Development is progress. Everyone knows that our economy can’t stand still, so we have to grow it.

One would think that we’re talking about plants here, but we’re not. On the East End of Long Island, the goose that laid the golden egg is almost extinct. Ritual sacrifices of buildings and historic sites, based on institutionalized real estate logic, have triggered the demolition of the very places that have not only made this area attractive, but have also contributed to its cultural landscape and history.

Looking back at what has been torn down over the past 10 years, in a random sampling, it becomes very clear that our progressive (no pun intended) zoning laws, coupled with the aforementioned real estate logic, constitute the contributory factors that qualify these structures for entry into the “Demolition Hall of Shame.”

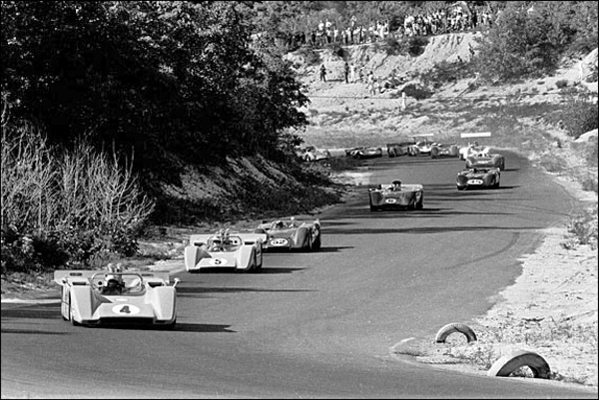

The Bridgehampton Racetrack, built in 1957 with its 2.86-mile track on 550 acres overlooking Noyac Bay, was considered by many in the racing world to be this country’s most challenging track. Paul Newman, Stirling Moss, Richard Petty, A.J. Foyt, Al Unser and Mario Andretti all negotiated the course’s 13 turns and extreme changes in elevation.

Of the track, Mr. Andretti once remarked that it was dangerous and “turn one was an unbelievable corner because it was blind, and you just fell out ... It could scare the bejesus out of anybody.”

The track’s popularity crested in the 1960s and it was not uncommon to have thousands of people flooding the area to visit Bridgehampton, one of the major destinations on the road racing circuit. In later years, other venues supplanted Bridgehampton and the track was used mostly by amateur enthusiasts.

By the end of the 1990s the track fell victim to the now-rescinded Quasi-Public Service Use District (QPSUD) zone, a floating zone in the Southampton Town’s zoning ordinance, which allowed the property to be developed as a golf course, despite protests from Noyac residents concerned about the placement of such a use with pesticides over a sole source aquifer. Golf at the Bridge now sits on the former racetrack site—a site unique to this area and one that could well have been nominated as a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark. Tragically, the last major event held at the racetrack was its own demolition derby.

Of all the grand estates ever built in Southampton, none has had the remarkable and storied history of Bayberry Land. Built for Charles and Pauline Sabin, movers and shakers of the first rank, Bayberry Land had the renowned firm of Cross & Cross as its architects, along with the equally accomplished Marian Coffin as its landscape architect.

For over three decades, the Bayberry Land estate complex was the epicenter of Southampton’s cultural and social crossroads. Built in 1918, the 314-acre Arts-and-Crafts-style estate and its manor house in Sebonac overlooked Peconic Bay and served as the setting for political conventions, fund-raising charities and Davis Cup tennis (Pauline Sabin married Dwight Davis, donor of the Davis cup, after the death of Charles Sabin).

In 2001, television station owner and car leasing magnate Michael Pascucci bought Bayberry Land from the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers for $45 million. He applied for a Planned Development District (PDD) variance (in essence, the successor to the QPSUD zone) to convert the estate to an 18-hole private golf club.

Architects, preservationists and citizens’ organizations were outraged. After three years of public hearings, the variance was granted and the estate was reduced to rubble on May 18, 2004.

The public benefit to mitigate the demolition, derived from the variance agreement, has been slight: access to the course for high school golf practice sessions, a few tournaments open to the public, an archival recordation of the property and a monetary contribution to Southampton Town. None of these measures, however, in any way mitigates the loss of this iconic property to the community.

The initial evaluation from State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) originally stated that the property was of no historic significance. SHPO later changed its tune by saying that Bayberry Land had “marginal” significance after much pressure from Southampton’s Landmarks and Historic District Board.

