When voters in the five East End towns approved the creation of a special 2-percent tax on the sale of residential properties in 1998, with the revenue dedicated to purchasing farmland and wooded parcels for protection from development, its champions had predicted that the so-called Peconic Bay Community Preservation Fund would earn up to $15 million annually for the five towns over the 11 years for which it was initially approved.Proponents of the law, in the run-up to the 1998 referendum, were admittedly very conservative in their estimates of revenues from the tax—the projected $15 million was nearly eclipsed in the very first year. But it quickly became apparent that even their unspoken wildest dreams for the flow of income would be a drop in the proverbial bucket compared to what came flowing into preservation coffers over the next 16 years.

In January, one of the five towns’ CPF accounts most likely rang up the one billionth dollar to be garnered for community preservation on the East End through a real estate sale. Whether it was part of the nearly $3 million paid by Barry Rosenstein, on top of the record $147 million he laid out for an oceanfront East Hampton estate, or $1 of the $4,000 that the purchaser of a $450,000 summer home in a middle-class neighborhood would have contributed (first-time homebuyers are exempt, and the first $250,000 of a transaction is not taxed), is not yet known.

What is known is that the visionaries who molded the idea for the fund and battled for years to get it through a thicket of political red tape and special-interest opposition can laugh at the inconsequentiality.

“I don’t think anybody could have foreseen in the mid- to late 1990s the heights to which the East End real estate market, and especially that of the South Fork towns, was going to soar,” said State Assemblyman Fred W. Thiele Jr., the original author of the CPF legislation, who marshaled the bill into law with State Senator Kenneth P. LaValle. “Certainly, none of us thought it would ever bring

in more than $10 million or $15 million in a year. But nobody in 1997 could have guessed that someday an individual house was going to sell for $140 million … or where when someone sells a house for $40 million, people don’t even blink anymore.”

Driven by New York City’s dense concentrations of wealth, a fervor for opulence and a yearn by “1 percenters” to live within sight of the Atlantic Ocean, CPF income totals have bounded upward nearly every year of its existence, barely breaking stride for the Great Recession, and leaving those early paltry profit forecasts in the dust.

Through its 16-year life, thus far, the CPF saw only two years where its revenues declined from the previous year: following the bursting of the dot-com stock bubble in 2001, and in the depths of the Great Recession in 2009. In both instances, the accounts still brought in robust profits—$28 million and $40 million, respectively—and made big rebounds the following year.

In 2014, the fund took in a record-high $107.7 million and had its best month ever, with $14.4 million of revenues in the final month of the year, setting predictions of another mind-boggling high in 2015.

Southampton Town, with its long stretches of hyper-valuable oceanfront, has been the highliner for CPF income since the start, accounting for more than half of the total revenues. East Hampton has been a distant second, with a little more than a quarter of the total. In 2011, the two towns accounted for 90 percent of the $58.8 million the funds took in.

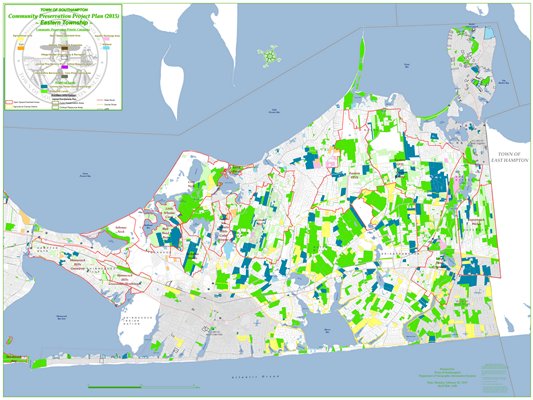

Along the way, the five towns have preserved more than 10,000 acres of land from development, protected more than 40 historic structures, and created some two dozen pocket parks.

In Southampton, the town has seen CPF revenues of $580 million through the end of 2014. Of that total, $507 million has been spent on 341 land purchases, totaling 3,814 acres. Of that acreage, 1,255 acres was farmland, 2,551 acres was woods, wetlands, parks and recreational facilities like Poxabogue Golf Course, the Conscience Point Marina and the former Summers and Neptune beach bars. The remaining 6-plus acres is land containing historic structures.

