When Laini Farrare, a scholar from the University of Delaware’s Winterthur Program in American Material Culture, began working on her master’s thesis, she kept one important question at the forefront of her mind: What details can objects from the past tell us about those who used them?

It is, in many ways, the essential question for anyone interested in American material culture, which is the study of historical objects — furniture, silver, prints, paintings, textiles, historic books and ledgers, and more — for the specific purpose of understanding or uncovering the past.

For her thesis, Ferrare was specifically concerned with the contributions of Black and Indigenous labor in late 18th and early 19th century America, in Northeast coastal communities, and she had three primary areas of focus: two mahogany chairs owned by a wealthy East Hampton-based ship captain, constructed with wood sourced by enslaved people at his mahogany plantation in the Bay of Honduras; the 1795 Gardiner’s Island Windmill, which utilized the labor of enslaved, free, and indentured people of color, both constructed by Nathaniel Dominy V; and the life and work of Isaac Plato, a free Black boat operator and woodworker working and living in East Hampton and across the Long Island Sound.

That’s what brought Farrare, a lifelong Delaware native, to East Hampton on Saturday, May 11, as she presented her thesis, “Blowin’ in the Wind: The Hidden Hands of East Hampton,” in a lecture at the East Hampton Library.

The lecture was accompanied by a slideshow of photos and documents from the library’s Long Island Collection, and delved into the intricate labor landscape of East Hampton during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. She points out at the start of her thesis that East Hampton is “deeply connected to histories of enslaved, free, and indentured craftsmanship during the late Atlantic World (1790—1834).”

The legacy of windmill technology and the ability of high status white men like Dominy to construct them is tightly linked to Black and Indigenous labor, and that aspect of the story has largely not been told or represented. Dominy supervised the construction of the Gardiner’s Island windmill, but the contributions of those “hidden hands,” the Black and Indigenous laborers who did the actual work, was often overlooked.

Ferrare’s thesis and corresponding lecture at the East Hampton library was an attempt to tell those stories through the research she undertook over several months before her graduation.

There was also focus on the Hook Mill in East Hampton, which stands at North Main Street and Pantigo Road, and was built by Nathaniel Dominy V in 1806 and, Farrare pointed out, remains one of the most visible icons of East Hampton’s early American history. While the Dominy family of woodworkers became well known for their construction of windmills, a deeper dive into historical documents sheds light on the fact that, in 1804, Dominy brought a man named Shem and “two Montaukett boys” with him to source wood for the windmill, highlighting the fact that the windmills and many other important structures built in the village during that era were done with Black and Indigenous labor, often unpaid. That information came from an account written by one of Dominy’s grandchildren, and became a jumping off point for Farrare to explore more about the history of Black and Indigenous labor in the town.

Farrare said she’s always had an interest in coastal history, but originally pursued a political science major while she was an undergraduate student at the University of Delaware. She made a pivot, however, after taking a historic preservation class that was part of the political science major requirement that captured her interest and made her rethink what she wanted to study.

Getting involved at the Winterthur Museum in Delaware sealed the deal for Farrare. The museum is home to a collection of nearly 90,000 objects made or used in America since 1640, displayed in the sprawling 175-room estate that was once home to museum founder Henry Francis du Point. Winterthur also offers graduate programs in partnership with the University of Delaware and has an extensive research library. It is surrounded by 1,000 acres of protected meadows, woodlands, ponds and other waterways, including a 60-acre garden.

Ferrare was inspired to enroll in the graduate program in American material culture at Winterthur after working at the garden there, and she decided early on that she wanted to focus specifically on what life was like in the early American north for Black and Indigenous people.

“A lot of the time, slavery is talked about in a Southern context, in the American south,” she said. “But New York City, Boston and Providence had huge numbers of enslaved people and a high concentration of Indigenous people in the area.”

Ferrare decided to narrow her focus to the East End of Long Island, after finding out about The Plain Sight Project, a collaboration between Donnamarie Barnes and David Rattray. Created in 2016, the Plain Sight Project aims to identify enslaved people and free Blacks from the 1600s to the mid-19th century, and to locate and preserve burial grounds, habitations, and work sites on the East End.

She also knew there was a link between the Winterthur Museum and East Hampton, as the museum has many pieces that were part of the Dominy family of craftsmen, which hail from the area.

Ferrare got in touch with Andrea Meyer, a librarian and archivist at East Hampton Library who also serves as the head of the Long Island Collection. The Long Island Collection was a key contributor to much of Farrare’s thesis, and she said that Meyer invited her to present the thesis as a lecture after it was completed.

Ferrare’s goal in doing all the exhaustive research, combing through historical documents and trying to stitch together the pieces of history to give a more complete picture of what life was like for Black and Indigenous people in the area during that time is simple, even if the work itself is not.

