Invasive organisms in our gardens and outdoor ecology have been plaguing us for eons and eons.

A few that come to mind quickly are the Japanese beetle, purple loosestrife, and the gypsy moth. More recently you may have read about the southern pine beetle, Asian longhorned beetle or possibly the emerald ash borer. But as a Manorville gardener discovered last summer there is an invasion of skin-blistering proportions and it may be on its way to your garden—or worse, it’s there already. It may be only a matter of time, a short time, until the giant hogweed, Heracleum mantegazzianum, invades our landscapes. It’s already being found in East Hampton and Bridgehampton. Worst of all, the Manorville gardener actually planted it because it’s attractive. Bad news though is that it can make you blind.

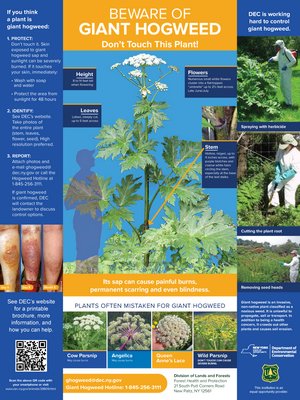

Giant hogweed is a large and showy plant native to the mountainous Caucasus region of Asia that lies between the Black and Caspian Seas. Introduced into Europe and North America early in the 20th century, it soon became prized for its bold, dramatic effect and was grown in many arboretums and private gardens here and abroad. In New York State, hogweed was cultivated in Highland Park in Rochester as early as 1917. It isn’t surprising that giant hogweed became a favorite specimen plant given the Victorians’ penchant for excessiveness. With its massive dimensions, often growing 15 feet tall and taller, and huge clusters of white flowers, hogweed has an imposing, almost ostentatious, appearance.

In both Europe and parts of North America, hogweed escaped from cultivation and naturalized along roadsides and stream banks. The plant spread so rampantly throughout England that, by 1970, it had become a prominent feature of the English landscape. More recently, giant hogweed has been found in the Canadian provinces of Ontario and British Columbia, in the states of Maine, Maryland, Pennsylvania and Washington, and has been reported growing in almost two dozen counties of central and western New York State as well as in our neighboring Nassau County and in nearby Connecticut.

Hogweed prefers a rich, damp soil, and in New York State, it is frequently seen growing along stream banks, in roadside ditches, and in moist waste areas. Increasingly, people report that from a single plant grown in their back yard for its ornamental value, an unmanageable patch of hogweed has developed over time. It is here, in the residential garden, in your backyard and woods, that giant hogweed is likely to pose the greatest health concern.

And just to complicate things a bit, this noxious weed has a striking similarity to a native noninvasive plant called cow parsnip and a garden ornamental known as Angelica. It can also have a striking resemblance to poison hemlock but in each of these cases there are simple differences that you can note that will allow you to know if you’ve got the real thing, a relative or an imposter.

The giant hogweed can grow as a biennial or a perennial herb growing from a forked or branched taproot like a carrot or Queen Anne’s lace, which are all in the same family. The easiest time to identify the plant is when it’s blooming but the best time is long before then. The flowers are small, white and numerous occurring in an umbel, again, similar to a Queen Anne’s lace or carrot flower—except in this case instead of the flat-topped flower cluster being a few inches across these clusters are up to 2.5 feet across. The stems are hollow, ridged, 2 to 4 inches in diameter, usually 8 to 14 feet tall with purple blotches and coarse white hairs, while the leaves are lobed and can be up to 5 feet across. Don’t touch it.

Seeds begin to germinate from early spring then throughout the growing season. The plant then grows foliage the first summer and dies to the ground. Then for each year for the next two to four years a leaf cluster develops from the overwintering roots until the plant bolts and flowers in early to mid-summer. After producing seeds in late summer the plants die leaving stems up to 14 feet standing through the winter. From fall through the winter the seeds are dispersed by the wind, birds and animals to places near and far where they germinate en masse the following spring.

It’s understandable why people wanted to plant this tall and majestic plant. Understandable from a distance that is. But get up close and rub against the plant, then add a little sweat or moisture and sunlight, and most people respond with a very severe skin reaction. The plant’s sap produces painful, burning blisters within 24 to 48 hours after contact, but in most cases moisture has to be present as well so in the summer the combination of the sap and perspiration does the unmagical trick. The technical term for this reaction is phytophotodermatitis. The plant juices can also cause painless red blotches that later develop into purplish or brownish scars that can persist for years.

If you suspect giant hogweed is on your property or if you think you spot it elsewhere you should call the Giant Hogweed Hotline at 1-845-256-3111 and describe where and what you saw so they can help make a confirmed sighting. If it’s on your property they will also discuss management options or offer help in eradicating the plant. You can also get an online brochure by following this link: tinyurl.com/ksy35d9.

Mowing, cutting and weed whacking are not recommended as a means of control as the plant’s large perennial root system will quickly send up new growth with a vengeance. Obviously, these tactics are also risky because they increase the opportunities for you to come into contact with the plant’s poisonous sap. If Roundup (glyphosate) is recommended as a control measure make sure you don’t get any of the product into freshwater wetlands as it can be fatal to a wide range of amphibians.

Giant hogweed seeds can be wind-blown several feet from the parent plant or may be carried by water to invade new areas. However, we are usually the ones responsible for spreading this noxious weed over long distances. Seeds or young plants from a friend’s garden, planted in new locations, help spread this weed quickly over distances much greater than the plant would spread naturally. The dried fruit clusters used in decorative arrangements and discarded outdoors can start a new patch in no time.

Just another thing to consider and keep your eyes out for in the garden this spring and summer along with the ticks, mosquitoes and poison ivy. I always want you to Keep Growing, just not Giant Hogweed.

More Posts from Andrew Messinger

More Posts from Andrew Messinger