Even in death, Truman Capote has been on a roll, especially in the Hamptons, where he lived for more than two decades.

The writer and bon vivant died in 1984, but in some ways it seems like he’s never truly left the cultural landscape. The most recent indication is the production of “Tru” at the Bay Street Theatre in Sag Harbor. Starring Darrell Hammond, the play received rave reviews when it opened the end of May.

The one-man play, which has its last East End performance this Sunday, is set in Mr. Capote’s apartment in Manhattan, but it could just as well have been set in Sagaponack. He bought a house there in 1963 with his partner, Jack Dunphy. It would not necessarily be recognized today because of extensive expansion and other changes, but what has remained consistent is that the property is just shy of 4 acres. The house on it was the first home the writer would own.

Of Mr. Capote’s Hamptons home, Gerald Clarke wrote in “Capote: A Biography” that “Truman at last bought a piece of American real estate, a small house in Sagaponack, just east of Bridgehampton. About a hundred yards from the ocean, the house had a high-ceilinged living room and a tiny bedroom downstairs; upstairs, reached by a spiral staircase, were two or three more rabbit-warren bedrooms. Jack hated the place immediately, believing, probably rightly, that they would both go mad in such a small space. He said nothing, but Truman undoubtedly read his face: not long after, he also bought the house next door. He would live in the first house. He said, and Jack would live in the second.”

The house was bequeathed to Mr. Dunphy at his partner’s death. When Mr. Dunphy died in 1992, the property was passed on to the Nature Conservancy. A year later, the artist Ross Bleckner bought the property for $800,000, and in the years since he has renovated and expanded the structures on it.

Mr. Bleckner enlarged the main house and added a 1,900-square-foot studio, a two-bedroom guest house, an outdoor pool and a garage. The main house is open and described as “mid-century modern with simple details.” There is an ocean view from one of the upstairs bedrooms.

In 2008, Mr. Bleckner put the property up for sale for $14.6 million. One description read: “The look of the property recalls the days when this area was more of an earthy retreat for artists and writers than for the wealthy and famous.” However, two brokers contacted by the Press informed that the house is now off the market. Those who are disappointed about this can still pony up the $18 million necessary to buy the building on Willow Street in Brooklyn where Mr. Capote lived in an apartment for 10 years.

This year is the 45th anniversary of arguably the two most important events in Mr. Capote’s life. When 1966 began, he was already a well-known and respected writer, perhaps as much so as such post-war male contemporaries as Norman Mailer, William Styron, John Updike, James Jones, Kurt Vonnegut and Irwin Shaw—the last three writers were East End neighbors.

By that time, Mr. Capote’s short stories had appeared in several of the best magazines in the United States, “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” had been a successful novel that was turned by Blake Edwards into a very successful film starring Audrey Hepburn, and Mr. Capote wrote the screenplay for “Beat the Devil,” a film directed by John Huston starring Humphrey Bogart.

But in 1966, the writer reached new heights of fame, which, in several ways, led to his downfall.

“In Cold Blood” was published by Random House that January. The book had appeared in four parts in The New Yorker beginning the previous September. The Clutter family in Kansas had been brutally murdered in rural Kansas in 1959. Mr. Capote read about the shocking event and decided to travel to the scene and write about it. He was accompanied by his close friend since childhood, Harper Lee, who would soon find literary and cinematic success with her one and only novel, “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

While in Kansas, Mr. Capote took thousands of pages of notes, interviewed the two killers after their capture and imprisonment, and worked on the book for six years. He spent some of that time writing at the Sagaponack house, the rest in Manhattan and Europe.

When “In Cold Blood” was published 45 years ago, it was an immediate sensation. It was hailed as the first “nonfiction novel” because the details of the case were distributed like clues in a detective novel. In praising it, Tom Wolfe wrote that “the book’s suspense is based largely on a totally new idea in detective stories: the promise of gory details, and the withholding of them until the end.”

Mr. Capote had figured out that since it was known who the killers were, the story’s climax had to be why and how they murdered the Clutter family. The book and its author would receive more acclaim when the film version, directed by Richard Brooks, was released in 1967.