In East Hampton, where land preservation got its start on the East End, and where the idea of the CPF was born, the 2-percent tax has directed $250.5 million toward the purchase of 1,914 acres of land, most of it in broad swaths of woodlands.

“It really was an extraordinary gift that the people of the East End gave themselves,” said Kevin McDonald, a land preservation expert with The Nature Conservancy and one of the early proponents of the CPF. “It is working as it should. There were those who predicted mass calamity and the economy of the East End coming to an end, and that couldn’t be further from the truth of what has happened. It’s a great success story.”

Indeed, the CPF took more than a decade to wend its way to fruition. The idea for a real estate sales-driven fund that would help preserve the rural character of Eastern Long Island from suburban sprawl was conceived in the halls of East Hampton Town government offices in 1985. The town’s then-supervisor, Judith Hope, and a councilman, Randy Parsons, had both returned from vacations on Nantucket with tales of a land bank program just getting under way there.

“The Nantucket Land Bank had just gotten special legislation … and I thought it was a brilliant idea,” Ms. Hope said this week. “I said, this is exactly what we need in East Hampton.”

Ms. Hope and Mr. Parsons brought their vision for a real estate-funded land preservation effort to a young attorney who was representing the town’s Planning Board at the time: Fred Thiele.

“I drafted the original bill back then,” said Mr. Thiele, who would go on to serve as a councilman and supervisor in Southampton Town, and be elected to the State Assembly, before he would get to personally steer his bill to a referendum and into law nearly 15 years later. “We tried to get it passed in 1986 and 1987. Then the stock market crashed in 1987 and the recession hit, and from 1987 to 1992 nobody talked about it, because nobody wanted to put a tax on an industry that was in distress.”

In 1995, while community leaders were drafting an update to the Southampton Town Comprehensive Plan, the CPF program was rekindled.

“All of the communities were talking about protecting open space and creating hamlet parks,” Mr. McDonald, who was vice president of the Group for the South Fork at the time, recalled. “But there wasn’t the means to do it.”

With the towns of Southampton and East Hampton pushing them, Mr. Thiele and Mr. LaValle brought a bill creating a CPF for just the South Fork to the state and marshaled it to passage in 1997. It was promptly vetoed by Governor George Pataki, who bowed to pressure from construction and real estate industry lobbies. The state and local drivers of the program then redoubled their efforts and found new allies in the very industries that opposed the bill.

“We saw that if you wanted to keep the real estate market up and keep people coming out here, you had to keep the open space, to keep that rural feeling,” said Paul Brennan, a Bridgehampton native and real estate broker, who, at the time, was one of the local brokers who split from many in his industry, arguing that the CPF would help the East End real estate industry, not hurt it. “All you had to do is go up the island to what once was summer communities and see what they have become to understand the value of maintaining open space.”

Still, the bill that Mr. Thiele and Mr. LaValle brought back to the state in 1998, which now proposed a CPF for all five towns, was met with a concerted opposition effort by an upstate real estate industry lobby that directed $250,000 toward an ad campaign opposing it. But with a coalition that included East End builders and real estate brokers behind it, the bill again passed the legislature and was resoundingly approved by voters in a referendum.

It has since been extended twice by referendum, through 2030, with equally broad support from East End residents.

And yet, despite the many successes, most still look back at the fund’s vast power with a tinge of regret—that the whole program could have gotten off the ground a decade earlier; that the preservation managers could have gone after some precious lands in the early years that were ultimately lost to development; that restrictions on spending still frustrate preservation efforts’ ability to compete with the marketplace; or that some of the protections that the CPF thought it was buying have not lived up to expectations.

Most of the bill’s early champions point out that while the revenue totals are breathtaking, they are a product of a market like a freight train, that has only allowed the preservation funds to barely keep pace with development pressure. The funds, they note, continue to lose out to private buyers on parcels given top priority for preservation, due to restrictions on municipal purchases and the astronomical value of land to developers with grand plans. Despite being ready to write checks of upward of $10 million in some instances, the towns’ preservation efforts have been rebuffed by sellers on numerous occasions.

“We can make substantial offers, but they’re based on assessed value, not on market values that others are willing to pay,” Southampton Town Supervisor Anna Throne-Holst said. “I tell the folks who say you have to preserve this: Just because we have all this money doesn’t mean we can buy everything we want. We have to follow the letter of the law.”

