Bob Nidzyn remembers a quiet man who lived on Basket Neck Lane in Remsenburg in the mid-1960s. The man used to walk the streets of the hamlet every morning to get his newspaper at a corner store on Montauk Highway, where Peppercorn’s Country Market stands now.

“We used to ride our bicycles and we’d see him on the street,” said Mr. Nidzyn, now 56 years old and the owner of Scales and Tails and Trackside Cafe in Speonk. “At first he seemed like a quiet, keep-to-himself kind of guy. Eventually he opened up and he’d say, ‘Hey, how you fellas doing?’”

The man was P.G. Wodehouse, an English-born comic writer who penned more than 70 novels and 200 short stories, and achieved international fame for characters such as Bertie Wooster and his valet, Jeeves.

“His use of the English language was absolutely masterful,” said Ken Clevenger, a retired lawyer who lives in Tennessee and is the chairman of the Wodehouse Society in the United States. “He would make language just physically alive. When you’re reading Wodehouse, you almost never stop and say, ‘Huh, what does that mean?’ It’s always so clear for you, and it’s rich language.”

Remsenburg, where Mr. Wodehouse lived for 20 years before his death and 1975 at the age of 93, has become something of a pilgrimage site for his fans all over the world, as well as for members of the Wodehouse Society, which has 19 chapters in the United States alone.

“His works are full of quiet rural, almost rustic country places, and in Remsenburg I think he may have found a little piece of America that was somewhat ‘English countryside-y’ in nature,” Mr. Clevenger said. “A lot of English country homes are near the coasts in England. And he wrote some, about 20 novels there and he died there and is buried there, so naturally it is a bit of a mecca for devoted fans.”

Back in April, Wodehouse fans came from as far away as Canada, England, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Italy and Japan to witness the unveiling of a marker commemorating Mr. Wodehouse at the Remsenburg Community Church, where Mr. Wodehouse is buried.

Mr. Wodehouse’s stories often found humor in the exploits of the upper-class in “Edwardian England,” said Andrea Jacobsen, a Wodehouse Society member from Pennsylvania who attended the dedication ceremony in Remsenburg.

“The humor was kind of based on the idea that aristocrats knew nothing and they were always depending on their servants to get them out of fixes,” she said.

The author, known affectionately by his fans as “Plum,” as he was known to his family and friends, took a winding route to Remsenburg. He was born in England in 1881, but lived in Le Touquet, France when the Nazis invaded, and was interned as a prisoner for a year until 1941. Upon his release, he made several broadcasts over German radio, which made him an unpopular figure back in England. Afterward, he found a new home in the United States.

After living in Manhattan, Mr. Wodehouse moved to Remsenburg to be close to his friend and collaborator, Guy Bolton, who also had a house here.

“The Hamptons are the Hamptons after all but for Wodehouse fans I think Remsenburg represents the ‘home’ Plum finally found after his unofficial but very real ‘exile’ from England as a consequence of the trouble he had over his ill-fated, and ill-thought-through, Berlin broadcasts in the summer of 1941,” Mr. Clevenger said.

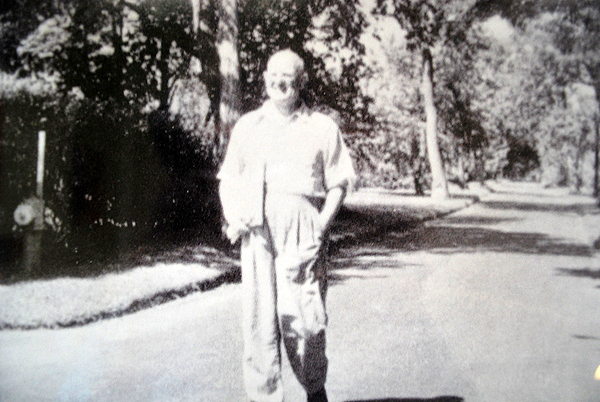

Mr. Clevenger said that, based on an account of Mr. Wodehouse’s life in Remsenburg that he cobbled together from biographies and conversations with relatives, the author was “a bit of a recluse” on the East End. He would wake up in the morning, do his “daily dozen” or “Swedish exercises” and make himself a breakfast of bread and tea. He would then spend most of his day writing with a pen and pad.

“His wife, Ethel, was a night owl,” he said. “She didn’t go out partying anymore, but she would stay up late, so she would sleep in. Late in the morning, after she had woken, he would go up and join her in her bedroom upstairs, and he would just visit and chat. They were very devoted to each other.” The couple is now buried side-by-side under the same headstone.

Mr. Wodehouse would often spend three or four hours per day walking, sometimes to the post office to pick up letters from fans and friends all over the world. He would often take a dog with him; he and his wife were animal lovers who often took in strays and were supporters of Bide-A-Wee in Westhampton.

Later on in the day, he might have had a “pretty stiff martini” with his wife, Mr. Clevenger said. “They had this beautiful little patio behind the house, and they would have sat out there late in the afternoon, visiting some more,” he said.

Before bed, they might have played cards, or watched baseball, or somewhat surprisingly, soap operas on television, he added.

“Soap opera is his bread and butter,” Mr. Clevenger said. “It’s an ongoing story, a saga, with characters who get into trouble and change and get out of it. I can understand why he would get entranced by any kind of storytelling.”

Mr. Nidzyn said that pilgrims from as far as Europe sometimes get off the train and step into the Trackside Cafe, looking for clues about their favorite author and where he is buried.

“They’d wander in and say, ‘Hey, have you ever heard of P.G. Wodehouse?’” he said. “And I’d say, ‘Heard of him?, Hell, I knew him!’”