Though he gave the impression of being more like an overly sensitive pussycat, Mr. Capote was lauded as a literary lion. Celebrities and New York high society were infatuated with him. And the feeling was mutual.

Socially, the author was also at the heights of his fame, when 45 years ago, he decided to throw what would later be called the “party of the century.” It took place at the Plaza Hotel in November, and the guests were the cream of the crop in arts and politics in mid-1960s America.

Many of those on the guest list were or would be connected to the Hamptons. They included Charles Addams, Edward Albee, Nelson Aldrich, Ben Bradlee, Jason Epstein, Ellliott Erwitt, Adolph Green, Thomas Guinzburg, John Knowles, Peter Matthiessen, Frank Perry, George Plimpton, Lee Radziwill, Larry Rivers, John Steinbeck and Andy Warhol. The party, which was in honor of Katharine Graham, publisher of The Washington Post, was called the “Black and White Ball” because Mr. Capote’s instruction was that guests wear one or the other.

The ball was a huge success, and Mr. Capote never quite recovered from it. The writer was swallowed up by the celebrity scene and his perceived place in it. He would never complete another book, though he tried.

Mr. Capote announced that his next project was a novel titled “Answered Prayers” and that he had already been writing it before being sidetracked by “In Cold Blood.” In New York, at the Sagaponack house and elsewhere, he worked on the novel, though not as much as he told people he did. He found writing the chapters about people in high society to be a slow, painful process, and one consequence was a sharp increase in his drinking. What made matters worse was that after excerpts were published in Esquire Magazine in the mid-1970s, many friends felt betrayed by the way he had portrayed them.

According to Mr. Clarke, “He had given up on “Answered Prayers,” but he was too proud to admit it, even to himself. One summer afternoon in 1983, over drinks in Bridgehampton, he came close to confessing his failure. ‘Writing this book is like climbing up to the top of a very high diving platform and seeing this little, tiny, postage-stamp-size pool below. To climb back down the ladder would be suicide. The only thing to do is dive in with style.”

In the first couple of months of the following year, 1984, Mr. Capote kept falling at his Sagaponack home and was repeatedly carted off to Southampton Hospital. On August 2, he was rushed to the same hospital because of an overdose of alcohol. Later that month he flew to the home of Joanne Carson, ex-wife of Johnny, in Los Angeles in the hope that this close friend would nurse him back to health. Instead, he died there, a little over a month shy of his 60th birthday.

Keeping the spirit of the writer alive, many books were written about him; with two more recent ones being “Tiny Terror: Why Truman Capote (Almost) Wrote Answered Prayers” and a reissue of Mr. Clarke’s massive biography.

A 2010 book, “Fifth Avenue, 5 A.M.,” about Mr. Capote and the making of the film “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” reached the New York Times best-seller list. In 2005 and 2006, not one but two movies about him were released—“Capote,” which won an Oscar for Philip Seymour Hoffman, and “Infamous.” The play “Tru,” written by Jay Presson Allen, is receiving new productions by theater companies all across the country.

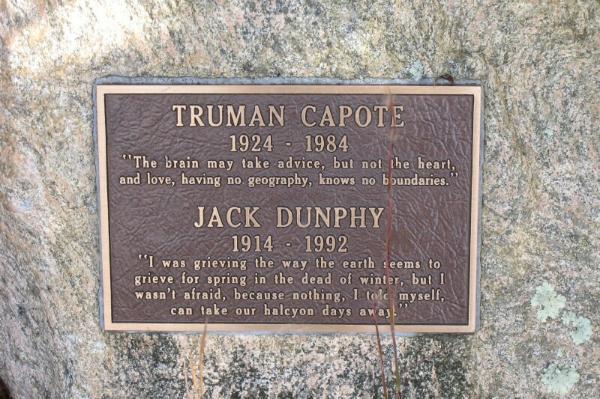

In a way, Mr. Capote hasn’t left the Hamptons and never will. When he died 27 years ago, his body was cremated, and Mr. Dunphy flew to Los Angeles to retrieve the ashes, which were then kept at the Sagaponack house. In 1994, friends brought them to Crooked Pond in the Long Pond Greenbelt. A peaceful place was created there for hikers and other visitors, marked by a plaque dedicated to Mr. Dunphy and Mr. Capote.