“Something I really want people to recognize is that Black and Indigenous history is everywhere, and these people are always within the margins,” she said in an interview ahead of her trip to the area for the lecture in May. “We know so much about people like Paul Revere and George Washington, but what about the people who worked to enable those people to be in those places?”

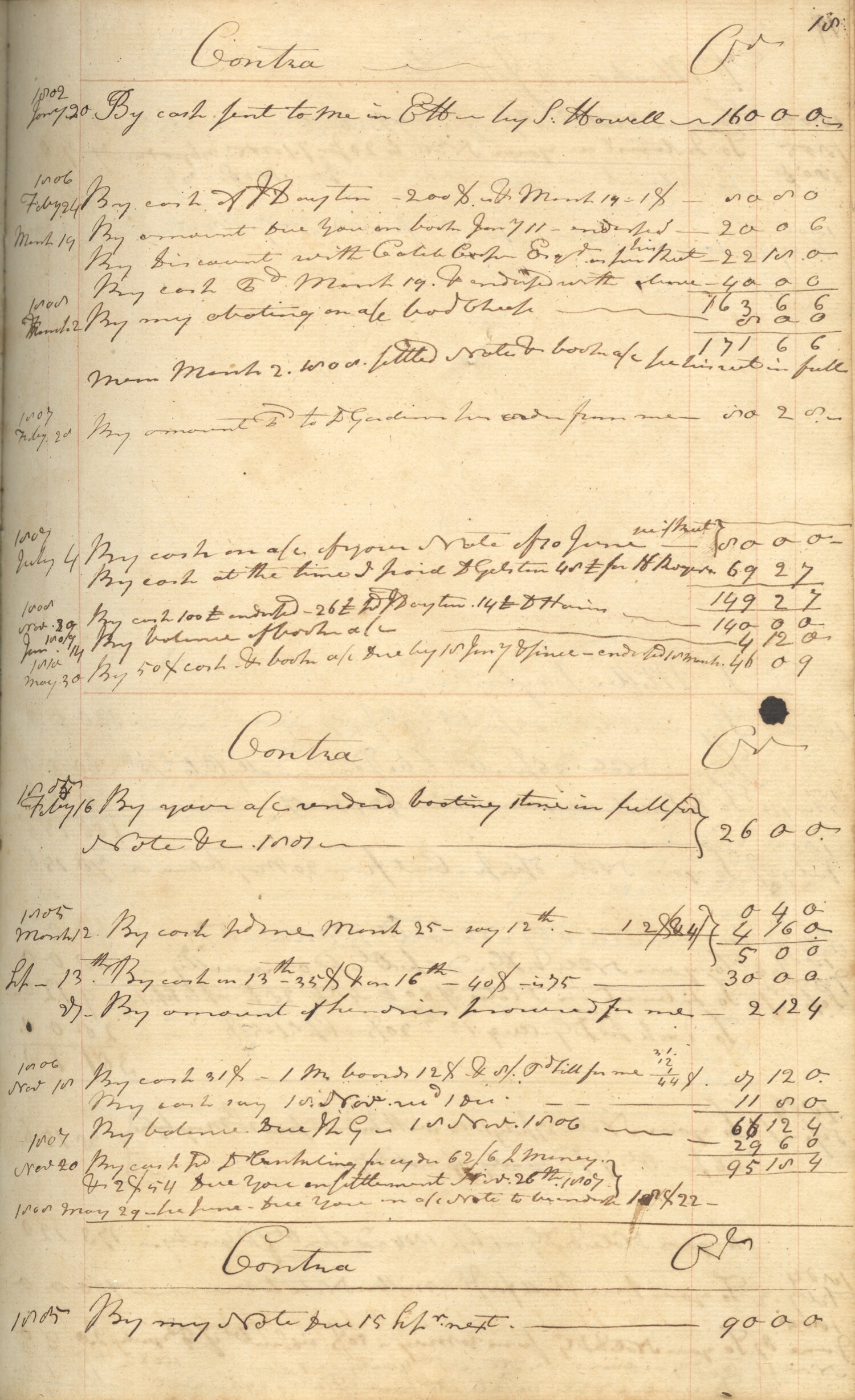

During the lecture, Ferrare shared photos of ledger and account books from the Long Island Collection that serve as proof and evidence of the ubiquitousness and importance of Black and Indigenous labor in early coastal American towns like East Hampton, and shine a light on how wealthy and powerful white men like Dominy and Gardiner interacted with them.

Dominy, who hailed from a family in which multiple generations were involved in woodworking and wood construction, built the large, white windmill for John Lion Gardiner. The original windmill, built in 1795, was destroyed by a hurricane in 1815 and later rebuilt.

