We are surrounded by a graveyard. The waters off eastern Long Island and Block Island are littered with schooners, freighters, draggers, trawlers, tankers, barges, tugs, steamers, U-boats and other vessels totaling more than 1,500 spread across the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean and Long Island Sound.

The region’s wrecks date from the modern age, such as the Miss Caroline, a scalloper that sank with no loss of life south of Montauk in 2006, and the Johanna Lenore, a trawler that went down 40 miles off Southampton in 2011, with all hands saved, to the 18th century and earlier, including the most famous of them all, the Culloden.

A British ship of the line with 74 cannon that ran aground in a storm outside Fort Pond Bay in Montauk late in the American Revolution, also with no loss of life, the ship was salvaged and burned to the waterline by the British after they failed to refloat it.

Its remnants were rediscovered in 1971 in about 10 feet of water, 150 feet off what has been known for years as Culloden Point. They are now mostly buried under shifting sands on the bottom, but one of its recovered canons can be seen in the East Hampton Marine Museum in Amagansett.

Ben Roberts, 39, a former investment banker and trained electrical engineer whose passion since boyhood has been wreck diving, would no doubt love to identify and catalog every one of the wrecks out there.

Since 2018, through his company, Eastern Search & Survey, he has plotted about 500, including the Culloden, the Miss Caroline and the Johanna Lenore, with a unique, side-scan sonar system he designed especially for his boat, the Wahoowa, a 26-foot Glacier Bay twin outboard.

Side-scan sonar has been around for decades but Roberts’s system is lighter, more nimble, more stable, and easily controlled and operated by one man alone on his boat — and that makes for consistently sharp images.

A Virginia native who lived in Montauk and later Amagansett until this year, Roberts is well known among the wreck-diving community from Virginia to New England for the wreck details and imagery he posts on a Google map via the Eastern Search & Survey Facebook page. He and his wife this spring had identical twins, their first children, and moved back to Virginia to be close to her family’s home base.

Roberts has used GoFundMe drives to help pay some of his operating costs, but he and his dive friend Alex Barnard bought the sonar equipment together, and Roberts provides the boat and the days and weeks of time his labor of love demands.

Recreational wreck divers use Roberts’s imagery to get a bird’s-eye view — the big picture — of something that they otherwise can see only one detail at a time on a dive in the dark and murky waters of the Northeast. Fishermen use it because fish are drawn to wrecks, especially if there are surviving structures that rise from the bottom. Knowing where and how a wreck lies across the bottom tells them just where the fish are likely to be.

Roberts’s imagery and data also help commercial fishermen avoid wrecks with their nets, a common hazard that can ruin a dragger fisherman’s day and also damage the wreck sites themselves. Rogers has documented many a wreck that is covered in nets or broken up and scattered by dragger passes.

“I think what I’ve tried to do is unique,” Roberts said in an interview. “I’m into the mysteries of wreck diving and finding ships that are still missing. It’s all like a huge jigsaw puzzle, and I’ve tried to create a more collaborative community that shares information,” and thus speeds up the survey and identification process.

His survey work, which depends on clues and coordinates from divers and fishermen, as well as official records, has been a way to “try to get people to work together,” he said. “I spent 10 years as a local technical diver,” he said, before developing his one-man side-scan system and the information-sharing that supports it, “and it was so frustratingly slow” making any progress finding and identifying wrecks back then.

Roberts was among a team of divers that, in 2020, positively identified the wreck of the Adriatic, a famous casualty of a daring Confederate raid in Union waters by the steamship CSS Tallahassee late in the Civil War. A 181-foot, 990-ton three-master schooner, the Adriatic was the biggest of Tallahassee’s many prizes. It was set afire and went down in 220 feet of water about 30 miles south of Montauk after its 190 passengers and crew had been transferred to another captured vessel.

The general location of the event was on record, and fishermen had been snagging their nets on something in the area for more than 150 years, but at 220 feet, in cold, dark water, it had never been positively identified.

