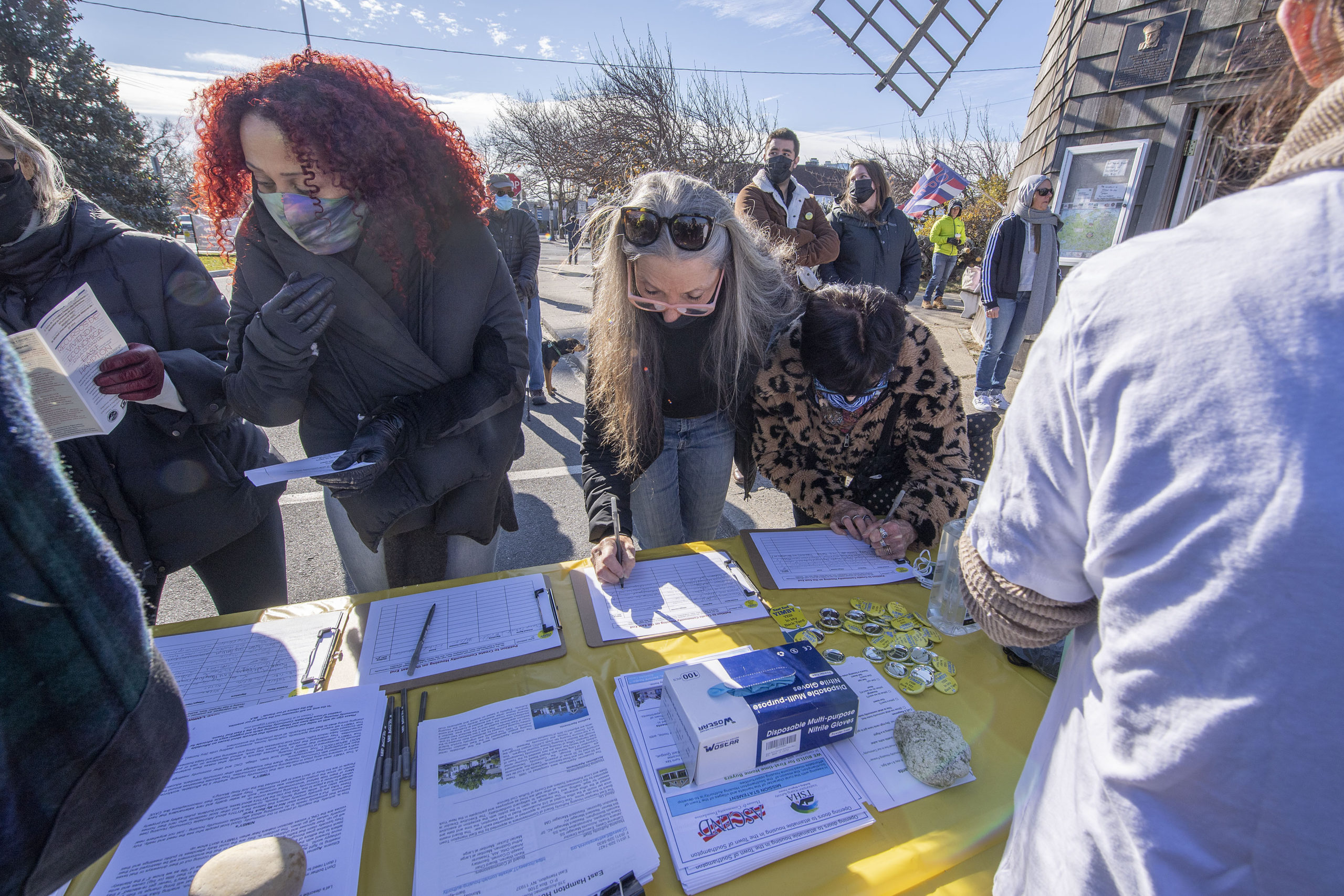

With the ongoing housing crisis seemingly getting worse by the week, about 100 people answered the call of East End YIMBY to rally at the foot of Long Wharf in Sag Harbor on Saturday morning. There, they demanded that something be done to provide more affordable housing for a growing segment of the population that is finding itself locked out of a future on the East End as house prices soar and rents follow closely behind.