The other great frustration of land preservation, both by the CPF and through other efforts, has been the failure of the purchase of development rights to halt development of lands thought to be protected open space.

After a 1990s court ruling declared that equestrian uses must legally be considered “agriculture,” hundreds of acres of land thought preserved from development disappeared beneath white fences and sprawling horse barns.

One Water Mill parcel, now owned by “Today” show anchor Matt Lauer, has had more than 60,000 square feet of buildings—including a three-bedroom house and plush clubhouse lounge—despite having had its development rights purchased for $3.5 million in CPF money.

Other lands have been made, essentially, expansive lawns, planted with sod and hidden behind towering hedges.

“What we have learned, not only about the CPF but all of our conservation programs, is that there are things we didn’t anticipate,” said John v.H. Halsey, president of the Southampton-based Peconic Land Trust. “We have protected a tremendous amount of farmland from development, and when we did so, we assumed that were protecting it for farming. Certainly, on the South Fork, that goal has not been realized.”

The CPF has earned $1 billion in 16 years. The 2-percent transfer tax has already been authorized to continue for another 16, through 2030. Most say another $1 billion in that time frame is quite possible, even with inevitable market downturns, if not a forgone conclusion. The towns, meanwhile, have more than $100 million on hand, from past revenues.

So, where will the money go?

At the time of its creation, some lofty goals were set for the use of the money—goals that would seem absurd if the forecasts for income had been even remotely accurate.

In Southampton alone, the town had created an initial wish list of 739 farmland parcels, making up 3,592 acres; 4,562 acres of other open space; 300 wetland parcels; and more than 200 parcels within the town’s village and hamlet centers. Shifting priorities make it hard to say how many of those targeted parcels in the town have still not been preserved or have been developed.

On the North Fork, broad swaths of farmland remain unprotected, and as land values there creep up, preservationists say that the CPF will be increasingly important to stave off development. But on the South Fork, the options for protecting big chunks of land are steadily diminishing, amid both the program’s successes and its failures. So CPF committees are looking down different paths to spread the reach of preservation.

In East Hampton, where most of the large undeveloped properties have been preserved, much of the new efforts have been directed at historic preservation and renovation. Mr. Thiele said he expects to see other towns directing more funding toward historic work in the coming years as well.

Wetlands protection will also be a direction of more aggressive land acquisition as concerns about water quality and rising sea levels grow. Last year, Southampton Town approved the use of CPF funds for the purchase of waterfront lots that can help dampen the impacts of severe storms by expanding wetlands. The town has made almost a dozen purchases under the new guidelines already.

Mr. Thiele said it is possible as sea levels continue to rise in coming decades that CPF funding could help towns lead a retreat from the coastline.

In Southampton Town, a first step was taken last year toward mending the failure of development rights purchases to preserve traditional agriculture. With the guidance of the Peconic Land Trust, the town modified its traditional development rights purchasing protocol to more specifically restrict the future use of two Water Mill properties, ensuring that the land will remain in food-production agriculture.

Farming industry advocates, led by the Peconic Land Trust, say they will press the towns to direct CPF funds toward the purchase of additional rights of lands previously preserved, to ensure they are not lost to equestrian or other non-farming uses.

“If the goal is to preserve farming, we need to do more than we have in the past,” Mr. Halsey said. “In that sense, as there are new realities that present themselves … the Community Preservation Fund can assist in addressing them.”

Mr. Thiele recently introduced the idea that a future CPF reauthorization, extending the program through 2050, could direct some of its revenues toward improving water quality, on the grounds that maintaining the ecological health of local bays is just as crucial to protecting the character of the community as preserving open space has been.

“We had thought that the protection of land would protect the water, but because of the legacy of different land uses out here, we are still seeing water quality decline,” Mr. Thiele said.

And preservationists celebrate one thing: the apparent continued content of local residents with the CPF program.

“You don’t hear anybody talk about ending it,” Mr. McDonald said. “You don’t hear anybody say we should get rid of it. Everybody knows it’s been good. Everybody who has ever enjoyed a wetland or a park knows what it has done for us.”