Gardiner family documents that are part of the Long Island Collection include ledgers and log books that provide the kind of details that paint of picture of what life was like at that time. Gardiner’s records include phrases like “20 of my own,” referring to enslaved Blacks, as well as transactions with free Black men and also indentured Indigenous servants. Many of these come from a records kept in what Gardiner called “The Mulatto Book” or the “Book of Colours,” which outlined his work interactions with laborers, both free and enslaved, of color.

Farrare said the document was a big part of her research, and outlined in her thesis why it was so important, not just for seeing evidence of specific types of work done and whether or not those workers were paid, but also because it inadvertently revealed so much more about life at that time.

“These inventories are valuable documents that reveal more about family life and legacy,” she writes. “There are familial relationships with individuals having the same last name such as Martin and Isaac Plato, along with Isaac, Amos, Aaron, John and Caleb Cuff. It is plausible that many of these individuals shared kinship through parent/child, sibling, cousin, or aunt/uncle relationships, and that they worked together. Many of these individuals are enumerated in the 1800 United States Census indicating their freedom was obtained during or before 1800. The Cuff family, along with Sampson and Rufus, are listed as having large families and categorized as “non-white, free individuals,” leaving us to guess their racial identity.

She also points out that “a man named Plato (a different person than Isaac Plato) was in David Gardiner’s 1774 inventory, where he was indicated as being enslaved, and enumerated in the “20 of my own” documentation that Gardiner provides, yet in 1795 he appears to be paid and free.

“Stephen Pharoah and his indicated family are most likely Montauketts,” she continues. “As ‘Pharoah’ is a Montaukett legacy name in East Hampton. The Pharaohs were also paid for “bottoming 4 chairs.” This phrase refers to weaving reeds or rush for the seats of chairs, and there is emerging evidence that this was a skill of Montaukett women.”

What Farrare uncovered in her research about Isaac Plato, a free Black man who lived in East Hampton, was particularly compelling. A copy of a receipt from 1811 for payment to Plato for chestnut railings used to build the parsonage at the East Hampton Presbyterian Church revealed a lot about who Plato was, and what life was like for him, Farrare said. Documents show that Plato was also paid multiple times as a boat operator, transporting wood back and forth across the Long Island Sound between Connecticut and Long Island. He even transported the mill shaft for the Gardiner’s Island windmill from Connecticut to the island. As she points out in her thesis, other records of Plato’s work reveal that his labor contributed to the transportation of important commodities, such as textiles, food, livestock, windmill equipment, and furniture.

“Once I saw his name and him being paid for wood by the town for the parsonage, which is usually the home of the minister, I felt he was super important,” she said. “Isaac Plato’s life has taught me about freedom in early America, and the agency free Black business created in the area.”

Those receipts, which seem like simple and perhaps unremarkable documents, give a rare glimpse into the lived experience of a Black man during the building of a new nation, in a coastal environment. By examining structures like the windmills, and the chairs, as well as documents outlining work done by both free Black men by Plato as well as enslaved and indentured Black and Indigenous people, Farrare also raises important thought-provoking questions about the white men history credits as being fine craftsmen, and their relationship to the other men, which she outlines in her thesis.

“At what point does labor become craftsmanship?” the thesis asks. “At what point does craftsmanship become labor? What separates the two?”

Plato was born in 1767, although it’s unclear whether he was born in East Hampton or elsewhere, and whether his parents were enslaved. He was, however, born free and seemed to have carved out a place of significance and respect in the village through his work and what the documents back up was his presence as, essentially, a businessman. His work both as a boat operator, and his expertise in woodworking and sourcing the raw materials needed for woodworking were relied upon by wealthy white men like Dominy, and other important men in the town. He was paid $22.68 for 300 chestnut rails for the construction of the parsonage, an important job that wouldn’t have been left in the hands of someone without significant skill and respect in the village at that time.

It’s also worth noting, Ferrare pointed out, that Plato and many other Black and Indigenous men and women are noted in record books with traditionally English names, another example of how European settlers stole their agency and identity in an attempt at control and assimilation.

Even the fact that Plato signed his name on documents — an example of his literacy, which was rare for a Black man living in the country at that time — and was listed as a witness for certain transactions, tells a story about his life and status in East Hampton.

Ferrare’s research shows that the laborscape in East Hampton and other coastal towns at that time was complex — that free Black men worked and were paid for their work alongside enslaved Black men and women, as well as Indigenous people who had lived in peace and prosperity until European settlers showed up, and then suddenly were not only displaced from their land but became indentured servants in many instances. Ferrare’s research asks people to contemplate how Black labor histories contributed to the economic success of prominent coastal towns like East Hampton, and how what is conventionally understood to be the history of that time is, in fact, often incomplete.

Windmills were not cheap to build. Those that still stand, like the one on Gardiner’s Island, are “relics of prosperity,” Ferrare pointed out during her lecture, but those relics would never have existed without Black and Indigenous labor.