It’s peak bug time in the garden, and last summer seemed to be a perfect one for Japanese beetles. Unfortunately, that translates into this summer being a good year for increases in the populations of one of our original invasive insects, which is also the most widespread lawn pest in the country. Some areas and neighborhoods will see swarms of them while others may see the beetles on only a few roses or munching on the foliage of a Rose of Sharon, but no matter how many you have, you need to begin to control and monitor them now. If you don’t, I can virtually guarantee that next year your JB problems will expand exponentially. Like many of our insect problems, the JB is an invasive. It first appeared in New Jersey around 1917, and during the 20th century it managed to spread south to every state down to Florida, north up to Maine and west to the Mississippi River, and there it seemed to stop. For a while. Now the beetle is showing up in Canada and in at least two West Coast states. In Canada there’s a bit of a panic because the beetle has shown up in two areas in huge numbers at a time when two Canadian provinces have banned what we’d call “homeowner” insecticides.The damage that the JB can do can be pretty impressive, as it can feed on and in some cases kill plants in two different ways. When the beetles emerge from the ground in late June through mid-July they are very, very hungry. With their chewing mouth parts they feed not only on foliage but on flowers as well. Known to be voraciously attracted to roses, the adult beetles seem to be attracted to certain plants and flowers over others, but sometimes they can be indiscriminate. As noted, they adore roses, both the foliage and the flowers, but I’ve also seen them mass and feed on cherry foliage, mulberry trees and even on poison ivy.

But the fun doesn’t stop here. Once the beetles have gorged themselves with your favorite hybrid tea or floribunda, they attract a mate, do the deed and the female then drops to the ground or seeks out your best patch of lawn, where she lays her eggs. The eggs mature into grubs, and guess what those grubs just love to eat? The delicious roots of your thriving, lush lawn as it begins to brown in ever-growing circles of dead turf. But more on this later.

The beetles rise on plants as the day warms and tend to fall to the ground as dusk approaches, then in the morning, as the air warms, they migrate (while feeding) toward the top of the plant, tree or shrub once again. They also emerge in the morning as individuals, but as the day warms they tend to congregate in groups, doing the most amount of damage. They chew the plant tissue between the veins, giving the foliage a skeletonized appearance that few other insects create.

If disturbed or in need of a new feeding or breeding site, the beetles can fly up to 5 miles away, but flights of a mile or less are usually more common, and this is how the population grows and inundates neighborhoods, then communities, and then, when conditions are right, the infestations can cover several square miles and more. One thing that does stimulate long flights are the scents of sex or the pheromones that the female beetles are sending out and travel downwind. Unless of course you’ve set up a beetle trap in the wrong location and it’s YOU that is inadvertently drawing the sex-starved males to your property, as the lure in these traps is of course … you guessed it … a sex attractant.

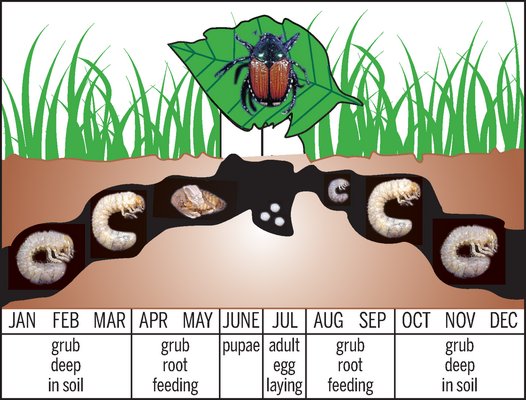

So this is how the grand scheme works, it’s called the life cycle, and if you follow and understand it you’ll save tons of money, cut your insecticide use dramatically and reduce or nearly eliminate your JB problems.

Let’s start just after the beetles have gone through their feeding frenzy on your roses, cherries, grapes, flowering crabs, hollyhocks or plums or maybe on your corn stalks or on the lythrum by the water’s edge. Once they’re nice and plump they start seeking a mate. Once they’ve mated in mid- to late July, the female seeks a patch of turf (or nice spot in your garden, but they do so love your lawn) and she drops down and lays her eggs … 50 to 80 of them. The eggs mature into tiny white grubs with dark heads, and the grubs seek out roots to feed on. As the group of grubs grow and need more roots to feed on, they travel in an outward circular motion, causing a brown area of lawn that will expand from the inside outward. Another telltale sign of grub damage is that the turf can literally be lifted from the soil and underneath you’ll find no roots, but probably many white grubs. Another thing to look for are crows stabbing at the turf in late August and September, as they love feeding on the plump grubs. Opossums and skunks also love to eat the grubs, and they will leave holes where they’ve been excavating so look for them.

If you suspect grub problems, one test that’s recommended is to lift the sod in an area of 1 square foot. If you find more than six grubs per square foot you need to take action. Lower rates generally don’t merit a panic, just caution and observation. Remember, though, that this test will work only in mid-spring and late summer, when the grubs are active near the surface.

The feeding on the roots continues until the soil begins to cool, and as it does the grubs migrate farther down into the soil, where they enter a dormant stage about 10 to 12 inches into the soil. As the soil warms in the spring, the dormancy is broken and the migration reverses as they again seek the freshly grown grass roots just below the turf. The feeding continues for several weeks, then stops as the grubs morph into the adults. The reason why it’s important to understand this life cycle is because at certain points the insect is particularly vulnerable to control … be it mechanical, chemical or organic. In the spring, when the grubs are moving up to begin feeding again, they are particularly susceptible to chemical controls (Dylox) for about two weeks. There is also a similar window in late summer.

Next week: control methods for the adult beetles. What works, what doesn’t and some control strategies. Keep growing.

More Posts from Andrew Messinger

More Posts from Andrew Messinger