In between spirited chants like “Housing is a human right, I will stay and I will fight!” the crowd heard a number of speakers, who both outlined the scope of the problem and offered hope that solutions might be forthcoming.

“I’ve been on the front lines watching this happen,” said Michael Daly, a real estate broker and leader of East End YIMBY, which stands for “Yes In My Backyard.” “Right before my eyes, I’m seeing friends, neighbors, young people, business people struggle to be able to afford homes, struggle to be able to find rentals.”

The coronavirus pandemic has only raised the situation to a “feverish pitch,” he said. “We’ve created a classic conflict between homeowners and renters. Renters are now second-class citizens.”

Daly outlined a four-step plan. First, “just take a breath and have some passion for our fellow man,” he said, an apparent reference to landlords who continue to raise rents. Second, he urged people to educate themselves about the obstacles to affordable housing. “A lot of it is ignorance,” he said, referring to homeowners who oppose affordable housing efforts in their neighborhoods. “I don’t say that with anger, I say that with disappointment.”

Finally, he said housing supporters need to support plans for affordable housing and continue to advocate for proposals that are put forward.

Sag Harbor Mayor Jim Larocca said he expected the Village Board to unveil a plan as early as next week or by January at the latest that would “define the entire village as an affordable housing district.”

What that means has yet to be defined, but Larocca said the village is obviously constrained by the lack of vacant land within its boundaries. “We’re going to have to be much more measured and focused” than the towns are, he said, adding that the village needs to find places for both workers and senior citizens to live.

“The sentiment expressed here is one we all share,” he added. “The problem is in the details.” He urged housing advocates to “come and be heard and be as specific as you can possibly be” when hearings on the housing plan are held.

Bonnie Cannon, the executive director of the Bridgehampton Child Care and Recreational Center, who is also chairwoman of the Southampton Housing Authority, also raised hopes that a short-term fix for some people may be on the horizon. After exhorting the crowd to support efforts to provide more affordable housing, she said, “We have a project, a very big project that can be done in Bridgehampton, that can have many affordable units in Bridgehampton. I will say no more.”

Curtis Highsmith, the executive director of the Southampton Housing Authority, also spoke. He told the crowd that while the housing authority had built more than 20 houses over the past five years, that was just a drop in the bucket. He said the town has several waiting lists with more than 1,000 names on them.

He also called for support when the housing authority brings forth new housing proposals.

“This has now become not just a community issue,” he said. “It has become a human rights issue.”

Erin O’Connor, a teacher who has lived on the East End since 2004 but now feels herself being pushed out by ever-rising rents, seemed to embody that.

“It’s easy for me to feel like a failure,” she said. “I’m a college grad with a professional degree, a career of which I’m proud. I did a lot of the right things, but I’m not financially stable.”

O’Connor recounted how she and her family initially lived in a home owned by her husband’s family in Bridgehampton, but after she was divorced, she had to move into several rentals, each more expensive than the last, forcing her to work longer and longer hours until she was virtually exhausted — and homeless, living with friends and commuting back and forth to Connecticut, where she has family.

It need not be that way, said Michelle Leo of Noyac, who said she was able to afford a house because of an inheritance.

“It shouldn’t take the death of grandparents and a random uncle to leave behind some funds so I can put a down payment on a house,” she said, adding that she didn’t want her children to live in an apartment in her basement because they could not find housing on their own.

And Minera Perez, the director of OLA of Eastern Long Island, an advocate for the Latino population, said that even people who have been forced to live in inhumane conditions are increasingly facing the threat of evictions as landlords seek to maximize their returns, and that OLA would help them in their legal battles.

Perez said too often affordable housing is viewed in a bad light. “We need to flip the script,” she said. “We are pitting affordable housing against other very important concerns like the environment, like water quality. Yes, we can have affordable housing and great water quality too.”