Bayberry Land will be featured in Ken Burns’s new documentary on prohibition, to be released in 2011. Pauline Sabin, founder of the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform, appeared on the cover of Time Magazine on July 18, 1932 for her efforts to repeal prohibition. Evidently, this award-winning documentary filmmaker views the history of Bayberry Land as having more than just marginal significance.

In 1926, Henry Francis du Pont moved into his 35,000-square-foot Colonial Revival mansion (with 50 rooms) on Meadow Lane in Southampton. The house, furnished with Colonial-era antiques, eventually became part of one of the most important collections of Americana in the United States. Mr. du Pont eventually established the Winterthur Museum in Delaware where many of the holdings from Chestertown house now reside.

Cross & Cross and Ms. Coffin also teamed up to design this house and landscape the property. Ms. Coffin’s naturalistic backdrop of plantings provided a foil for a design that brilliantly minimized the overall scale of the building. By layering the wings of the house from front to back, the Cross brothers created a scenario of a house behind the house, hardly noticed from the street.

After Mr. du Pont’s death in 1969, the house was sold to Baby Jane Holzer (of Andy Warhol fame) and later at a foreclosure auction to coal magnate John Samuels III.

Bought in 1979 by Barry Trupin and renamed “Dragon’s Head,” the house received a renovation with illegal additions that violated the zoning ordinance and turned it into a Gothic version of a chateau from the Loire Valley. The community was enraged by this renovation.

The property was put up for sale and purchased in 1992 by WorldCom director Francesco Galesi. Then in 2003 fashion designer Calvin Klein purchased the property, only to have the building demolished last May.

While many were happy to see this demolition take place with the knowledge that Mr. Klein would be building a much smaller residence, there are others who view the property as demolition by mutilation and that occurred many years ago.

The Moorlands/Windswept property at 477 Halsey Neck Lane and Boyesen Lane—former home of college professor, scholar and novelist Hjalmar Hjorth Boyesen—was illegally demolished on May 6 of this year.

Built in 1893, this charming shingle-era summer cottage appeared before the Southampton Village Board of Historic Preservation and Architectural Review (ARB) in the spring of 2009. The original proposal called for an alteration that would transform the house beyond all recognition. In June 2009, what appeared to be a nice resolution that all parties could accept, the ARB voted to recommend restoration of the house with additions while allowing it to be relocated in the middle of the property.

During this past winter, the boarded-up house was moved to its new foundation. But now, all that is left is part of the first floor alongside all new construction.

This pattern of demolitions, without permits, has been seen over and over again in Southampton Village. The fines imposed on illegal demolitions are minimal when juxtaposed against construction costs. This is simply the cost of doing business.

There are certain behaviors in other situations that are cited as depraved indifference. The situation is analogous here.

To make a mockery of the ARB, to violate the law, and to knowingly understand that whatever penalty is incurred is really just a slap on the wrist speaks to a sense of entitlement that is not acceptable. It’s time for the village and the town to become serious about the heritage they claim to value highly and impose penalties that would prevent these occurrences in the future.

There are so many other lost properties. The Jackson house in Hampton Bays was replaced by a Friendly’s restaurant, courtesy of a PDD variance. Norman Jaffe’s 1985 Raynes House on the ocean in Southampton was demolished in 2003 with little fanfare—except for those who arrived with checkbooks and crowbars and who left with terra-cotta tiles and Tennessee crab orchard stonework in hand after personally extracting and paying for these building parts.

In Amagansett, despite the wonderful intentions of both the realtor and the homeowner, the Barker House, a quintessential mid-century modern beach house by architect Robert Rosenberg, was taken down this spring. The owner of the house (still in the Barker family) wanted only to sell the property to someone who would appreciate it for what it was, someone who would restore rather than demolish. The asking price was even lowered with the hope that the right buyer would appear. Unfortunately, the cost of renovating the small house didn’t make economic sense to most buyers.

Despite the mantra of building smaller, recycling and going green, the public is all for it except when it comes to not having enough space for the accoutrements of 21st-century living. Because there is so little vacant land left on appealing building sites, historic and significant houses are coming down to satisfy a need that can no longer be fulfilled.

So we call all of this progress. And yet the words of Stanislaw Lec still linger in the ear: “Is it progress if a cannibal uses a knife and fork?”