Pulitzer-winning critic Paul Goldberger, who has penned books and countless columns on the architecture and the architects of New York City and the Hamptons, is out with a new book this month, “DUMBO: The Making of a New York Neighborhood,” which he says is more of a saga — with a lot of drama to it — than a conventional architecture book.

Mr. Goldberger has been the architecture critic for The New York Times, The New Yorker and Vanity Fair, and he’s documented the work of the East End’s influential modernist architects in 1986’s “The Houses of the Hamptons” and other books.

He also is a long-standing member of the Hamptons community, as is his new book’s central figure, David Walentas, the developer who transformed Dumbo from a fading industrial area into a thriving residential neighborhood.

Speaking from his home in Amagansett, Mr. Goldberger explained that the area known today as Dumbo has an unusual history all the way back to the Revolutionary War. But what most interested him is the more recent past; namely, Mr. Walentas’s decadeslong quest to redevelop the area.

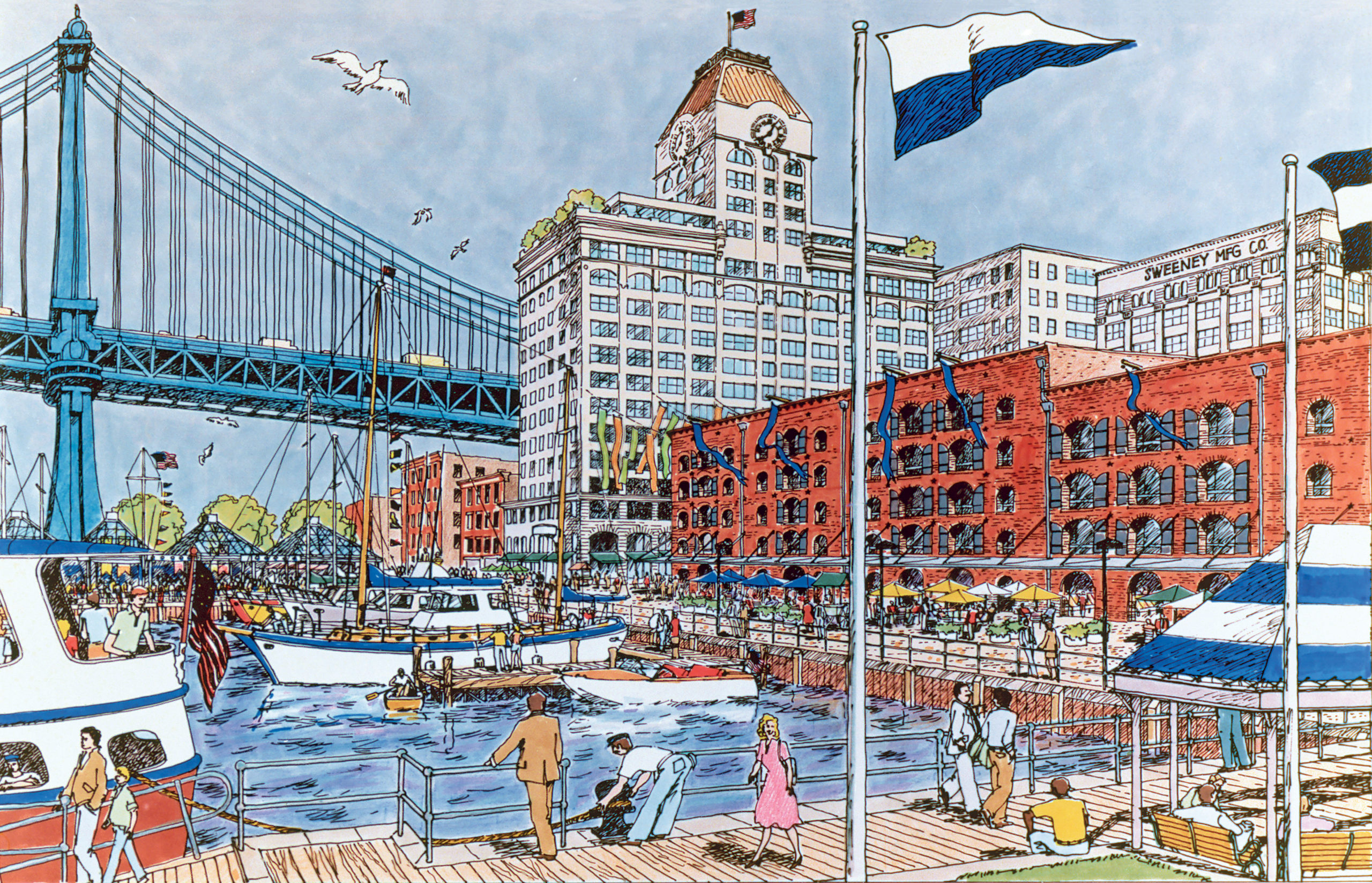

“He bought almost all of Dumbo in the late ’70s, when nobody was paying attention to it,” Mr. Goldberger said. “It was like this newly abandoned neighborhood, in this amazing place right next to the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges, and with these amazing views of the river and the Manhattan skyline.”