With Hampton Bays diver John Noonan at the helm of his boat, The Storm Petrel, out of Shinnecock Inlet, a team that did not yet include Roberts conducted a dive on September 22, 2016. Visibility was negligible, and the wreck was covered in nets snagged from draggers. It all seemed like a waste of time at first, according to an account by veteran Long Island journalist Bill Bleyer in Soundingsonline.com.

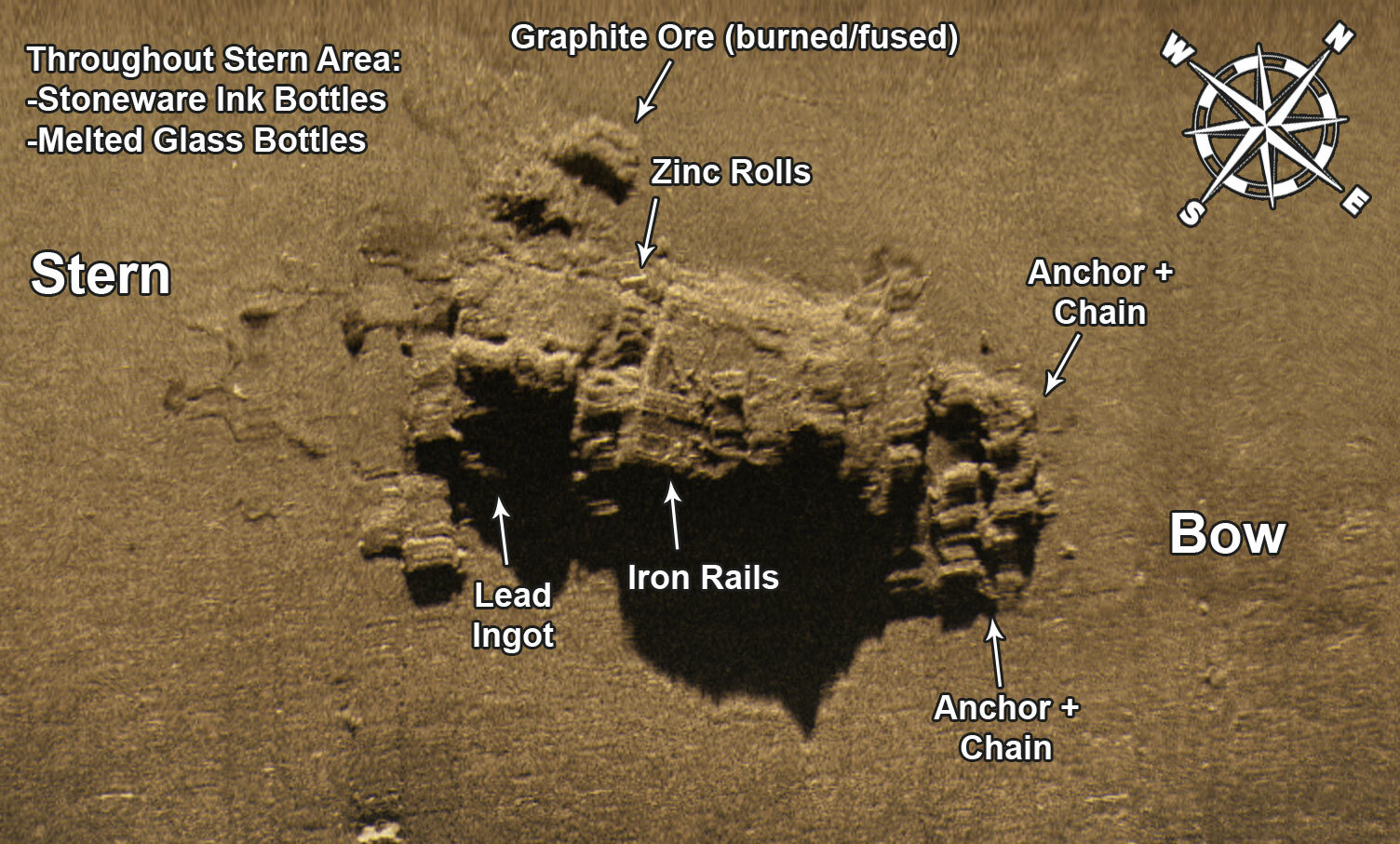

But patience is a virtue. The breakthrough came four years after their dive, when Roberts — who had joined the effort in 2018 and surveyed the site with his new system — found indemnity records in the National Archives that inventoried the cargo, including ink bottles from a particular London merchant they had identified in the wreck.

