Eric Fischl was strolling through the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. “The Rijksmuseum is one of the largest, most important museums of culture in the world. The building is full of treasures,” he said. “I was there looking at art.”

The artist and co-founder of The Church museum in Sag Harbor was on a mission of inspiration, but between Vermeer’s “The Milkmaid” and Rembrandt’s self-portraits, he walked by a case of old woolen hats, called muts in Dutch.

“It just caught my eye,” he said of the row of cool caps. “I took photographs of them.”

When he returned home, he showed the photographs to Gretchen Comly, a knitwear and jewelry designer who recently moved from Sag Harbor to Springs. They discovered that the hats were worn by whalers in the 17th century.

The University of Groningen, 115 miles northeast of Amsterdam, was founded in 1614, around the start of the bowhead whale hunts in Spitsbergen, the largest island in the Svalbard archipelago, now a part of Norway.

A Dutch whaling station on Spitsbergen, as well as hundreds of whalers’ graves, were dug up by polar researcher Louwrens Hacquebord, Emeritus Professor of Arctic Studies, and his students at the university, during several archaeological digs from 1979 to 1981.

“The skeletons were still wearing their knitted woolen caps. Each cap was individualized; the men recognized one another only by the pattern of stripes on the caps,” one account noted. “The men were bundled up so tightly against the fierce cold that only their eyes were visible.”

Comly worked with the original hat measurements, available on the Rijksmuseum site, to create three different styles with slightly different shapes to be sold at The Church: Blue, Salt and Weir.

Comly started her knitting career on the film sets of Steven Spielberg. As the VP of business development, she often knitted during long breaks. “My creative outlet was a little business,” she said. “Then Kate Hudson started buying my stuff, and I decided to leave the corporate world.”

Gretchen Comly Handknits took off with the yoga set in Los Angeles, and she soon had a showroom in New York, with accounts across the country.

Although she’s more concerned with getting her two children off to school these days, she has a studio in her home where she creates jewelry and knitwear on a smaller scale, as Hamptons Handknits by Gretchen Comly.

Merino, alpaca and cashmere are sourced from Italy, Uruguay and India. It’s difficult, she said, to match the exact colors with today’s dyes, but she comes close, by using the time-proven methods employed in Milan. “I had to have everything done in Italy, because they have the most consistent dyes,” she said.

A more modern color palette of blues and grays were added to the earthier tones. The hats were worn out at sea, in the Arctic, arguably the coldest place on the planet, and then buried beneath the frozen earth for centuries.

Each style is made with or without small holes in the top layer, mimicking the wear and tear of the whalemen’s hats.

Like many of the originals, the hats are constructed using two layers, sometimes of different wools. Comly used cashmere to line many of her recreations, adding a touch of luxury that the whalers were not privy to. Still, their hats must have been a point of pride being that they were buried with them, like Egyptians buried with their gold.

Knitters in Montreal — “Individuals who work in their homes,” she said — make everything by hand without looms. It takes two weeks to complete the cap making process, with Comly overseeing quality control.

“They’re beautiful and interesting,” said Fischl, who designed the striking orange and blue labels. “Each pattern would identify the person. Maybe their wives made them. The style was general, but the color and pattern were specific to each whaler, just as their houses and boats were painted the same color.”

