connects them, which is nice. It’s exactly why I’d like someone to buy a map.”

Each maps starts with a location—often where land meets water, the avid swimmer explained. Then, Mr. Tarella gathers as much information as possible from tourist pamphlets and reference books before laying preexisting area maps over one another, seeing where conflicts or anomalies arise.

“Considering how exact the world is, there’s a surprising amount of inexactitude on maps,” he said. “Most maps are pretty good about the thing they’re mapping, but they’re not too worried about the things that aren’t their focus. You wouldn’t want to drive a car based on what you see on a nautical map.”

With a working list of inconsistencies, the architect sets out for a visit to “walk” the area, he said, investigating the clashes while picking up on local flavor and details, as well as getting his hands on regional maps. In fact, that is the first thing he does no matter where he goes.

“I think it is very grounding to represent your 3-D world in a 2-D format. It’s very empowering to see where you are in something you can hold in your hand, even knowing it represents a much more complex world,” he said. “If you see they have streets and mountains and seashore, that there are things you recognize, you feel like you might be able to navigate the place.”

Mr. Tarella stayed true to the East End's geography and decided against breaking up the North and South forks—as is done in many depictions, he said. It's not all about the South Shore, he said.

“I'm not sure whether people have agreed with me,” the 57-year-old laughed. “When they look at them, they still ask me, 'You drew this by hand?' As if there's another way. But people have kind of forgotten that stuff was drawn by hand up until a few years ago. You can't push a button and produce these maps somehow.”

The process starts with what Mr. Tarella calls a cartoon, or a loosely drawn, overall map that gives him a feel for what to emphasize. Once it's far enough along, he starts the final copy with a ballpoint pen on a large piece of vellum—first building up the roads, hills, lakes and ponds, followed by the towns, words and graphic measurements.

Color comes last, he said. Long Island is marked by reds, pinks, oranges and greens, surrounded by the swirling blues of the bays and sounds that empty into the Atlantic Ocean.

“The color selection is a slippery slope because people are very reactive to color,” Mr. Tarella said. “I can really push people's buttons.”

Or capture their attention. But with one particular map, the vibrant hues aren't what do it. It's the sharks.

For example, the Jersey Shore, 1916, representation is known as “The Summer of Blood.” Over the course of 12 days, five people from Beach Haven to Matawan were mauled by either one or a group of great white or bull sharks, a series of attacks that inspired Peter Benchley's 1974 novel, “Jaws,” and subsequent film of the same name, starring the late East Ender Roy Scheider.

The map details and commemorates the nearly 100-year-old event that once captured the world's attention, Mr. Tarella said.

“People are still befuddled by why this happened and why never again,” he said. “Year in and year out, the Shark Tour is the most popular tour Beach Haven has every summer. The idea that people want to go think about sharks before swimming in the ocean is beyond me.”

This past spring, Mr. Tarella unveiled two new maps—Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket Island in Massachusetts—and is now brainstorming new locations to draw during the cold winter months. Perhaps the Chesapeake Bay area, he mused, glancing out the window of his Manhattan-based firm, Sawicki Tarella Architecture + Design, at the falling snow.

“On days like today, it would be nice to be sitting at my table at home, drawing something,” he said. “The first map, Long Beach Island, is still my favorite. I had no idea where this was going to lead. I'm a believer of serendipity to a certain extent. You can't always plan your whole life and things happen, sometimes, that you're not expecting. And going for those is better than not going for it.”

He laughed, and continued, “I think that this first one has taken me on a pretty nice journey already. I didn't think it was going to be anything other than hanging in my living room.”

For more information, visit coastalartmaps.com.