Newsday covered the discovery in a March 2020 article written by Bleyer, who also covered Roberts’s work surveying the wreckage of Long Island Sound’s greatest maritime disaster, the burning and sinking of Cornelius Vanderbilt’s twin-paddlewheel steamer, the Lexington.

The luxurious vessel caught fire in Long Island Sound en route from New York to New England on the night of January 13, 1840. After running eastbound in a blaze — out of control because the fire had burned through its rudder ropes — it finally sank off Port Jefferson, with the loss of all but four of its approximately 150 passengers and crew.

Visibility at the wreck site in mid-Sound is notoriously poor and sonar images taken over the years are fuzzy and reveal few details. Roberts’s survey in 2020 with his improved side-scan system revealed that the wreck, which was raised in chains in 1842 but lost again and broken up when the chains broke, “lies in at least three sections including the bow, the stern and a paddle wheel,” according to Roberts’s notes, which can be found by clicking on the wreck site symbol on his Facebook page map. “The largest and deepest section is the bow, which lies in soft mud that has been described as being like black mayonnaise,” he writes.

Go down the list of wrecks on the left-hand side of Roberts’s map and click on “SS Stockholm,” the Swedish passenger liner that infamously collided with the Italian passenger liner Andrea Doria in the fog in July 1956. The Stockholm site will be highlighted on the map about 50 miles southeast of Nantucket.

What’s down there 240 feet below the surface is the bow of the ship, which broke off in the collision. The Stockholm was able to take on passengers from the sinking Andrea Doria and limp into New York under its own power after the collision. Roberts notes that the vessel, as of 2021, remained in service as the MV Astoria.

Roberts offers a number of 2021 sonar images of the lonely relic, long suspected by fishermen to be the bow of the liner and positively identified by a dive group in 2020, lying just northwest of the Andrea Doria wreck site.

That wreck is known as the “Mount Everest” of sites for recreational divers because of its size and depth. In Roberts’s ghostly scans, the famous ship lies on its side where it came to rest on the bottom almost 66 years ago. Just click on “Andrea Doria” in his site list to take a look.

The wreck of one particular local tragedy from almost 40 years ago has not been confirmed, and Roberts is reluctant to press an investigation unless family survivors request it: His map shows a site and images of the possible wreck of the Wind Blown, a 65-foot steel-hulled long liner out of Montauk that foundered in a storm within sight of Montauk Point and sank on March 28, 1984.

Its story is the subject of the recent bestseller “The Lost Boys of Montauk,” by former East Hampton Star writer Amanda M. Fairbanks, a book that probes some personal histories and has generated resentment among surviving family and friends.

As Roberts reports in his note for the wreck, the site was initially reported as a “new hang” — a place where dragger nets were getting caught and torn — by local fishermen a week after the boat went down with its captain and four crew. The site was later misidentified as a sunken “yacht.” Roberts scanned it in 2018, 2019 and again in 2020 and reports that “the remains of a very broken-down and partially buried vessel with debris spanning approximately 65’ in length.” That’s the same length as the Wind Blown.

“Diver inspection pending,” he says simply of a rare wreck site, where there are still survivors of the people who died. Raw nerves and reverence, for the time being, may be keeping this site off limits.

Roberts’s remarkable work has been a glorified hobby for the past four or five years, but now it’s beginning to pay off. Taking on a partner company called Marine Imagining Technologies, Roberts’s company, Eastern Search & Survey, has been awarded government contracts to search for fallen airmen overseas.

The only detail he could disclose about their first mission — which will be on a boat to be chartered by his partners — is that it will take him to the Pacific. “But after July,” Roberts added, “I’m looking forward to scanning local wrecks” again.

He added, “I have multiple lifetimes worth of work to do.”