Iconic houses that are transformational are few and far between. For architects, a trip to Jefferson’s Monticello, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater or Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House is akin to a pilgrimage to Mecca.

After wanting to visit Philip Johnson’s renowned

Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut for more than 30 years, I recently embarked on a day trip with an old friend from architecture school. Despite looking at the famous view of the house in photographs, nothing, however, could have prepared me for the experience of visiting this historic estate—a place whose influence continues to both pervade and challenge our understanding of the American architectural landscape.

Philip Johnson donated the entire property, along with his art collection, to the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1986 but maintained a life tenancy at the Glass House. Both Johnson and his life partner, David Whitney, died in 2005 at the ages of 98 and 66 respectively.

The property opened to the public as a National Trust Historic Site in 2007.

Johnson, who said, “The Glass House is my 50-year diary,” bought his 5-acre property in 1946 and completed construction of the house in 1949. Over the next 50 years the property expanded to 47 acres, and Johnson continued to build what he called “events in the landscape:” a guest house, studio, follies, sculpture and painting galleries and reception center, all strategically placed, to create a series of dioramas set on meadows, fields and rolling hills.

The design for the Glass House started with the driveway.

In 1977, the installation of a gate—composed of massive pillars separated by a boom raised and lowered electronically—punctuates the arrival point at the property. A narrow road opens to a rounded forecourt/vestibule, not framed in stone but rather formed by aromatic, white pine trees carefully planted and now pruned to maintain the shape of this space.

From here, the approach to the house, as well as the other buildings, is purely processional. Johnson organizationally reshaped the landscape by adding dry-laid stone walls (in addition to those existing) and expanding the viewshed to encompass fields, meadows and remote forests. By planting and removing trees, the lines between the architecture and the larger canvas, the landscape, become entirely blurred.

The approach from the vestibule along a gently curving path, formed, in part, by the rounded, concrete Donald Judd sculpture (1971) finally opens onto a bucolic landscape and, in its midst, the Glass House sits jewel-like on a carpet of lawn.

To the right is the Brick House, a subordinate structure used primarily for guests. Bridging the space between the buildings and helping to form a courtyard is a round swimming pool added in 1955.

The Glass House itself is a 56-foot-long, 32-foot-wide, 10–foot-high rectangle. Charcoal-colored steel columns supporting a flat roof stand between expansive sheets of glass that project slightly on the outside from the otherwise flat wall plane. The house, a one-room space containing only a masonry cylinder housing a bathroom and a fireplace, was designed as a “pavilion for viewing nature.”

The activities of the house are defined by groupings of furniture: the kitchen island is adjacent to the living area, while the sleeping area is separated from the living space by a tall headboard. The painting, “The Burial of Phocion,” attributed to Nicolas Poussin, is freestanding and serves to denote the northern edge of the living area. The scene in the painting reflects a landscape remarkably similar to the view from the promontory, which is really an extension of the living area.

For Johnson, who brought modernism to the United States, having curated the 1932 Museum of Modern Art show, “Modern Architecture: International Exhibition,” the house articulates his particular, if not solipsistic, view of modernism. When it was first built, the house was considered to be revolutionary since there was no other building on the planet quite like it.

Johnson and Mr. Whitney held court here and invited architects, artists, writers and designers for an exchange of ideas, healthy debates and promotion of the arts. These salons often included both stimulating and tense interactions that added to the storied history of the house.

On one occasion Frank Lloyd Wright, who had something of a love/hate relationship with Johnson, came to visit. He walked in to a little cocktail party and started to recite the history of architecture. When he ran out of scotch, he walked across the room for a refill and moved the Elie Nadelman sculpture off center.

Upon refilling his own glass, Johnson moved the statue back.

Wright just exploded and said, “Philip, leave perfect symmetry to God!”

The statue to this day remains where Wright placed it.

The other buildings on the property collectively form the greater whole. From the promontory of the house, the view to the west includes a pond with the pavilion built at three-quarter scale. Behind it is the Lincoln Kirstein (a good friend of Johnson) Tower, looming large in contrast to the down-scaled structure in front of it.

To the north of the house a path leads to the Painting Gallery (1965), an underground building influenced by the Treasury of Atreus, a tomb in ancient Greece. This “kunstbunker,” as Johnson called it, contains wall-size rolling panels resembling poster racks on which to hang art. The space, with no natural light, does in fact feel tomblike.

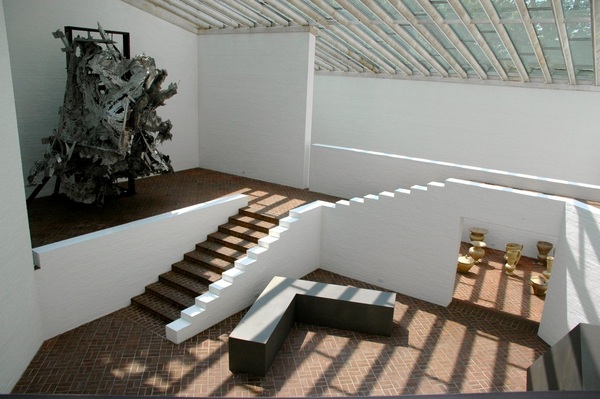

Further down the path is the Sculpture Gallery (1970), an open space divided into a series of vignettes. This arrangement of courtyards, plazas and stairs, influenced by Greek villages, sits under a sky-lit roof, casting shadows that continually change the nature of the space during the course of the day.

The last building completed on the property, Da Monsta (1995), was originally conceived as a visitor’s center. Called the “monster” on a visit by the late New York Times architecture critic Herbert Muschamp, Johnson quickly adopted the reference by dubbing it “Da Monsta.”

This structure, now used as a receiving area for visitors, takes Johnson’s oeuvre full circle. With complete abandonment of the orthogonal grid, there isn’t a right angle to be found in this gem of a pavilion.

Inspired by the work of Frank Stella, Frank Gehry and the organic creations of German expressionist Hermann Finsterlin, the building tilts, bends, curves and basically pushes its way out of the ground. Constructed from gunite sprayed over metal framework, the exterior is painted red and black in homage to rural regional vernacular structures.

Da Monsta is all about procession and the way people move through the space. As with all the buildings on the property, it has one window that frames the view of the next building beyond, in this case, Johnson’s Library Studio (1980), which in turn overlooks, through its only window, the Ghost House (1984) a chain-link house skeleton inspired by Frank Gehry. Here, the framing of views embellishes both landscape and buildings and symbolically connects the past to the present.

Johnson believed that knowing history is essential. Early modernism rejected everything that had come before and yet, within the Johnson’s own modernist canon, history became not only a source of inspiration but also a point of departure. The Glass House estate embodies 50 years of experimentation and representation and shows how our connection to history can be used as a tool for originality in the present.

More Posts from Anne Surchin

More Posts from Anne Surchin