Mr. Walentas is known on the East End for his 115-acre Two Trees Farm, where the Bridgehampton Polo Club hosted public matches for two decades, ending in 2014. The property has since been subdivided, in another example of the billionaire’s real estate investment prowess and his vision.

In the case of Dumbo, Mr. Walentas saw potential where no one else did. He envisioned the next SoHo, with the added advantage of being on the riverfront. When he spent $12 million buying up what amounted to essentially the whole neighborhood — huge industrial buildings that were half empty and half warehouse space — people thought he was crazy, Mr. Goldberger said.

“The heart of the book is a story of his struggle over many decades to develop the neighborhood into something else,” he added. “And now it’s possibly the most expensive neighborhood in Brooklyn.”

In 2017, the penthouse in Dumbo’s most recognizable building, the Clock Tower at 1 Main Street, sold for $15 million — or $3 million more than Mr. Walentas had paid to buy the whole neighborhood.

Dumbo is a little neighborhood that started as a little settlement on the East River, but the history of those few blocks tracks the arc of American cities, Mr. Goldberger said.

“Most of the land was under the control of one family, of one guy, really, who in the Revolutionary War with a huge British sympathizer,” he said. “And he fled and abandoned it and went back to England. And when we won the Revolution and the United States was formed, the State of New York seized the land and sold it off.”

It became a village called Olympia, but that was driven out by industry as businesses ran out of room in Manhattan, he said, and in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Robert Gair, who pioneered foldable cardboard boxes, established the biggest box manufacturer in America there. “If only he lived to see Amazon and all that now,” Mr. Goldberger added.

But Gair’s heirs eventually moved the cardboard business elsewhere, and the large buildings became rental properties for smaller-scale manufacturing and warehouses.

“When Walentas discovered them, they were all owned by Harry Helmsley, who was a big New York developer who was happy to unload them,” Mr. Goldberger said, adding that he believes Mr. Helmsley thought Mr. Walentas was a sucker for taking the buildings off his hands.”

After Mr. Walentas purchased the properties in 1979, he could not immediately transform them into housing — the city’s zoning did not allow residential use. So, at the outset, he rented out the buildings as offices.

There was a reluctance, particularly among politicians, to admit that manufacturing was on the decline in the city, Mr. Goldberger said, adding, “You know how much politicians run on job creation.”

It took a while for lawmakers to realize that those old buildings were no longer suited to the needs of modern manufacturers, he said, but eventually they came around and realized the area had a much greater future as housing.

It was Mayor Rudy Giuliani who signed off on the zone change.

“That wasn’t until the 1990s, so [Walentas] had been there for 15, 20 years before it really hit its stride,” Mr. Goldberger said. “That’s when everything really clicked.”

“I’ve always been interested not just in, you know, single buildings by big-deal architects, but in the whole question of what makes a place,” Mr. Goldberger said. “What gives a place its qualities that are appealing? Or not appealing, as the case may be.”

These are questions he considers in Amagansett, East Hampton, Southampton and everywhere else, he said. “You want a mix of great older things that have been there a long time and give it a sense of anchor and time, but you also want a sense it’s a living place, and living places always evolve and change.

“... People may want to visit museums — they don’t want to live in a museum. You want to live in a living place. Yet if you fundamentally like the way it looks, you don’t want it to change radically either.”

That conflict — how do you manage change over time? — is explored in the book, he said.

He credited Mr. Walentas for not making Dumbo a museum or making it too perfect, like a theme park.

“Most real estate developers either don’t care at all about what things look like and only care about how much money they make, or they become obsessive about every last detail and don’t understand that sometimes letting something develop naturally actually gives it a more authentic feeling,” he said.

Being able to talk about that, and to watch somebody develop a whole neighborhood in an authentic way, was another reason Dumbo interested him, he said.

Though the zoning did not permit residential use, that did not stop some people. Before Mr. Walentas bought into the area, Dumbo was already a haven for artists living in lofts, Mr. Goldberger said. In fact, it was the artists who gave the neighborhood the name Dumbo, an acronym for “down under the Manhattan Bridge overpass.”

“They thought it sounded so ridiculous that it would keep the real estate developers away, because they didn’t really want to see the neighborhood developed and change,” Mr. Goldberger said.

He said Mr. Walentas realized that artists were the seed of SoHo and other successful neighborhoods, so he gave galleries and avant-garde theater companies favorable rental rates to give Dumbo a reputation as a cool place.

Mr. Walentas contributed the book’s foreword, in which he wrote, “In the end it was bigger and better than I ever imagined it could be, but there were years when I was referred to as the ‘Dumb’ in ‘Dumbo.’”

He recalled his business partners leaving and banks wanting nothing to do with him, and in the end what he thought would take five or six years took more than 30.

“And now, after all these years, the artists are still here, along with galleries, apartments, markets, restaurants, theaters, and startups, some of which have grown big,” he wrote.

“DUMBO: The Making of a New York Neighborhood” is published by Rizzoli and available now wherever books are sold. Powerhouse @ the Archway will host a virtual book launch with Paul Goldberger on Tuesday, May 11, at 7 p.m. RSVP at powerhousearena.com.