Two months after a group called the Tri-Community Working Group called for Sag Harbor to establish a special zoning overlay district to protect the character of the three historically Black beachfront communities of Azurest, Sag Harbor Hills and Ninevah Beach, a longtime proponent of extending the village’s historic district to the three neighborhoods made her case to the Village Board.

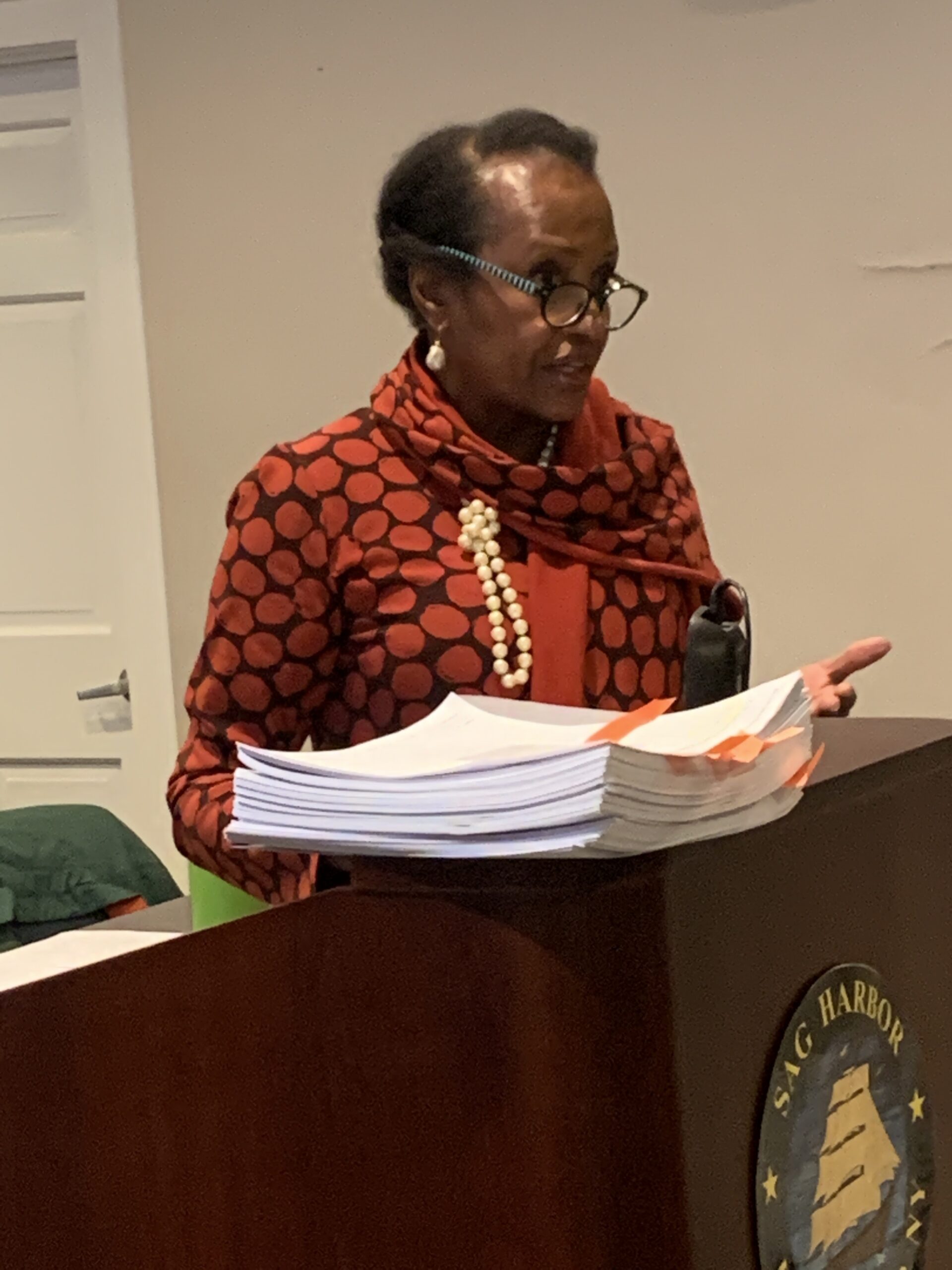

Renee Simons, a resident of Sag Harbor Hills, told the board on Tuesday that designating the three communities, known collectively as SANS, as a historic district would provide more protection than a simple zoning overlay district, which, she said, could be repealed by a future board.

Simons made her comments as the board agreed to schedule a public hearing next month on the overlay proposal, which has been favored by an overwhelming majority of residents in the communities.

She told the board that she and other community members had been working on getting the village to extend the historic district for nearly seven years. The group began its push when low-priced houses in the three neighborhoods were being bought up by developers to be razed or expanded, and longtime residents began to fear that the character of their neighborhoods would be irrevocably damaged.

All three communities were developed in the post-World War II years and provided a place where Black people, who often were denied mortgages or simply prohibited outright from buying property in some areas because of their race, could find summertime respite from life in the city.

The effort to include the communities in the village historic district eventually drew push-back by some residents who feared the restrictions of a historic district would lower property values and prevent homeowners from doing what they wanted with their properties.

But Simons told the board that without historic district protection, the neighborhoods could lose their historic character over time. She pointed out that Sag Harbor once had five Black communities including Chatfield’s Hill and Hillcrest Terrace, but she said that the Hillcrest Terrace property owners association eventually disbanded, and the neighborhood lost its identity.

“This is our moment to codify an important history,” she said, noting that historically Black communities make up a tiny fraction of those protected by historic status across the country. “We have an awesome responsibility to put our thumbprint on it.”

But she added that the neighborhoods are still “evolving and thriving” and would be allowed to do so. “Nobody wants us to remain static,” she said.

Simons said opponents of historic district protection had spread misinformation about what could be done and pointed out that residents would still be allowed to expand their houses and that the village would not be allowed to restrict what kind of renovations could be done inside the home. She stressed that studies have shown that historic designation does not result in lower property values, as some believe. “No one has any data to contradict that,” she said, “just hearsay and belief.”

Although the hearing on the overlay district will not take place until next month, Errol Taylor, president of the Ninevah Beach property owners association, said that Simons did not represent the vast majority of residents in the neighborhood, 95 percent of whom had voted in favor of moving forward with the overlay district proposal.

“We have 300 homeowners,” he said. “We went through pains and worked for a year on this issue, meeting weekly, polling homeowners to come to a proposal that hit what we thought was the sweet spot.”