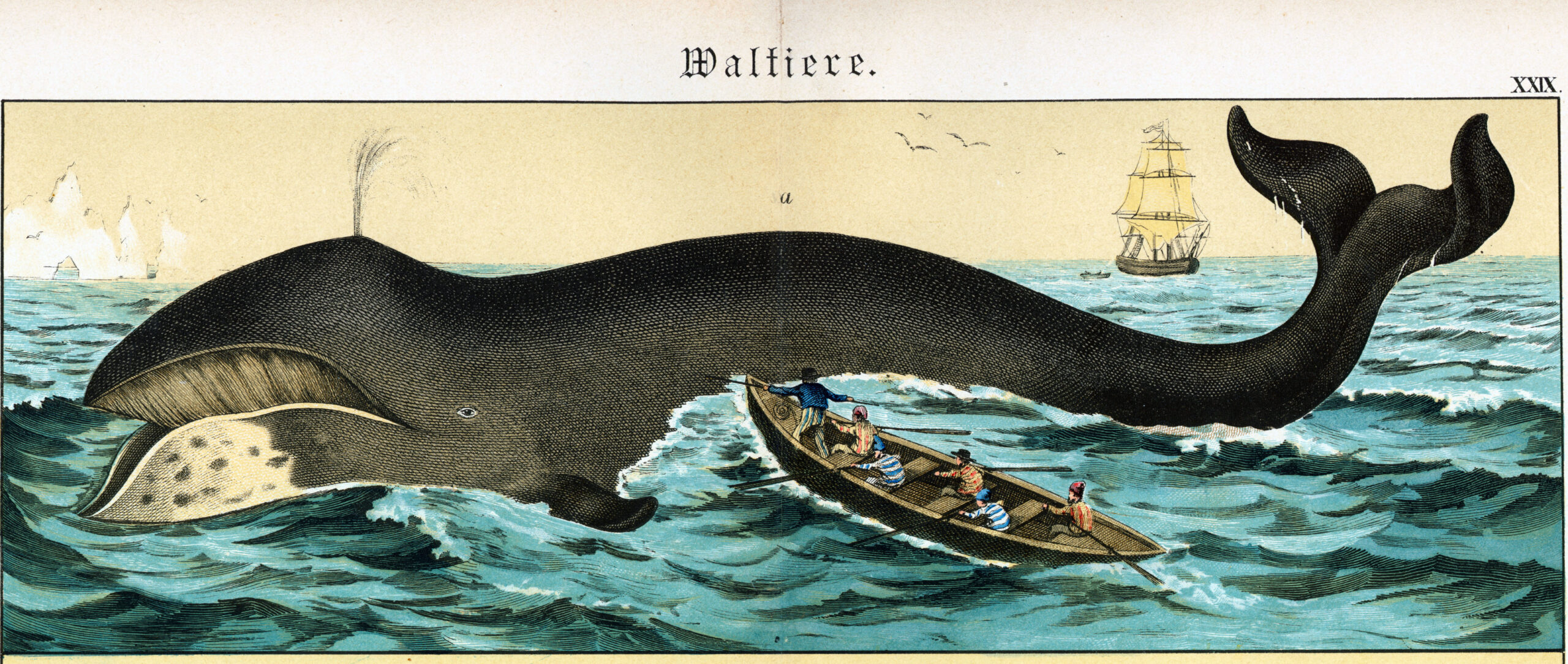

The Dutch and the English whalers began hunting the behemoths, which can weigh 100 tons and measure 60 feet in length, in 1611. The Dutch claimed that Captain Willem Barents discovered Spitsbergen in 1596 while exploring new routes to Asia. The English disputed that, declaring that Sir Hugh Willoughby had voyaged to the desolate island in 1553.

At first, the whaling expeditions were fraught with disaster. The Basques, who had been hunting whales around Greenland with great success, were enlisted to help. They learned that bowheads swim slowly and have predictable eating habits. Their huge black heads slice the surface of icy water, with their white lower jaw filtering plankton through baleen.

Bowhead whales, Balaena mysticetus, spend their long lives in the Arctic. The oldest bowhead is estimated to be about 211 years old, thanks to a sharp spearhead stuck in one’s 20-inch-thick blubber. More recent data, using DNA methylation, calculated their lifespan at 268 years. They also float when dead.

Hunters were able to spear them, aiming for the head, from small shallops, as the whales inquisitively maneuvered around floes in bays and harbors. Makeshift whaling stations were set up on Spitsbergen.

Flensing entailed beheading and hacking out the baleen, often referred to as bone but actually made of keratin. In addition to boiling the blubber, early whalers worked by rubbing sand to extract the oil once on shore. Young and old whales were taken. The remains went to waste.

By 1618, the Dutch had 24 ships around Spitsbergen. They attacked the English ships, killing whalers and burning down their station for encroachment in Horn Sound. They eventually agreed that the Dutch would stick to the northwest and the English to the south. Yet their rivalry over territories continued, until they killed most of the whales in pretty short order.

The Sag Harbor whaling industry began later. At its height in 1845, Sag Harbor had 64 whaling ships, according to a post on the Sag Harbor Whaling Museum’s Facebook page. The interesting post attempts to explain the lore of whaling, demonstrated by one of the most successful voyages ever.

On March 26, 1841, “the whaling ship Thomas Dickason, with Captain Wickham S. Havens in command, returned home after a voyage of 21 months and nine days,” with 4,000 barrels of oil, valued at $57,770 — about $731 million today.

Ultimately, the whales have paid the price for the lovely and quaint Village of Sag Harbor. If we are to pay homage to our history, we must pay homage to our ancestors of the deep. They are the ones who hold our future.