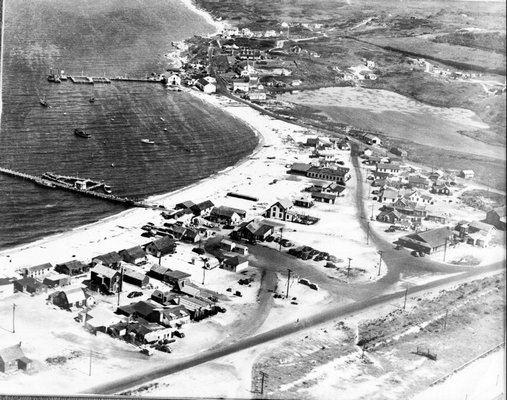

Sitting inside the senior center at the Montauk Playhouse on Saturday, 89-year-old Eugene Beckwith pointed to a framed copy of the old fishing village on Fort Pond Bay.

His family had lived on plot 90, in a small fishing shack that had one bedroom, a pot-belly stove and an outhouse. While his sister slept on a small cot in the kitchen, he slept on the living room couch.

But it was a good life, a close-knit life, that Mr. Beckwith remembers and is eager to reminisce about. And he is adamant that others know about how Montauk’s early fishing village came to be moved made from Fort Pond Bay toward the ocean in the first half of the 20th century. While many attribute that move—both of the modest residences that lined the bay, and the restaurants and post office that served residents—to the Hurricane of 1938, Mr. Beckwith says that the hurricane was merely the first blow.

It was the U.S. Navy that wiped out the village in 1942, Mr. Beckwith said.

Montauk’s early fishing village had its beginnings in the early 1880s when the first fishermen, who came down from Nova Scotia and from Scandinavia, set up shop, so to speak, according to local historian Henry Osmers. When Edwin Baker Tuthill set up his fishing shack and ice house in 1888, the village began to grow. Eventually other fishermen from the Greenport and Southold area came to the Montauk village in season to fish.

The Long Island Rail Road finally reached Montauk in 1895, building a pier into Fort Pond Bay so that fishermen could dump their catch onto cargo cars to be shipped to New York City’s Fulton Market. At that point, Montauk started to become a year-round village, according to Mr. Osmers.

Vincent E. Grimes, another Montauk resident who grew up in the old fishing village, said it was a thriving town.

“There was everything down there: a post office, meat and groceries stores, a barber shop,” he said on Thursday. “Jake Wells had a store and a dock, Perry Duryea and E.B. Tuthill had a small store and a dock,” Mr. Grimes said. “It was a happy place to be. Everybody got along. Everybody was close knit. Every house was close together and everyone played and argued with each other.”

Mr. Beckwith’s father, Eugene Beckwith, and other families like his leased the portable houses for $25 a year. Water was brought to the houses through quarter-inch pipes run by the LIRR, which owned the land. The lease could be revoked at any time, Mr. Beckwith said.

“The houses had to be able to move,” he remembered. “How they could foresee that 15 years later they would have to move...”

During the 1920s, Carl Fisher built his iconic Tudor-style buildings around Montauk, hoping to transform it into the “Miami Beach of the North,” but there was no downtown Montauk as we know it today.

In 1938, the hurricane swept away nine people and also dealt a serious physical blow to Montauk. Certainly it did some real damage to the village on Fort Pond Bay.

It was like “somebody opened the oven door,” according to Mr. Grimes, who was in school with his siblings and Mr. Beckwith. There was no warning.

“It broke windows off houses, and it broke the fin off a windmill and put a hole in its roof,” he said. “All those boats suffered severe damage. Some were put up on dry land after the hurricane and were found a half mile from the water for God sakes. We get a lot of wind out here anyhow. Just because you put up black-checkered flags for hurricanes, nobody knew. It was calm weather until it hit.”

Mr. Beckwith said the schoolchildren were ordered not to look outside while in school because water had crept up and overtaken some homes in the village. Everyone ended up staying at the Montauk Manor for the next few weeks while the Red Cross came in and helped people get back on their feet, Beckwith said.

But the hurricane didn’t wipe out the village. People rebuilt or moved their homes.

It wasn’t until 1942 when the beginning of the end came for little Montauk.

The Navy gave notice to all the residents that they had 30 days to move their homes or move out, because it was going to demolish everything to set up a torpedo testing range.

According to Mr. Beckwith and Mr. Grimes, families were given $250 to $300 to uproot their homes or buy a new one elsewhere.

At that point, Mr. Beckwith was in boot camp for the Navy and not living at home. His parents relocated their home to Myrtle Hollow, between the Montauket Hotel and Duryea’s near Tuthill Road. Mr. Beckwith later sold the house for $13,000.

Other mainstays moved, like the Trail’s End Restaurant, which now sits on Edgemere Street and South Euclid Avenue right near Montauk’s present downtown.

Mr. Grimes’s family had already left the village by that point, but he said he remembers no animosity from the villagers toward the Navy.

“There wasn’t much you could do when the federal government is coming in telling you you’re going to move,” he said. “This was a military zone during World War II. Everything was here—the marines, the Coast Guard, the Air Force, the Signal Corps and the Navy took over everything. It affected everybody, but there was no sense in doing anything about it.”

He said sirens would go off every hour when the torpedo testing was under way and that the Navy would stop boaters to check their identification cards. At certain times in the day, fishermen couldn’t go fishing because of target practice.

Mr. Grimes said at that time, he was living on the ocean side of Montauk and he could see flashes out in the ocean at night.

“U-boats were sinking our cargo ships,” he said. “Thinking back, Jesus, they were right at our doorstep. We’re so far away from everything it is hard to believe anything bad is happening anywhere.”

Mr. Grimes joined the Navy during the Korean War a few years later.

World War II changed the entire dynamic of Montauk, according to Mr. Osmers. Once the Navy built its buildings, “the [old] village then just passed into history.”