Nearly two decades after Lamont Smith’s passing, the famed horticulturist’s legacy continues to live on in an unlikely way: through the so-called “Shinnecock Tomato.”

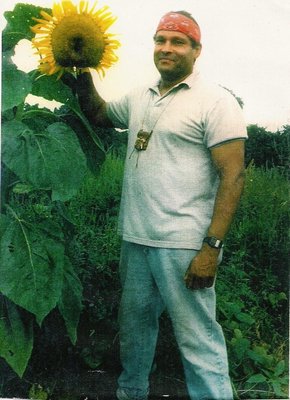

“He was really interested in learning the history of seeds and the stories of seeds and where they came,” recalls Aiyana Smith, Lamont’s niece. Ms. Smith remembers when she was a teenager Lamont would cross-breed sunflowers and tomato in his garden on the Shinnecock Indian Nation Reservation.

In addition to his work as a seed saver, Lamont, or “Monty” as most people called him, was a proponent of cultivating and gardening methods that worked closely with the earth.

“He would grow gourds. And what were the gourds used for? Pitchers and rattles. He did all those things, because he just kept digging deeper and deeper and deeper into the natural way of things,” said his brother, Gerrod Smith.

Although Monty was interested in researching traditional farming methods like using eel grass for vegetable beds, his relatives point out that his interest was more holistic than researching strictly Shinnecock Indian techniques.

“Western language likes to put things in a box and say, ‘this was Shinnecock way, this was colonial way, this was settler way, this was industrialized way,’ but we never really think about it like that,” Ms. Smith said. “We didn’t think about it as, ‘this is Shinnecock compared to something else’ … this is just a way of life.”

Mr. Smith believes part of Monty’s interest in horticulture stems from their childhood.

“Our dad was a farmer,” he noted. After their father, Charles Kellis Smith, tilled the land, Mr. Smith remembers walking along the field with Monty to look for grassnuts to eat. He said that in that simple way their life was connected to the soil.

Although Monty’s legacy is celebrated on the East End, when local seed saver Ken Ettlinger approached Ms. Smith about a variety of tomato that Monty had stewarded more than 20 years before, it came as a total surprise to the family. At the time, Ms. Smith was giving a presentation on recovery; this was especially coincidental.

“My uncle’s relationship to the land was really the story of his recovery. He had struggled with addiction and his brother, my father, took him up to the North Country, up to Canada, where they spent time out in the wilderness,” Ms. Smith said. “He really got a new appreciation of himself and his identity and the strength that he needed.”

Mr. Ettlinger first met Monty in the 1980s, through Dr. John Strong, who wrote, “We Are Still Here: The Algonquian Peoples of Long Island Today.” At the time, Monty was working to establish a garden on the Shinnecock Indian Nation territory using native plants, herbs and vegetables, while cultivating the earth using traditional methods. One of those methods—“the no-till”—is still referred to as “Monty’s way.”

“His garden was beautiful. He had a long row of circles along one edge planted with the three sisters and he had beds of purple amaranth, sunflowers, corn, squash and many other vegetables,” Mr. Ettlinger recalled. “With Monty, John Strong was investigating how seeds could be stored underground through the winter, and one spring I was present when they dug up a cache of various corns protected by deer hide. We realized why flint corn was favored by northern tribes since it survived the best under these storage conditions.”

After Monty had selected and bred the tomato, the variety somehow traveled to Dr. Jean Mundy, who donated it to the Seed Savers Exchange (SSE), a nonprofit organization that promotes seed stewardship and diversity by storing and cataloging heirloom varieties. It was labeled “the Shinnecock Tomato.” Dr. Mundy has since passed, but it is assumed that she named the tomato after where it was obtained.

For years, the seed was stored in the SSE bank but not planted until Stephanie Gaylor, a seed saver who co-owns Invincible Summer Farms in Southhold, requested it because of her interest in local vegetable varieties.

The Shinnecock Tomato had no description, except that it was donated by Dr. Mundy, Ms. Gaylor said. Although Ms. Gaylor didn’t know the story behind the seed, she picks up “anything I think is from here, even old cabbages from the turn of the century.”

Cultivating the Shinnecock Tomato for years, Ms. Gaylor stewarded the strain into a new decade. In addition to the more than 350 varieties of heirloom tomatoes that are grown at Invincible Summer Farms, she maintains a seed library of more than 2,400 tomato varieties. Known for its fine flavor, the Shinnecock Tomato has since developed a small following.

Describing seed stories as “like playing telephone,” Ms. Gaylor explained that Mr. Ettlinger was the only living link to this story. As surprising as the fact that this strain ended up back with the Smith family, the story of the tomato is equally circuitous.

The modern tomato “crossed the Atlantic twice to make it to North America,” Ms. Gaylor said, noting that the plant was originally from South America. A Spanish Jesuit priest brought it to Spain in the 1600s, where it then spread around Europe. Then, in the 1800s, it crossed the Atlantic again from Italy.

“Food travels and so do seeds,” Ms. Gaylor said. “They are meant to migrate and change. People are like seeds.”

Saying that he considers the Shinnecock Tomato, “an honor to Lamont,” Mr. Ettlinger said in an email that he is “quite certain that Lamont received the tomato from [the Native Seed Search] and carefully selected what he thought was the best of the tomatoes as all seed savers do and in the process, made it his own, adapted to Long Island and his own garden on the reservation.”

“What is it that he wants us to do? Because for some reason, [the tomato] came to us at this point in time,” said Ms. Smith, who works as the executive director of Blossom Sustainable Development. The organization, which was founded last year, is focused on helping communities live healthy sustainable lives with a focus on serving the earth. Founded by her father, cousin and herself, they feel that it is especially fortuitous that the tomato happened to come back to the family less than a year after they founded their nonprofit.

“It’s a full circle kind of thing,” said Mr. Smith, who describes the tomato’s path back to the Smith family as “wonderful.”

He continued, “all of this is stemming from a tomato. But you can see it is so much more than that. What does that really mean in the grand scheme of things? This tomato is linked to history.”

More Posts from Alexandra Talty

More Posts from Alexandra Talty